MIC WRIGHT finds plenty to ponder in a new exhibition exploring the complex world of addiction, even if it has less to say about more modern vices.

I’m watching a video of a young man with a cigarette in his mouth. It’s in extreme close-up. He blows smoke rings. They drift out of his mouth and then back in again. This is a 20-year-old artwork in a brand new space: Richard Billingham’s Tony Smoking Backwards now part of Hooked, the first exhibition at the Science Gallery London, at King’s College London, which looks into the complex world of addiction.

Tony Smoking Backwards was a contemporary artwork then but now it feels like a relic, made in 1998, nine years before the smoking ban took effect, a moment in culture that the Daily Telegraph lamented as ‘the end of Britain as a libertarian nation’. The right to get lung cancer is, of course, part of our unwritten constitution.

The catalogue text for Billingham’s video installation describes it as an exploration of ‘the relationship between boredom and addiction’. The movement of the smoke rings is fascinating. It’s easy to find yourself standing watching them for a long time. But as I do, I don’t find myself thinking about addiction.

Instead, the looping footage becomes almost abstract. It’s a sense I had throughout Hooked. Making art about addiction is difficult because addiction is a visceral thing for both the addict and those around them. On the whole, the works in the exhibition feel like intellectual commentary upon a phenomenon, holding the reality of it at arms length.

Hooked explores addictions of all kinds – from food to sex to drugs and alcohol. When I entered the upstairs gallery, I had to step around the remnants of the latest version of Sugar Rush, a table made of sugar conceived by the design studio Atelier 010 and produced in new editions in the gallery space. The intent is to make you think about ‘our consumer-driven society’ and witnessing the table disintegrating might well do that. Looking at the aftermath, strewn teacups and dissolving sugar, left me craving a chocolate digestive and a cup of tea (no sugars).

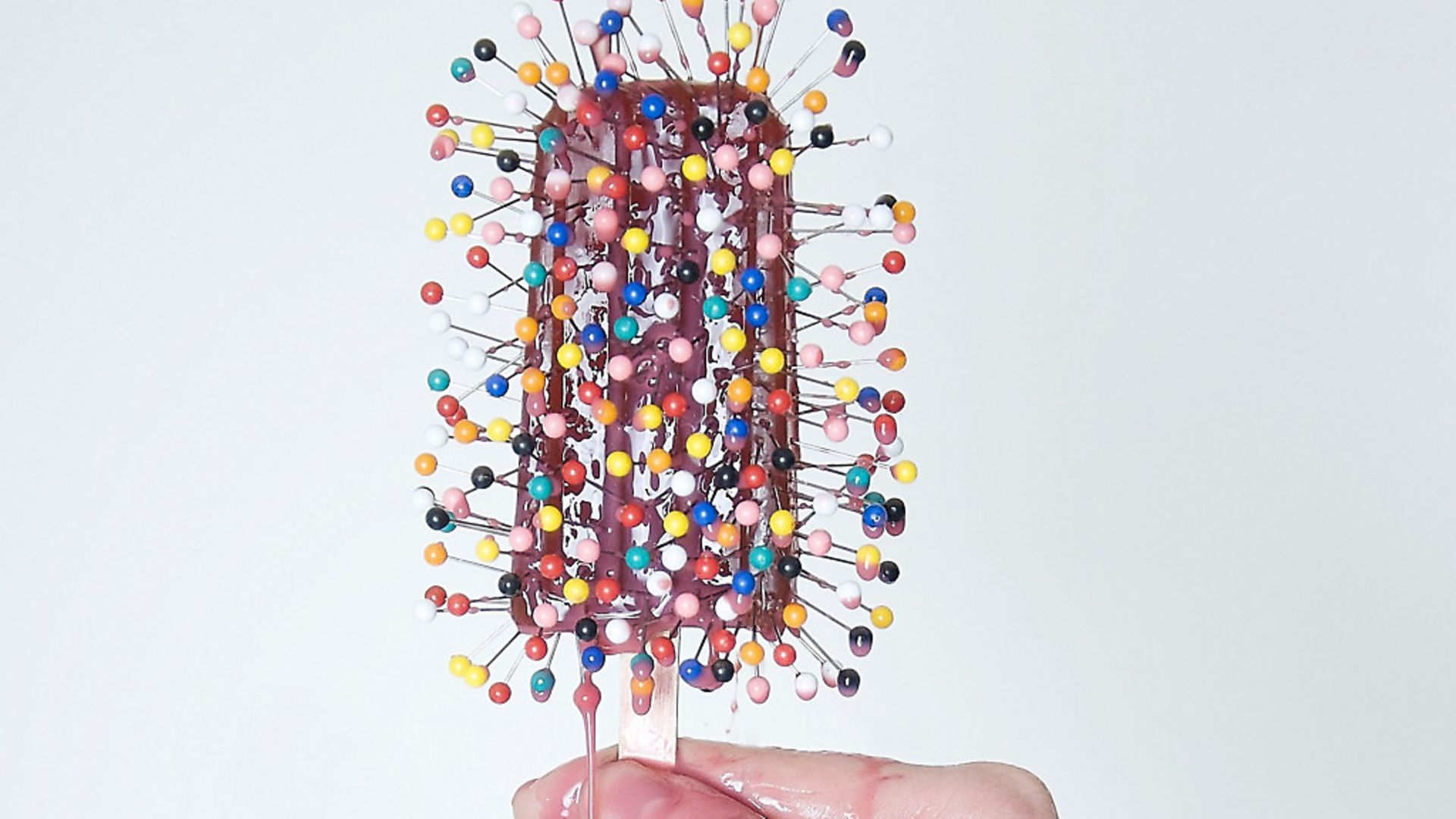

Another Day on Earth (Pin Cushion) by the young American photographer, Olivia Locher, is more arresting: A hand holds a melting chocolate lolly covered in brightly coloured pushpins, like a culinary invocation of St Anthony shot through with arrows. The image, which features prominently in the exhibition’s publicity material, makes a sharp point – pun intended – about the interlocking relationship between addiction’s cravings and the suffering provoked by giving in to them.

A second image from the series, Another Day on Earth (Marshmallow Pants), is also featured, though its vision of a woman wearing tights stuffed with the confectionary feels decidedly more comic rather than some kind of indictment of our uncomfortable relationship with processed food.

Where Hooked touches on newer addictions – to the internet, social networks and smartphones – it’s least effective. Sisyphus, a multi-screen video installation by Esmeralda Kosmatopoulos, is a set of brightly-coloured battery indicators shown rising and falling. While it evokes our reliance on the devices in our pockets, it can’t match the ridiculous real life dread of seeing your smartphone battery drop into the red zone. Please Don’t Like This! by Jonah Brucker-Cohen feels similarly glib. Described as ‘an experiment in how we perceive and act on social media voting’, it is a web page featuring a Facebook ‘Like’ button and text that entreats the viewer not to press it. That humans will push buttons they’re told not to doesn’t feel revelatory, particularly to anyone who’s seen Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

The Abyss by Fabio Lattanzi Antinori is the most effective of the exhibits focused on the online world: A shiny black polyhedron on a stand, its screen displays phrases used to sell cheap goods on eBay and Amazon combined with pleasing synonyms and the most-used adjectives from the past 20 years of advertising in sharp red text. Severed from the objects they were describing, the couplets become like commercial prayers, more desperate in their attempts to persuade with no visuals to support them. That the sculpture itself is so luxurious while displaying words previously tied to cheap objects only enhances the effect.

Still, it is the personal testimony about addiction that is most likely to stay with you when you leave Hooked. Melanie Manchot’s Twelve is another video installation, featuring 12 people from Liverpool, Oxford and London, who were in recovery from substance abuse, who contributed their personal written and oral testimonies to the work. While Manchot injects a layer of artifice into the process, referencing scenes from films by directors such as Gus Van Sant and Michael Haneke, it’s the exhibition’s most direct expression of what addiction and recovery actually involve.

It is perhaps unsurprising that the artistic responses to drug and alcohol addiction are the most powerful in Hooked and that those that try to explore more modern compulsions are the least. While it’s easier for the media to get exorcised about more novel folk demons – children addicted to playing Fortnite or adults pushing their families into penury through online gambling – online and technological addictions can feel very flat when they’re tackled by art. The smartphone era only properly began in 2007, when Steve Jobs unveiled the iPhone, and in the 11 years since, handwringing about the hold the technology in our hands has over us already feels a little passé. It’s why Daniel Mallory Ortberg was able to memorably dismiss Charlie Brooker’s techno-dystopian horror series, Black Mirror, as ‘what if phones, but too much?’

There’s a sense that while academics and policymakers are still struggling with the implications of the smartphone and ubiquitous internet connections, for most, reliance on those technology feels mundane. We’re almost waiting for the next addiction: Kids lost to this reality and yolked to their VR headsets, a new breed of basement dweller never seeing the light as they’re too drunk on the delights of their sex robots, acolytes of cyborg surgery slowly slipping from human to machine. But that’s a long way off – none of those things are nearly advanced enough to truly be addictive yet.

Alcohol, drugs, sex, spending and gambling are far more entrenched in our society than technological addictions. In fact, most of our new concerns are simply sped up versions of the old vices, a faster way to get a fix. And we’re a lot less willing to tackle the more familiar addictions. Cigarettes are far less socially acceptable than they were even in 1998 – which is what makes Billingham’s work feel like a period piece – but despite a dip in drinking among the younger generation, alcohol isn’t going anywhere.

Would it be legal today if it were newly-discovered? It seems very unlikely, but the drug we drink is so ensconced into the culture and economies of western society that violence, addiction and suffering is priced in. It’s far easier for health secretary Matt Hancock to talk tough about setting social media time limits for children, as he did recently, than dealing with drugs, drink or even sugar.

The idea of shutting yourself off from your surroundings didn’t arrive with the internet or the smartphone; that’s one reason that the Walkman was such a global success. Go back much, much further and, in the 18th century, there was a profound moral panic over the novel, this dangerous, cheap and easily accessible product with narcotic effects on concentration and imagination. But it was when the things that demanded our attention became screens that newspapers really got worried about the potential for addiction – first television, then computers, now smartphones – funnily enough all things that stole eyeballs from the traditional press.

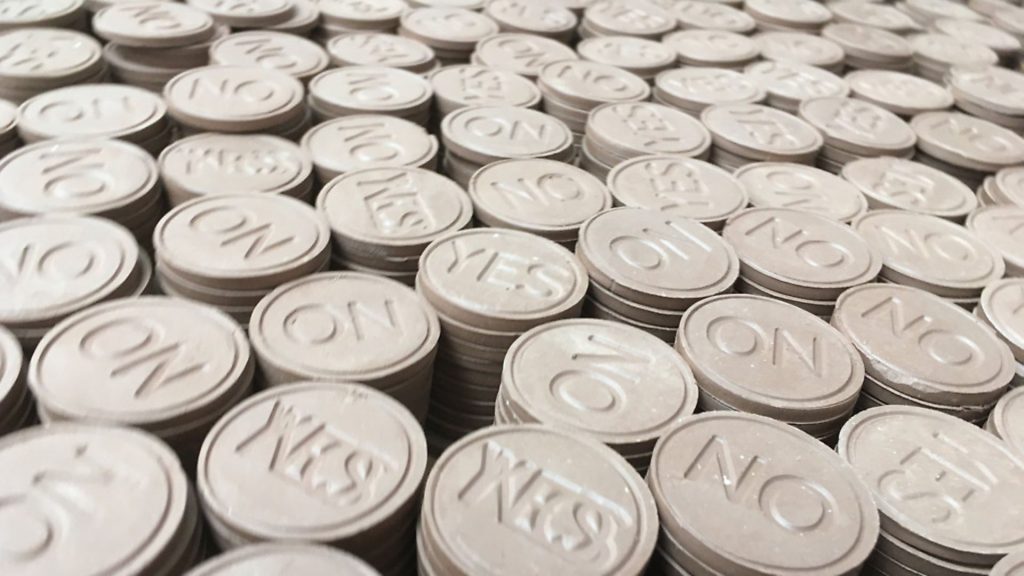

Hooked raises plenty of questions – particularly the work which foregrounds the voices of addicts or, like YoHa’s Database Addiction, Table of Tables, shows the data behind the diseases – but it also left me wanting some more definitive statement on our modern addictions.

There must be an artist out there somewhere who can give us a vision of social media, online gambling and gaming addictions that could match the greasy horror of Hogarth’s Beer Street and Gin Lane prints. They’re probably already on Instagram.

The Hooked exhibition and season of events runs until January 6 at the Science Gallery London. Visit London.sciencegallery.com/hooked

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37