Melburnians have a long history of outspokenness. The 1854 Eureka Rebellion of miners which led to an expansion of the electorate, the 1856 stonemasons’ march on parliament which resulted in the eight-hour day, and even the last stand of Ned Kelly, symbolic of defiance of the colonial authorities, are foundational events of the city’s history.

This is a place where freedom has been important and, as a place where music is an equally valued concept – Melbourne has more live music venues per capita than any other city in the world – the city’s boundary-pushing artists have been synonymous with creative freedom.

The post-punk of The Boys Next Door, which morphed into the gothic rock of The Birthday Party and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, came out of the city in the 1980s, while the ‘Little Band’ scene, revolving around legendary venues like the Crystal Ballroom and The Tote, produced the dark aural experiments of Dead Can Dance.

But Dead Can Dance’s extraordinary vocalist Lisa Gerrard was a rare prominent female on this scene, and when you add the dad rock of Crowded House (Four Seasons in One Day [1992] referenced the famously changeable Melbourne climate), and Men at Work, with their laddish alternative Australian national anthem, Down Under (1981), Melbourne’s music could be seen as a rather masculine affair.

In fact, the city has produced a stream of female artists who have defied expectations of them – both as women and as Australians – to achieve record-breaking success.

The first was Dame Nellie Melba, born in the city in 1861 as Helen Porter Mitchell, but later taking the diminutive form of her home city as her stage name.

Initial musical training and performances in Melbourne proved her talent, but paternal disapproval of a woman singing in public and the whims of an abusive husband threatened to thwart her musical ambitions.

Regardless, Melba went to London in 1886, aged just 25, and with a three-year-old son in tow. She soon became the most celebrated soprano in Europe, amassing a huge personal fortune, and her 1902 homecoming performances at the Melbourne Town Hall and the grand Princess Theatre were some of the most celebrated cultural events in the city’s history.

Some six decades on, another Melburnian woman would also defy a failed marriage and the restrictive expectations of motherhood to make it big abroad. Helen Reddy, who died last week, first appeared onstage aged four as part of a family vaudeville act, but she rebelled against the showbusiness life and married an older man in 1961, at the age of just 20, and had a child.

When that relationship failed Reddy found performing was in fact in her blood, and she won a 1966 TV talent show prize of a trip to New York to record with Mercury. She upped sticks and left, taking her three-year-old daughter with her. In America she found a new, supportive husband, but little enthusiasm from the music industry for a new female artist. But although success wasn’t instant, when it came it was stellar.

It was the B-side to 1971’s I Believe in Music that launched Reddy – a version of I Don’t Know How to Love Him from Jesus Christ Superstar that became a hit in its own right. But it was the following year’s I Am Woman (1972), co-written by Reddy with Sydney songwriter Ray Burton, that really made her name. Opening “I am woman, hear me roar/ In numbers too big to ignore” it captured the spirit of second wave feminism in the immediate aftermath of The Female Eunuch (1970), the launch of Ms. magazine, and the founding of academic journals like Feminist Studies.

I Am Woman went to No.2 in Australia and made Reddy the first Australian-born artist to top the Billboard Hot 100 and to win a Grammy – Reddy thanked God in her acceptance speech, “because She makes everything possible”. Despite British success being limited to 1975 No. 5 single Angie Baby, a twisted tale of teenage madness,

Reddy was the biggest selling female act in the world in 1973 and 1974.

Her determination to succeed gave her a platform not just to champion women in her songs, but also to support other female artists. When Olivia Newton-John made her career-crucial move to the US in the mid-1970s, it was at Reddy’s urging. The British-born Newton-John lived in Melbourne from the age of six and, like Reddy, she rebelled against her background, pursuing showbusiness instead of the academic path of her linguist father.

At just 16 Newton-John got the same break as Reddy – winning a talent competition prize of a foreign trip, this time to Britain. This was the year when Melbourne folk-pop outfit The Seekers were already achieving UK chart success, but Newton-John’s raw-edged debut on Decca, Till You Say You’ll Be Mine (1966), couldn’t replicate that success.

It was a Dylan cover, If Not For You, that saw Newton-John’s 1971 breakthrough in both Australia and the UK. The song was produced by Newton-John’s one-time fiancé, the Shadows’ Bruce Welch, and fellow Melburnian John Farrar. Farrar, by then also a member of the Shadows, would write the three US No.1s that followed Newton-John’s first, 1974’s saccharine I Honestly Love You, as well as Hopelessly Devoted to You (1978), and he produced the singer’s final stateside chart-topper, the image-transforming Physical (1981).

Like Reddy, who was dismissed as “the queen of housewife rock”, Newton-John’s apparent mildness has obscured the grit it took to obtain her record-breaking success, and as a campaigner on breast cancer and founder of a research hospital in Melbourne, she’s been a champion for women.

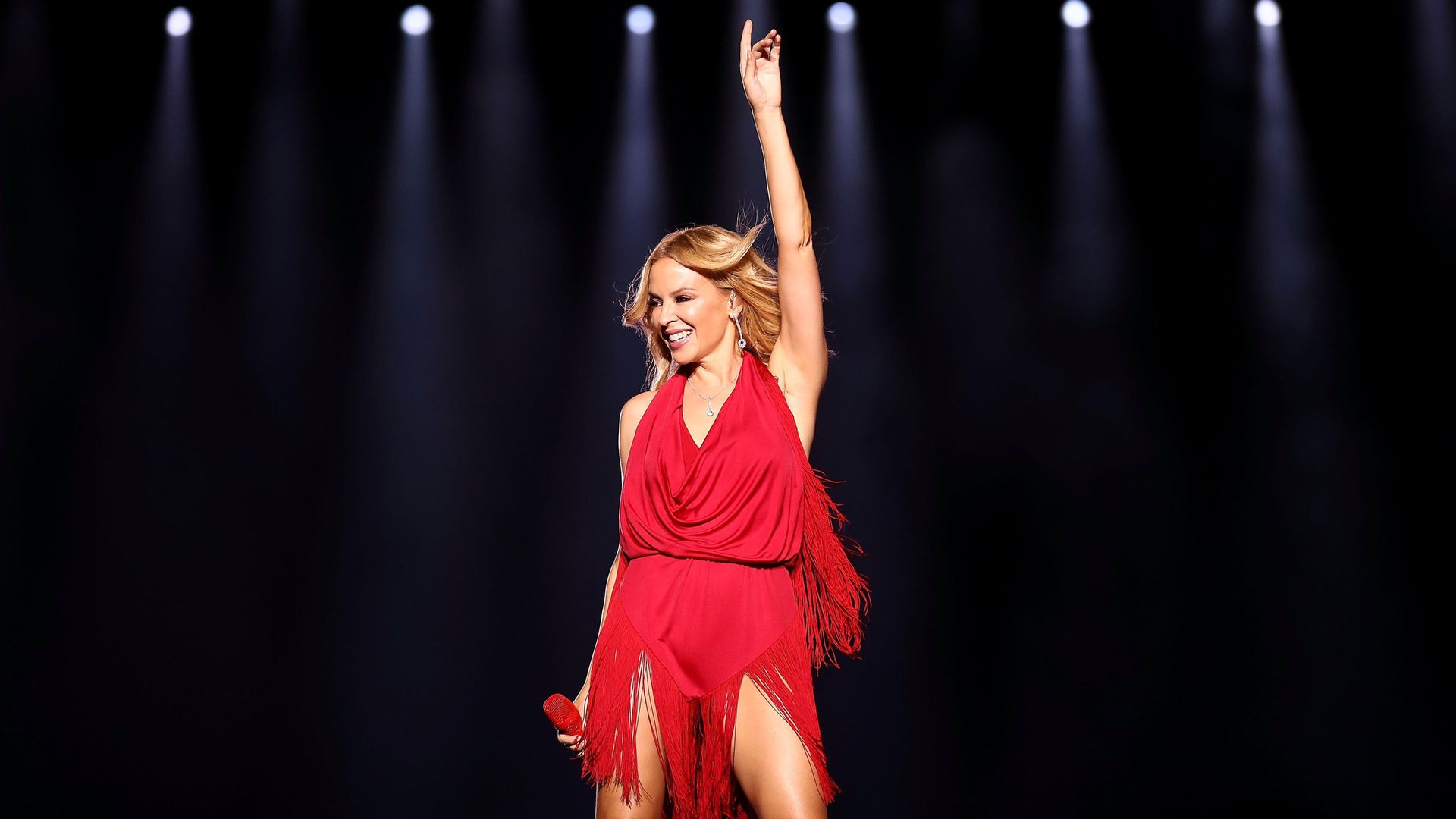

The biggest-selling Australian artist of all time came from humble beginnings in Melbourne’s eastern suburb of Surrey Hills, going on to become so famous she is known mononymously as just ‘Kylie’.

Kylie Minogue’s Welsh mother was a trained dancer but worked as a hospital tea lady to make ends meet, and the stage provided a route to a less humdrum existence for the young Kylie. After early appearances in Melbourne-produced dramas like The Sullivans, her Neighbours role came in 1986 and a signing to Melbourne-based Mushroom Records led to her debut single, the following year’s cover of Little Eva’s Locomotion.

It would become the highest-selling single of the decade in Australia, but Stock, Aitken and Waterman made a completely different version for release on the UK market after Minogue began working with them and had a UK No.1 with I Should Be So Lucky (1987).

The same year’s follow up, Got To Be Certain, with a video filmed in multiple locations around Melbourne, had reached No.2. The pop svengalis would direct her career for the next four albums. But while it seemed pop success was easy for Kylie, she has rarely taken the easy route.

In 1993, Kylie jumped ship from the Stock, Aitken and Waterman machine and signed to independent label deConstruction. The brooding Confide in Me (1994) was her own Physical moment – a deliberate move towards a sexier, more grown-up pop – and collaboration with the Manic Street Preachers for 1997’s Impossible Princess followed.

Kylie’s Come into My World (2001) video directed by Michel Gondry, shoot with Marilyn Monroe photographer Bert Stern for Vogue Australia in 1994, and Dolce and Gabbana-designed costumes for her Aphrodite: Les Folies Tour of 2011 are the kind of projects that have placed her at the intersection of pop culture and art, a relationship explored in a 2007 exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, while the Melbourne Arts Centre preserves her Spinning Around (2000) gold hotpants and Can’t Get You Out of My Head (2001) white hooded jumpsuit in their permanent collection. While Kylie has stopped short of an avowed feminism, she had proven she is rather more than a mere ‘pop princess’.

The two worlds of Melbourne’s music clashed in surely one of the most unlikely pop singles ever, Nick Cave and Kylie Minogue’s Where the Wild Roses Grow, in 1995. It was both evidence of the continuing difficult position of women in music – Minogue’s chance to stand in the reflected glory of Cave’s coolness came at the cost of being cast as a victim in a murder ballad – and that Melbourne’s music always defies expectations.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37