MPs should stop being so timid, they have a duty to seek a reverse of direction, whatever happened in June’s referendum, says Steve Richards

https://twitter.com/TheNewEuropean/status/787005271688306688?lang=en

What is astonishing is not how little we know about what Brexit will mean but how much. What we know is bleak.

Already we have discovered how market sensitive the issue is. The value of the pound plummets more or less every time Theresa May utters a word on the issue. After her two speeches at the Conservative Party conference it was falling so fast even some of the robustly optimistic Brexit ministers were taken aback. I suspect she was too. Here was the verdict of international markets before she has said very much of substance.

Away from the UK leaders, we discover speedily the rest of the EU are indicating they are not going to take Brexit lying down. Why should they? There are opportunities for them, as well as risks, in the turmoil generated by the UK referendum. Once Article 50 is triggered they will hold most of the cards and determine the structure of the negotiation that will follow. That is the deal with Article 50. The country seeking to leave has the power to determine the timing. The rest of the EU determines then the manner of the departure.

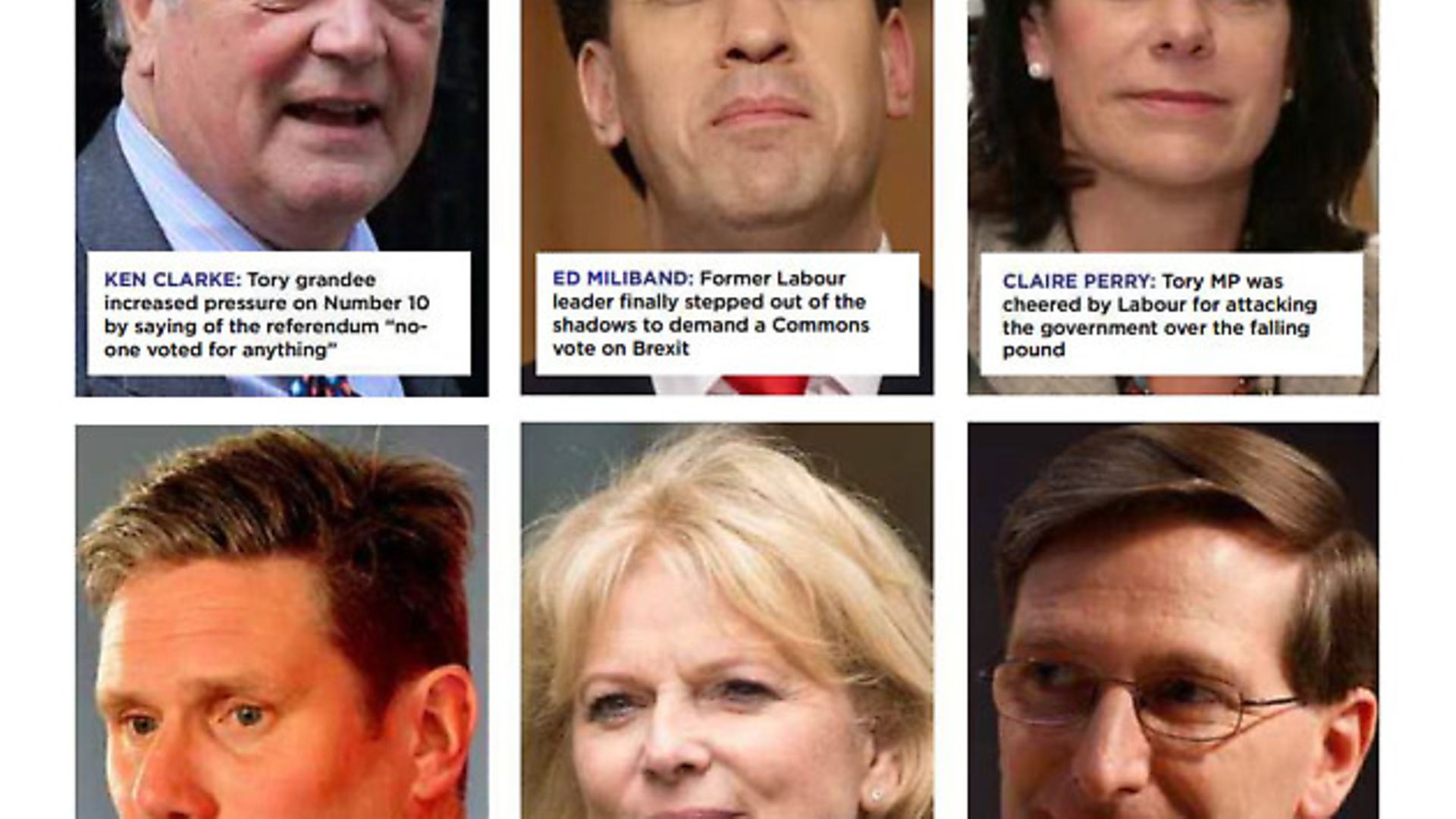

Contrary to the wishes of the Prime Minister we know there will be a running commentary on Brexit because one way or another relevant ministers will be summoned to the Commons to explain what is happening. On Wednesday, the issue dominated Prime Minister’s Questions and a long debate followed afterwards. This is good for UK democracy and will prove a nightmare for a government that had hoped naively it would be able to hold its negotiating hand close to its chest.

We also know that May has been forced to disown various statements made by her key Brexit ministers in these early months, with Number Ten suggesting they were expressing personal views rather than those of the government. What is more, the Treasury is already in a different place from May and her Brexit ministers. When the mild mannered Chancellor Philip Hammond suggested at the Tory conference that no one had voted in the referendum to be worse off, he was signalling a polite internal revolt. For him the economy is the priority. How unsurprising that an internal government paper warning that a hard Brexit could cost the UK £66 billion was leaked before some ministers had even read it.

All these eruptions occur when virtually nothing has happened. The UK is still in the EU. Article 50 has not been triggered. The formal negotiations have not begun.

We have some clarity also as to how long the process will last. The long timescale is bleak too. May stated the obvious when she announced that EU laws and regulations would be transferred to the UK parliament after Brexit in 2019. There is no time between now and then to contemplate revisions to that mountain of legislation. In proclaiming her move at the Conservative conference she was making the most of a logistical inevitability. Even so the clarification is illuminating. The transfer of laws and regulations will take place in 2019. The next general election in the UK is scheduled for 2020. The pre-election campaign will already be underway and that will mean near legislative paralysis at Westminster until the election is over. Changes to EU laws and regulations will therefore take place during the parliament elected in 2020. The revisions will dominate that parliament which is due to last until 2025. This part of Brexit, not necessarily the most complex, will not reach resolution for another nine years at the earliest.

May has also made clear that controlling immigration is a red line in her negotiations and that the UK will not accept the jurisdiction of the European court. This means the UK is out of the single market, seeking vaguely defined ‘access’. More than that of any other EU member, the UK economy is dependent on financial services. Financial services in the UK get a good deal in the single market. At the very least the deal is under threat. Ministers speak of ‘rebalancing’ the UK economy. So did their Labour predecessors after the 2008 crash. This is an admirable objective but one that is proving elusive. In the meantime financial services continue to be pivotal to the prospects of the UK economy. As far as they plan for the near future it is with doubts about what will happen next.

Many MPs agree that the vast amount we already know is alarming. A majority of them supported Remain. Given the turbulence caused by Brexit during May’s otherwise authoritative and assured political honeymoon, those I speak to are more convinced than ever they were right in their pre-referendum convictions. With good cause they demand that parliament should have a say in what form Brexit takes. But nearly all of them add that of course they accept the outcome of the referendum and the UK will be leaving the EU. Most MPs demanding a vote when the government seeks to trigger Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty add that they would vote in favour in light of the referendum result.

They recognise a potential disaster and yet risk being agents that help to bring the disaster about.

They are being too timid. They need to battle very hard for, at the very least, a so-called soft Brexit in which the UK remains a full member of the single market. They should be prepared to scupper the entire Brexit project. And with majorities in both Houses have the power to do so.

Their reluctance is understandable. How can they act against the verdict of the voters? Will they not be punished electorally for doing so? Will they trigger a near insurrectionary mood amongst those who voted ‘out’? Will such an act destroy the political party they represent?

The answers to these questions should cause only limited agonising. If MPs sense that the UK is moving towards the cliff’s edge they have a duty to seek a reverse of direction, whatever happened in June’s referendum. Voters will not become insurrectionary when they realise how much worse off they will be under Brexit. All the major parties are in crisis anyway so future acts of defiance will not be the cause of their doom.

The Conservatives are already suffering tensions over Brexit. Soon the internal splits will be explosive, as they were over the much simpler Maastricht Treaty in the 1990s. Labour is already split and in an eternal circuitous crisis with a leader adored by most members and viewed with fuming disdain by MPs. The Liberal Democrats were virtually wiped out as a parliamentary force. The SNP can act with confidence in opposing Brexit knowing it speaks for a majority of voters in Scotland, an important element of the crisis to come.

Contrary to the assumptions of ministers at Westminster, Nicola Sturgeon is deadly serious when she raises the possibility of a referendum on independence. Those close to the First Minister point out the opportunity will never be more propitious, Brexit and the collapse of the Labour party in Scotland.

Historians often look back at catastrophic events and wonder why those in a position of power did not do more to prevent them from taking place when the looming calamities were obvious in advance. What has happened before Article 50 is triggered shows that Brexit scares markets, causes political turbulence, will go on for at least a decade when there are more important matters to be decided on, makes managing a government even more nightmarish than usual. This early phase is a mere tip toe on the dance floor.

Will historians look back and ask the deadly question again – why did no one stop an obvious impending disaster? In the case of Brexit nothing irreversible has happened yet. MPs and peers can and must stop the historians’ question being posed.

Steve Richards is a political writer and broadcaster; follow him at @steverichards14

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37