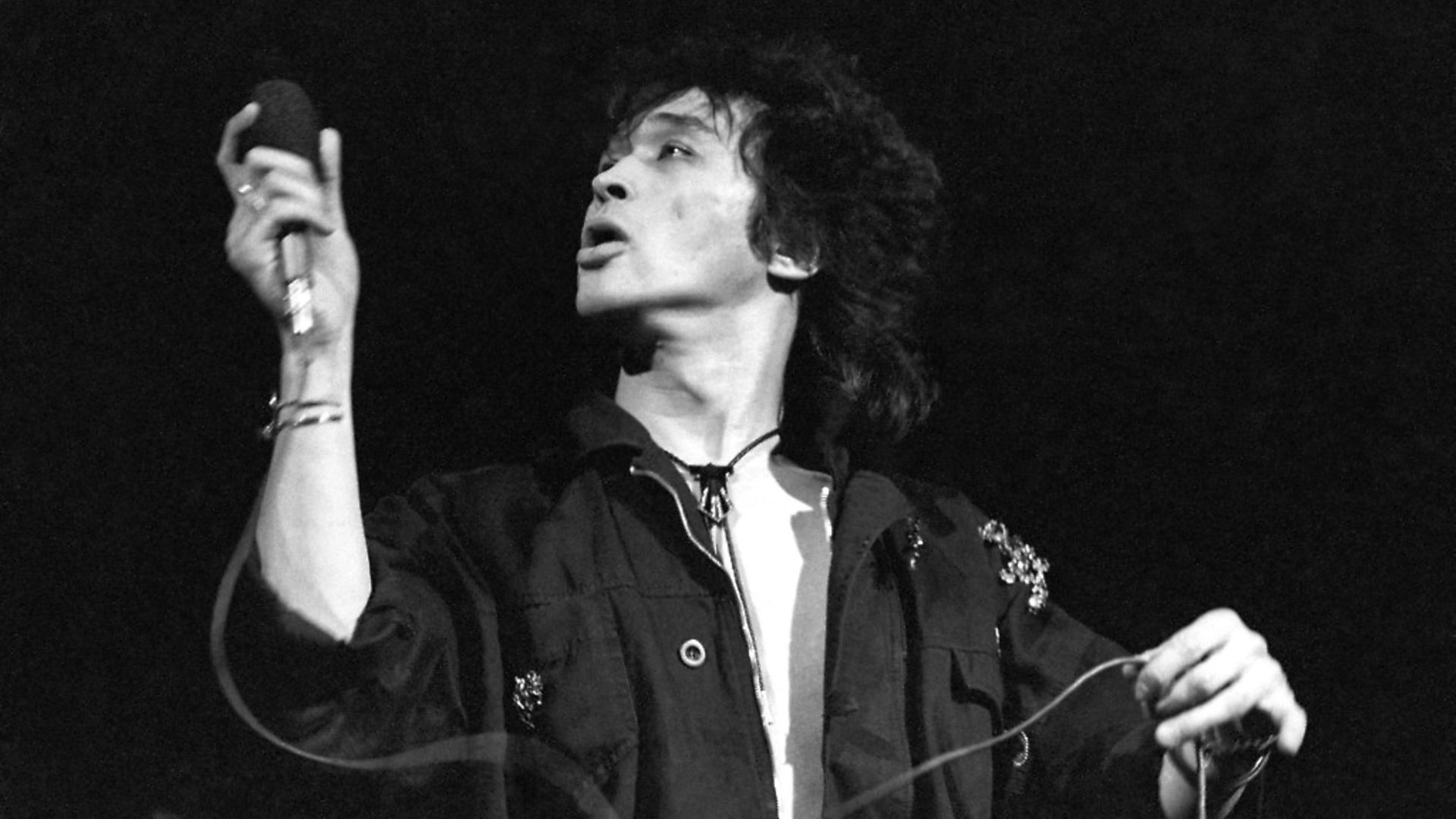

CHARLIE CONNELLY looks back at the life of Soviet and Russian singer and songwriter, Viktor Tsoi.

During an interview in November 2012 Mikhail Gorbachev recalled the moment in 1985 when, on the death of his predecessor Konstantin Chernenko, he became leader of the Soviet Union: ‘The cardiologist telephoned me and said, ‘Mikhail Sergeevich, Konstantin Ustinovich has passed away’. The first thing I did was appoint a Politburo and convene a meeting, at which I turned to the foreign minister Gromyko and said things needed to be done differently. Tsoi is singing ‘We want changes’ in concerts, I said, and people are saying openly and directly, ‘We want changes’.’

Konstantin Chernenko died on March 10, 1985. Viktor Tsoi’s song Khochu Peremen (‘We Want Changes’) was first performed in public by his band Kino during the summer of 1986. So profound was the song’s influence on perestroika-era Russia, so deeply did it resound in the hearts of the Russian people, even the man who devised perestroika found himself projecting Tsoi’s lyrics onto his own recollected experience.

With its urgent drum-beat and sub-rockabilly riffs beneath Tsoi’s impassioned call for change – ‘Our hearts need changes, our eyes need changes, into our laugh and our tears, and into our pulse and veins. Changes! We are waiting for change’ – Khochu Peremen remains an anthem for the dispossessed across the former Soviet Union.

During the attempted coup in 1991 the song blasted out of speakers at the barricades. Two years later it was playing during the constitutional crisis that saw Boris Yeltsin attempting to disband the Supreme Soviet. In Belarus in 2011 it was the soundtrack to protests against the autocratic president Alexander Lukashenko and three years after that it thundered out during the Euromaidan demonstrations in Ukraine.

Yet Viktor Tsoi, the charismatic lead singer of Kino and the composer of Khochu Peremen, never saw it as an overtly political song. As his friend and bandmate Aleksei Rybin explained after Tsoi’s death, ‘The changes Viktor was singing about were not simply changes to the political system,’ he said. ‘He was singing about a more profound kind of change, change within the person.’

Thirty years after his death at the age of 28, Viktor Tsoi remains a huge figure in the former USSR. There’s a museum dedicated to him in the St Petersburg boiler room where he worked, while a wall off Arbat Street in the historic centre of Moscow remains covered in ever-changing tributes to the singer. Away from politics, in 2018 researchers at the University of Tyumen in Siberia discovered a new species of oribatid mite on the forest floors of Malaysia. They named it Trachyoribates viktortsoii.

For all this posthumous feting on top of the success he experienced in his lifetime Tsoi never knew the material trappings of rock star life. It was only in his last couple of years, when Gorbachev’s reforms allowed artists like Tsoi out of the cultural shadows, that he could even appreciate the widespread nature of his fame. Having spent most of his career playing illicit gigs in small venues and house parties, in June 1990 Tsoi led Kino onto the stage in front of 62,000 people at the Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow, closing the show with a joyous singalong rendition of Khochu Peremen that all but tore the roof off the place.

Even then he lived modestly with none of the hedonistic excess you might expect from an icon of disaffected youth. Even his early death wasn’t quite in the rock ‘n’ roll tradition. Less than two months after that triumphant show at the Luzhniki Tsoi was driving back from a fishing trip in Latvia in his boxy, noisy, five-door Moskovitch Aleko when it crossed the central reservation and ploughed headlong into a bus coming in the other direction, killing him instantly. There were no drugs or alcohol in his system; he’d simply nodded off at the wheel.

You didn’t get into rock ‘n’ roll in the Soviet Union to get rich. If bland, state-approved pop based on old Russian folk songs wasn’t your thing you tended to gravitate towards the underground scene where albums were recorded in apartments on rudimentary tape recorders and a few copies made that were passed around samizdat-style; listen, enjoy, pass it on. Gigs were low key, often no more than informal jams in someone’s apartment. Albums would be smuggled in from abroad and mined for influences, glimpses of a far-off youth culture that seemed to be from another planet. Even at his creative peak in the mid-1980s Tsoi had to fit Kino around his job as a boilerman in an apartment block. When he sang of the hopes, dreams and travails of the working Russian he knew exactly what he was talking about: his songs resonated because they had the authenticity of experience.

‘Tsoi means more to the young people of our nation than any politician, celebrity or writer,’ said Komsomolskaya Pravda, the newspaper of the Soviet Communist Party youth movement, breaking the news of his death. ‘This is because Tsoi never lied and never sold out.’

He was born in Leningrad to Valentina, a PE teacher, and Robert Tsoi, an engineer whose family came from what is now North Korea. After a chequered schooling in which he excelled at art but was expelled from his college he studied wood carving and wrote songs. By the turn of the 1980s Tsoi was on the fringes of Leningrad’s underground rock scene, playing bass for a band called Palata No. 6 and forming the close friendship with Aleksei Rybin from the band Piligrimy that would later lay the foundations of Kino, the greatest rock band in the history of the USSR.

The pair first collaborated as members of punk outfit Avtomaticheskie Udovletvoriteli (the Automatic Satisfiers), whose riotous gigs attracted the attention of Boris Grebenshchikov. Grebenshchikov, leader of the pioneering band Aquarium, is still widely regarded as the father of Soviet rock ‘n’ roll and his patronage was a boost to many artists on the unofficial Soviet scene. Even amid the howling racket made by Avtomaticheskie Udovletvoriteli Grebenshchikov could hear the quality of Tsoi’s songwriting and took him under his wing. In the summer of 1981 Tsoi and Rybin were gigging as Garin i Giperboloidy with drummer Oleg Valinksy. The new outfit was admitted to the prestigious Leningrad Rock Club, an establishment connected to Grebenshchikov that was semi-tolerated by officialdom but whose gigs were riddled with the KGB. When Valinsky was conscripted into the army the remaining duo became Kino, the Russian word for cinema. It was, thought Tsoi, easy to remember, easy to pronounce and would look big on posters.

Tsoi wrote constantly and before long had enough material for the band’s debut album, 1982’s 45, named because it was 45 minutes long and enough to fill one side of a cassette tape. With the help of Grebenshchikov, who loaned members of Aquarium for the recording, on 45 Tsoi demonstrated his willingness to tackle political issues albeit in a necessarily oblique, veiled manner. In Elektrichka for example, named after the commuter chuggers that served big Russian cities, Tsoi describes a man sitting on a train that’s taking him somewhere he doesn’t want to go but he’s no choice other than to stay on board.

Four more albums followed in four years, each increasing the band’s reputation across the Soviet Union, but it was their 1988 album Grupa Kruvi (‘Blood Group’) that would establish Kino as Russia’s leading band and Tsoi as the voice of a generation. The album coincided with Gorbachev’s reforms, allowing Tsoi to be more overt in the lyrics he was writing. The title track, for example, was critical of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan but sympathised with the plight of conscripts sent to the region.

By then the charismatic frontman was also a film star. In the final scene of Sergei Solovyov’s 1987 cult thriller Assa Tsoi is slumped in a chair while a restaurant manager reads out a long list of regulations by which Tsoi’s band have to abide to play for the diners. She’s still in full bureaucratic flow when he stands up, walks out and heads for the dining room, shot from behind.

The rest of Kino are on stage playing the intro to Khochu Premen and Tsoi climbs onto the stage and begins to sing, eyes screwed shut, body tense as he wrings every ounce of authenticity from his slight frame. The camera moves around behind him to reveal not an expanse of empty tables and chairs but a huge packed crowd, holding up cigarette lighters and singing along, calling for the coming changes that the man who inspired them would not live to see.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37