Mancunian musician Mark Reeder arrived in Berlin in 1979 and never looked back.

In the four decades since he made the city his home he has managed bands, staged clandestine gigs behind the Iron Curtain, released his own records, remixed countless others, starred in films, presented television shows and somehow found time to run a seminal record label. It is an eventful career which has seen him become a prominent – if cult – figure in his adopted country, while leaving him less well-known in his native one.

That could change with the release of a film which compiles the highlights of his eventful first decade in the city into an immersive production which vividly captures Berlin’s freewheeling spirit in the 1980s, and Reeder’s place at the heart of it.

Equal parts memoir, music doc and social history, B Movie: Lust and Sound in West Berlin 1979-1989 is no ordinary rockumentary. It’s even earned a place on the German educational syllabus.

Propelled along at a rattling pace by a pulsing soundtrack and culled mostly from archive footage seamlessly woven together, it will have you booking the next flight to Berlin while wishing for a time machine. Think Good-Bye to All That meets Trainspotting.

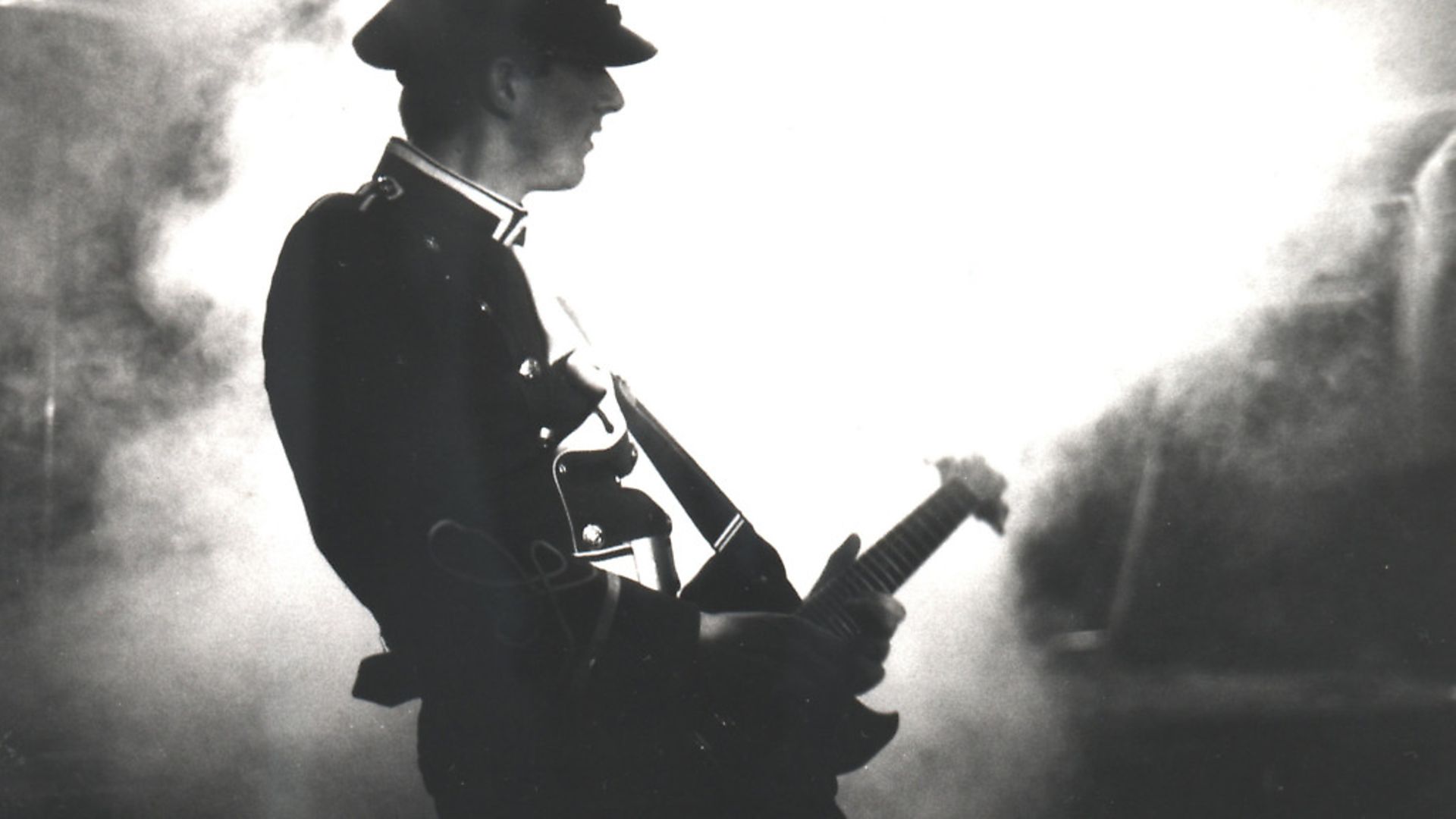

Reeder features prominently himself, cutting a fairly eccentric figure in military garb, taking us behind the scenes of Berlin nightspots and into hairdressers which double as after-dark art galleries, picking through the rubble of a divided city yet to rebuild itself after the ravages of the Second World War, but buzzing with creative energy. He also provides the wry narration, acting as our tour guide with the outsider’s eye.

Reeder was already at the epicentre of Manchester’s music scene during the height of punk, working at Virgin Records and playing in a band called the Frantic Elevators alongside a certain Mick Hucknall. But a love of German imports and a sense of adventure drew him to Berlin.

‘It was such a fascinating city, unlike anywhere I’d ever been. There were no easyJet flights then – Berlin was a 26-hour road trip from Manchester, so nobody knew much about it,’ he says.

At the behest of Tony Wilson, Reeder found himself heading up Factory Records’ German imprint.

According to Reeder: ‘Tony wanted me to be his man in Berlin, but he also wanted me to pay for it.’

Years later Wilson confessed that – in typical fashion from the man who gave the Hacienda nightclub a catalogue number and commissioned record sleeves covered in sandpaper – he thought ‘Factory Berlin’ would look good on headed paper.

The Factory role was mostly a pretext for Reeder to make the city his playground, but he brought Joy Division to Berlin. The band took to the city instantly but the city didn’t return the favour. Only around 100 people saw their one and only Berlin show.

Reeder threw himself into the city’s nightlife. Living in a high-ceilinged squat apartment without proper heating, he gravitated to clubs and bars to simply keep warm, but they were also a gateway to an entire cultural milieu which made all sorts of creative projects possible.

Frequenting legendary clubs like SO36 and Jungle Club, he met arch industrialists Einstürzende Neubauten’s Blixa Bargeld, celebrity junkie Christiane F and Gudrun Gut, frontwoman of all-female electropunk band Malaria! who he ended up managing. He also met filmmaker Joerg Buttgereit, who cast him in splatter film Nekromantik 2, which was mined ingeniously in B Movie.

All of whom you’ll meet in the film, alongside cameos from a diverse cast including the likes of Tilda Swinton, Nena, Keith Haring and yes even, David Hasselhoff.

‘The scene was tiny really, but in these places you’d always met the same people and you just got roped into doing these things. Berlin was like a desert island I’d washed up on and we could just do what we wanted. In a drunken drug-fuelled stupor someone would have some idea and we’d just make it happen,’ he says.

Reeder was originally approached by producer Joerg Hoppe to oversee the film’s soundtrack. After passing over a box of old films to Hoppe, the producer realised what a goldmine he was gifted and Reeder quickly found himself at the centre of the film.

‘I never gave it much thought at the time. I filmed mostly so I could remember what I’d done. With a Super 8 camera you only had two minutes of film anyway, so if the footage was ruined, you just binned it. I didn’t always have my camera with me, so there are many experiences not in the film, like my time in East Germany where I couldn’t film.’

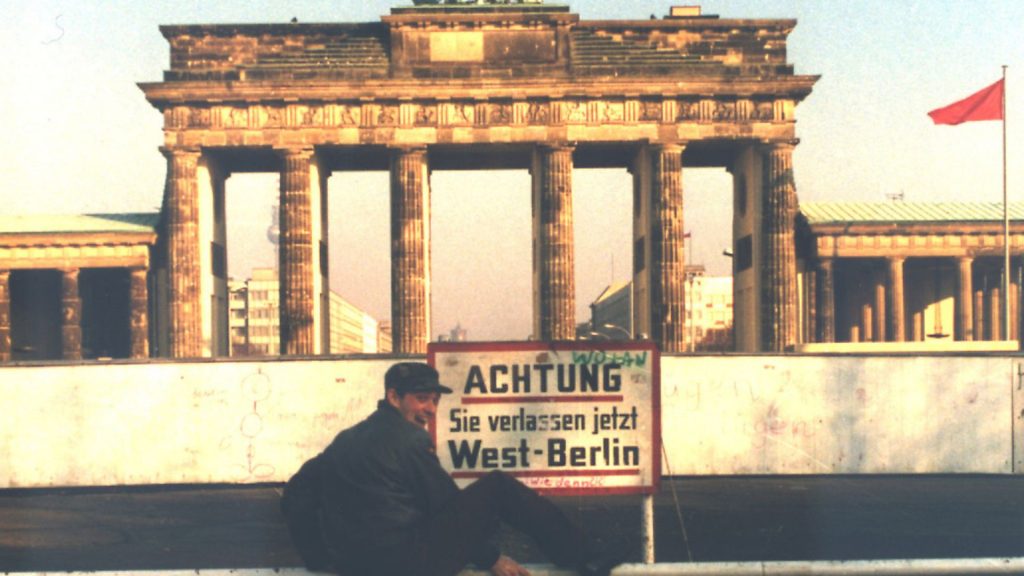

Reeder was deeply fascinated by East Berlin, which he memorably describes in B Movie as ‘Disneyland for depressives’. He made frequent trips across the Wall, often accompanying West Berliners, helping the two sides get to know and understand each other, like some unofficial cultural exchange programme.

‘Getting into East Berlin was too much hassle for Westies. If they went at all it was to sip tea with grandparents or visit concentration camps on school trips. Easties thought that everyone in the West lived this Dynasty life of flash cars, mansion house and designer clothes. But of course it wasn’t like that.’

Music played a central role in these exchanges. Reeder took Dusseldorf band Die Toten Hosen behind the Wall to play an illicit gig in March 1983, the first of many illegal gigs held in East Berlin churches, which took a lot of careful subterfuge.

‘You couldn’t take instruments across the Wall, so we borrowed kit from Eastern bands. The stakes were so high, if we were caught their lives would be upended. The repercussions would be immense.’

One gig was disguised as a benefit for starving Romanians. 600 people came and it was shut down after 45 minutes.

‘It was an act of resistance. East German authorities didn’t believe that punk existed east of the Wall. Punk was seen as a product of the dysfunctional Capitalist West.’

Unsurprisingly Reeder soon got on the Stasi’s radar. He was picked up for a lengthy interrogation at a May Day Parade, and like many Berliners he later discovered some of his friends were informants.

Not that he much cared about the attention. By the end of the 80s, in the dying days of the GDR, Reeder was running trance label MFS. The acronym officially stands for ‘Masterminded for Success’, but was a cheeky nod towards the Stasi’s initials: Ministerium für Staatssicherheit or Ministry for State Security.

The label launched the careers of Paul van Dyk, Cosmic Baby and Alien Nation, laying the foundations for dance music genres which came to dominate the nineties. After years of being in bands, films and TV, Reeder found himself more comfortable behind the scenes.

‘In the nineties I could hide behind the label, so the next film will have less footage of me. It’ll cover the birth of techno and how that underground scene went overground, and became bastardised out of control. Hopefully it will delve into the roots of the music too,’ he says.

B Movie’s sequel, E Movie, is already in the works. Focussing on Berlin from 1989 to 1999, it promises to show how the city ‘went from being an island into an international capital over a decade’.

Reeder’s new album Mauerstadt (meaning ‘walled city’) harks back to Berlin’s history, while also being very much of this time.

He explains: ‘I couldn’t vote in the Brexit referendum so I wanted to address it with this album. The real unification of Germany happened on the dancefloors, that’s where east met west. The future looked so positive after the Cold War ended, nobody cared what you looked like or where you came from. But we’ve reverted back to this wall mentality. With Brexit and Trump’s wall, it’s become about divisions, instead of unity.’

Mauerstadt is an album of collaborations. Contributions from New Order and Inspiral Carpets sit alongside less well-known, international names like Ekkoes and the KVB.

There are always new frontiers and Reeder is just back from touring the film around China.

‘A month earlier the Chinese government decreed that all films depicting, sex, drugs or violence were totally forbidden. I thought, have they done this just to piss me off? That’s most of the film! But the reaction we got was interesting. Even some of the Communist officials enjoyed it.’

Apart from being a fantastic advert for a city captured in an exciting era of colossal change, what can the film teach us today? ‘I’d like the film to inspire people to push boundaries, be daring and just do stuff. Kids think you have to go to a casting show to do anything. But if they see the film maybe they’ll just try something and see what happens.’

The B Movie film, book and soundtrack are available through http://www.b-movie-der-film.de; the Mauerstadt album is available at www.mauerstadt.com

Jools Stone is a freelance travel, music and arts writer based in Brighton.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37