The Aesthetes were the men and women behind the world’s first youth cult

The Aesthetic Movement is the only British-born art movement to properly influence the whole world in almost every aspect of the arts.

Enormously relevant today, it was the first cultural advance that, almost entirely influenced by foreign arts, crafts, mores and cultures, consciously reacted against the staid Victorian antediluvian age.

A testament to the value of entente cordial, the conceit became known as Stile Liberte in Italy, Art Nouveau in France, the Wiener Secession in Austria, Jugendstil in Germany and Norway and, more appropriately, ??????? or Modern in Russia.

Quite simply, the Aesthetics’ changed the way the world looked and reshaped contemporary culture in every way including music, interiors, wallpaper, paintings, cutlery and even the Paris Metro and New York’s Chrysler Building.

Some say the seed of the ‘movement’ was planted by renowned socialist William Morris who, in 1861, opened a design studio with a gang, in the main, drawn from the Pre Raphaelite Brotherhood, including its founder Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Morris, appalled by the Industrial Revolution that was orchestrated by corporate manufacturing magnates who were rapidly turning Britain into a scarred filthy and artless landscape where every concern (including the worker’s well being) played third fiddle to the financial feeding frenzy. Morris’s intention was to create an arena where beauty, colour and elegant line might thrive and act as a distraction to the filthy smog infested wheezing inner cities.

Of course, Morris was in good company. The Pre Raphaelite Brotherhood had pioneered the aesthetic ideal and rubbed everyone up the wrong way by using their prostitute paramours as models whilst imbibing drugs and strong drink. The first media stars of the embryonic modern world, their mass-produced works were the eras must-have wall hangings while the burgeoning gutter press coverage of their crazy madcap antics sold thousands of copies.

But by 1853 the PRB, even though a spent force, had certainly laid the foundations for the cultural revolution to come by living life to the full and opening their minds to stimulus. As Aesthetic philosopher professor Walter Pater (Oscar Wilde’s mentor) wrote in 1873: ‘Experience itself, is the end. To maintain this ecstasy, is success in life!’ Irrefutably, old Walt had taken a leaf out of French Decadent writers Victor Hugo, Baudelaire and Théophile Gautier who coined the Aesthetic Movement’s mantra ‘Art for Art’s Sake’.

One might argue that the Aesthetics’ were the first post modernists who begged borrowed and filched from everywhere and like Mods and Hippies, were certainly not afraid to embrace global cultural nuance.

Unquestionably, this global trade interaction was really very new. It wasn’t until 1827 that the first ship crossed the Atlantic under steam power and not until later that such voyages to India were regularly made. Consequently, foreign art and exotica was now readily available and travellers returned with tubs of opium and esoteric artefacts, and fired the youth with wild tales of corporeal misadventure.

However, the change that had the most impact on the Aesthetics was the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Amity and Commerce, signed on August 26, 1858. The two countries hadn’t traded for 200 years, so within months, a flood of Japanese culture hit Britain creating a wave of what the French called, Japonism. American painter James McNeill Whistler had seen this first hand in Paris so, when he moved to London in 1859, he brought the ethic with him in exactly the same way that a Mod would return to the UK with a bagful of soul records and a pair of Bass Weejuns.

Whistler encouraged his fellow artists and designers to embrace all things Japanese, their graceful economy of line and simplicity ticking every box that William Morris had laid out. Ipso facto, the Aesthetic Movement was born.

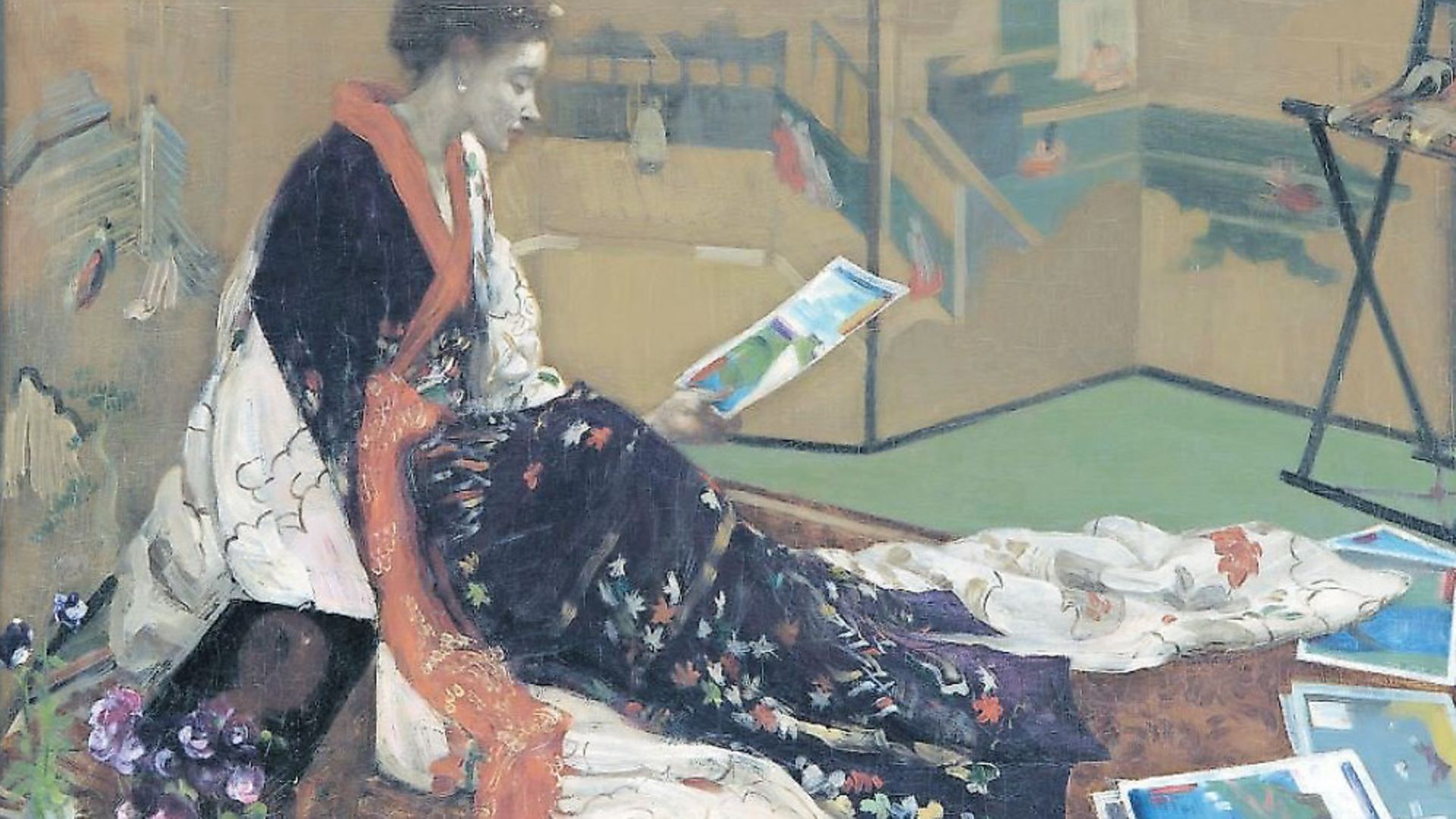

Certainly, Whistler was, with his curling moustache, monocle and the ostentatious attire of a dandy, the Aesthetic Movement’s main man. In 1864, his painting, The Golden Screen, featuring his mistress in kimono in a profoundly Japanese interior, banged his big drum loud. And, just as the Sex Pistols defined the punk milieu with God Save the Queen, so these works delineated the Aesthetic genre.

And, while Whistler pioneered on canvas William Morris reinvented the Victorian interior with his distinctive hand made wallpapers, tapestries and textiles while Liberty – a store that sold British-made arts and crafts; furniture, carpets and foreign curios – became a massive global brand.

Notably, it is via home furnishings that in stepped the most notorious of all our principle characters, the veritable latecomer Oscar Wilde. Describing himself as a ‘Professor of Aesthetics’ he burst onto the capital’s scene in the early 1880s with just one credit as editor of The Woman’s World where he banged on about beds, candlesticks and, last but not least, pillows. Ergo, Whistler greatly derided Wilde as a ‘Johnny come lately’ to the scene and embarked on bitter enmity with the Irishman. In response to a quip of Whistler’s Wilde is alleged to have commented, ‘I wish I had said that’, to which Whistler replied ‘You will, Oscar, you will’.

Undeniably, Wilde and Whistler and the gang were big news. Humourist George Du Maurier created a series of satirical cartoons in Punch, entitled Nincompoopiana that mocked the aesthetes at every turn while Patience by Gilbert and Sullivan ridiculed the Aesthetic Movement’s every affectation.

Accordingly, the old boys in charge who’d fought Napoleon and the Russians, in an effort to keep Johnny ‘racy’ Foreigner and his damned outlandish habits out of the UK, were thoroughly enraged, not only by this intercontinental bartering but also by what was essentially the first ‘youth’ cult’.

Certainly, like jazz, punk and hippy, the scene employed its own, argot and cyphers (the green carnation in the buttonhole – very much a mainstay – suggested bisexuality) and antagonistic manifesto that knowingly rubbed staid Victoriana up the wrong way. Partial to intemperate sexual congress, they also enjoyed the eminently foreign brain-scrunching Absinthe (the fave tipple of Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh and Baudelaire) alongside decidedly exotic imports such as opiates, hashish and cocaine.

Lest we forget, Conan Doyle’s overwhelmingly aesthetic Sherlock Holmes (first published in 1887) loved his Bolivian Marching Powder while the aesthetically inclined dandy, Robert Louis Stevenson completed Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde over a six day nosebag binge in 1884. The Aesthetes were without doubt a rum bunch who was all over these racy continental ways like cheap scent on a pimp.

If that wasn’t enough, the clique, with their dandified, often profligate, fashions stood out like peacocks in a field of grouse. The often emaciated, deathly pale Aesthetic women wore long gossamer gowns and waist length locks while their narcissistic – often rather camp – male counterparts sported long shoulder length locks, extravagant silk cravats, a fine cane to steady their progress and, if spotted in daylight, often adopted the recently available sunglass – a necessity for the racy aesthete who’d contracted syphilis during his dalliances with nymphs of the pave as one of the malady’s symptoms is extreme light sensitivity. Drugs, long hair, sunglasses, crazy mufti and a liberal attitude to sex. It all sounds rather familiar.

But it was Wilde who really got the establishment’s goat. His novel, The Picture of Dorian Grey (1890), encapsulated the aesthetic ethic by exploring themes of decadence, duplicity and beauty while outlining its corrupt and dire consequence. Reviewers vehemently attacked the novel’s homosexual insinuations and dissolution. It was described in the press as ‘poisonous’ and ‘heavy with the mephitic odors of moral and spiritual putrefaction’. It was positively incendiary.

Somewhat spurred on, Wilde seized the chance to explore aesthetic consideration with a larger social commentary and simply turned to theatre and became the most successful playwright of his day. All was going well until he dropped a humongous clanger in 1895 by taking on John Sholto Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry (a prime example of the right wing, high ranking former serviceman who despised everything the Aesthetic Movement represented) who, realising that the Irishman was shtupping his 21 year old overtly camp son, Lord Alfred ‘Bosie’ Douglas, publicly described the aesthete as a ‘sodomite’.

The playwright sued for libel and the Marquess (who was responsible for initiating boxing rules) was arrested. The trial was front page news, Bosie caved, told Queensberry’s lawyers of his and Wilde’s regular sexual liaisons with a bevy of young working class rent boys and the game was up. Thus, the writer was convicted of gross indecency, did two years’ hard labour in Reading Goal and died a broken man in Paris on the November 30, 1900, outliving the Marquees (who appropriately died of a stroke believed to be caused by syphilis) by 10 months.

But even though Wilde scandalised Victorian society he still garnered myriad devotees, such as the young Aubrey Beardsley who, travelled to Paris in 1892 was influenced by the work of Wilde’s friend Toulouse-Lautrec and Japanese woodcuts, returned to London with enough chutzpah to approach Wilde with an offer to illustrate his play Salome (1894). An immediate sensation, Beardsley was catapulted into the upper echelons of the Aesthetic Movement, his simple use of pen and ink, ‘whiplash’ line and block colour marked him as the very first exponent of Art Nouveau – while his drawings featuring enormous genitalia branded him as the most controversial artist of the era. He died of tuberculosis in 1898, aged 25.

Indeed, by the turn of the century, with the exception of the stubborn Whistler, who died in 1903, all the major aesthetes were dead. But their influence lived on: Gustav Klimt, undoubtedly a fan, rose to prominence in 1901; Alphonse Mucha, the undisputed king of Art Nouveau, hit pay dirt after the Exposition Universelle; the American bisexual aesthetic dancer Isadora Duncan came to the fore in 1900 on a tour of Europe; while composers Claude Debussy and Erik Satie, simply by applying the aesthetic conceit to music, made names for themselves after 1905.

The reign of the Aesthetic Movement and its illegitimate heir Art Nouveau ended quite appropriately with the First World War, as new industrial killing machines smashed every consideration bar survival out of the ballpark and a new darker, more cynical and destructive ethic took centre stage.

The party was over and didn’t return till the 1960s when the likes of Granny Takes a Trip proprietors Nigel Waymouth, Sheila Cohen and John Pearse took to selling ‘Aesthetically’ inclined clothing that, embraced by a new Aesthetic Movement that included the Rolling Stones, sparked the hippy movement and influenced a generation anew, who might well have been the great grand children of the form’s original protagonists.

The Aesthetic Movement sucked influence from all over the world and, in turn, inspired the entire globe. Open-minded and progressive, they are an example to us all.

Chris Sullivan wrote for The Face and Loaded and was GQ Style Editor, London correspondent for Italian and L’Uomo Vogue and has contributed to various other publications

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37