FLORENCE HALLETT on two new books that offer a corrective to the much mythologised early biography of Francis Bacon, and place him at the heart of the European artistic tradition.

At some point in 1944, Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery and chairman of the War Artists’ Advisory Committee, walked into Francis Bacon’s South Kensington studio. The occasion was recorded by Kathleen Sutherland, whose husband Graham Sutherland was Bacon’s friend, and one of the most celebrated British artists of the time: “Interesting, yes. What extraordinary times we live in”, said Clark, before leaving with his “tightly rolled umbrella” on his arm.

It is possible that Clark had just seen Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, paintings that a few months later would announce the unknown painter Francis Bacon (1909-1992) as one of the most notorious and divisive figures of 20th century art.

As Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan put it in Revelations, their new biography of the artist, it soon became clear that “this charming man was intent upon mercilessly attacking every comforting platitude of the 20th century.” If Clark’s reaction seemed curt, more vociferous judgements would follow.

Despite appearances, it turned out that Clark had been impressed by what he saw at Bacon’s studio, telling Sutherland later that evening, “You and I may be in minority of two, but we may still be right in thinking that Francis Bacon has genius.”

It was thanks to Sutherland that in April 1945 Bacon was invited to make up the numbers in an exhibition at the Lefevre Gallery in Mayfair, celebrating two generations of British modernism. Sutherland and Henry Moore, the shining stars of Kenneth Clark’s War Artists’ Scheme, represented the new generation, each having found a distinctive visual language with which to lament the reality of war.

Frances Hodgkins and Matthew Smith were the venerable exponents of a modernist tradition rooted in the Paris of Matisse and the Fauves, and brought with them the gravitas of longevity to an exhibition intended to bring solace to a city exhausted by war.

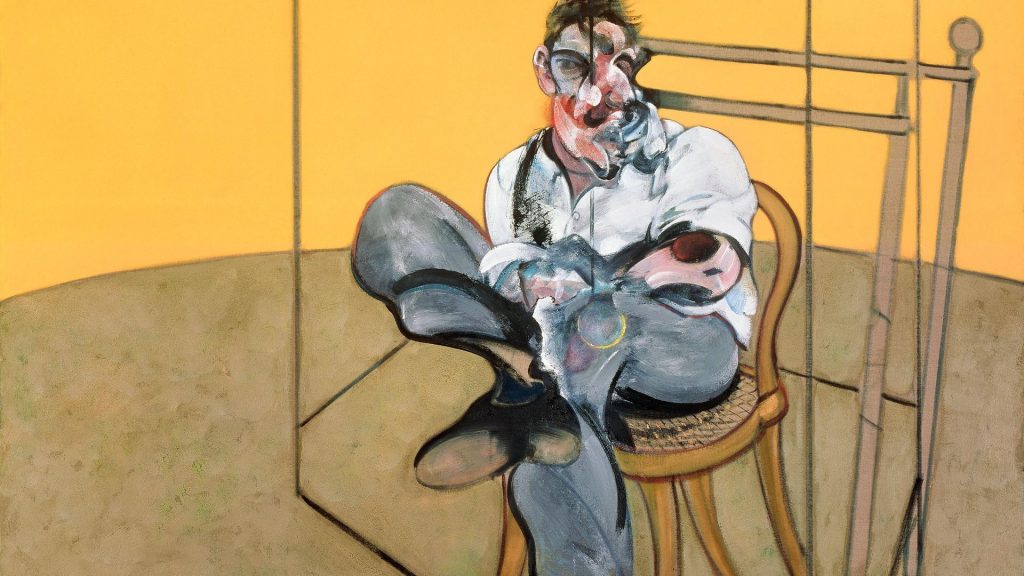

But then there was Bacon. “Immediately to the right of the door were images so unrelievedly awful that the mind shut snap at the sight of them”, recalls the critic John Russell. Set against a sickly orange glow, Bacon’s triptych of tormented, unseeing monsters delivered a physical and psychic assault. Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion caused “total consternation”, said Russell. “We had no name for them, and no name for what we felt about them”.

Crowds gathered, and then retreated, shocked; the catalogue was reprinted three times. The exhibition ran for a month, and Francis Bacon was transformed from a nobody to one of the most talked about artists of his generation.

If Three Studies was a sudden and accomplished debut, this was no accident. As Bacon’s friend Yves Peyré, explains in his recently published book Francis Bacon: The Measure of Excess: “he himself always maintained that his work began with the famous Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion; he rarely demurred from this view and attempted to conceal everything that went before.”

“What went before” is explored in Revelations, and through extraordinarily diligent research, the authors have restored the years between 1927 and 1944, which Bacon had erased with the same efficiency that he would apply to the destruction of his early paintings.

Openly queer at a time when homosexuality was criminalised, and with a taste for violence and rough trade, secrecy would have been a matter of necessity to Bacon. Even before he was aware that he was attracted to boys and not girls, concealment and evasion would have helped him to navigate his bullying father, who disliked his son’s effeminate ways and physical frailty caused by asthma.

Eventually, it allowed an artist who had never received any formal training, and who seemed to have taken years to find his subject and his medium, to emerge with an energy and brilliance that could draw comparisons with Picasso.

Bacon’s life story was shaped in the convivial surroundings of Soho pubs and clubs, where he held forth among friends and admirers, charming and caustic by turns. In the years after the Second World War, Soho was a true bohemia, its cast of odd and raffish characters making regular appearances in Bacon’s paintings. Among them were Isabel Rawsthorne, Lucian Freud, the photographer John Deakin, and the formidable proprietor of the Colony Room, Muriel Belcher.

Bacon’s mythology was shored up with each retelling, and repeated in the biographies written after his death by those who had known him. Aged 17, Bacon had been thrown out by his bullying father who had discovered him trying on his mother’s underwear; in his late teens he had visited Berlin and Paris; he had dabbled in design; in 1944 he begun painting seriously.

To these stories, Revelations is an impressive corrective. Perhaps, suggest Sevens and Swan, Bacon left home because there was very little to keep him there: “He could purchase a train ticket at any time. But there was hardly any drama in that.” Certainly, he was not abandoned: he wanted to join his cousin Diana in London, and his mother provided him with a modest allowance.

Even so, there is no doubt that Bacon’s relationship with his father provided the template for his future taste in physically intimidating men, who took pleasure in giving him a thrashing.

In Bacon’s paintings, brutality and pain are embodied in the muted screams of monkeys and the cowering figures of dogs. They reek of barely suppressed violence, summoned perhaps by the artist’s memory of his horse trainer father and a house full of dogs.

Animals provoked his asthma, a condition that to Bacon’s father was a sign of emotional weakness. He got on better with girls and women than with his own gender, no doubt another failing in his father’s eyes. He may have been raped by a stable hand; certainly he found himself sexually attracted to his father.

For Stevens and Swan, “some volatile sexual compound – father, groom, animal, discipline – gave Francis a physical jolt that helped make him into the painter Francis Bacon.”

From London, Bacon went to Berlin, its nightclubs and cabarets havens of sexual liberation and adventure that allowed him finally the freedom to be himself. For Bacon, the boundaries between sex and violence were already blurred, and his experiences in Berlin, in the company of a depraved and sadistic sexual predator, were formative.

From Berlin, Bacon travelled alone to Paris, remaining there for a year and a half though he would later dismiss it as little more than “a visit”. Yves Peyré writes that “Bacon was deeply in love with Paris”, and his book comes into its own as the perspective of a Frenchman, reminding us that Bacon was rare among his contemporaries for being a truly European artist, who was not only admired abroad, but fully conversant with French culture.

Bacon spoke fluent French, which he learned while living in Chantilly with a French family, the Bocquentins. He had a special bond with Mme Bocquentin, and she cultivated in him an appreciation of art and culture, introducing him to the work of Picasso, and, showing him, write Stevens and Swan, “the sensual joy that could be found in life apart from sex”.

After about nine months, Bacon left Chantilly for Montparnasse, where he channelled his growing interest in Picasso and cubism not into painting, but into designing ultra-modern rugs and furniture. By the time he left Paris in 1928, write Stevens and Swan, Bacon “not only spoke the language but was a committed young designer with good connections and a promising future”.

Back in London, Bacon was fully committed to his promising career as a designer, setting up a showroom at 17 Queensberry Mews in South Kensington, where he lived with Eric Allden, “an upstanding member of the Tory establishment” and Bacon’s first long term relationship.

Fitted out in glass, chrome and elegant, simple lines, the showroom was typical of Parisian modernity, so much so that it made the opening spread in a feature in The Studio magazine, entitled “The 1930 Look in British Decoration”.

Unlike so many artists who have relied on commercial work to earn a living, Bacon had a genuine flair and and fondness for design, and pursued it seriously. Painting was a secondary occupation, and its ideas – particularly cubism – are evident in his design work, such as a painted screen dating from 1930.

By 1932, Bacon and Allden’s relationship had ended, and with it the showroom. From then on, Bacon dedicated himself to the hard graft of painting, experimenting with a multitude of contemporary styles and hustling older, wealthy men to get by.

He exhibited paintings from time to time, but rarely to acclaim, and Stevens and Swan report that his rejection by the International Surrealist Exhibition of 1936 was accompanied by the stinging enquiry: “Mr Bacon, don’t you realise a lot has happened to painting since the Impressionists?”.

Bacon destroyed so much that it is almost impossible to grasp his evolution into a mature artist, and yet the few surviving works of the 1930s, including the spectral Crucifixion of 1933, show that his central ideas were formed early on.

War of course, changed everything. Bacon’s asthma meant that he could not be called up, and yet he seems not to have wanted to avoid active service altogether, joining the Red Cross and the rescue efforts of the Chelsea ARP during the Blitz, but soon finding that his lungs were overcome by dust and debris. He left London for the country in October 1940, to emerge anew in 1944, the year in which, he said, “I began”.

Francis Bacon: Revelations by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, is published by William Collins, £30

Francis Bacon: or the Measure of Excess, by Yves Peyré, is published by ACC Art Books, £45

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion

That the artwork represented a landmark not just in Bacon’s own career but in British art can be surmised from the critic John Russell’s 1971 observation that “there was painting in England before the Three Studies, and painting after them, and no one… can confuse the two”.

Bacon said in a 1959 letter that the figures in the painting were “intended to [be] use[d] at the base of a large Crucifixion which I may still do”, suggesting they were conceived as a predella – or platform – for a larger altarpiece. It has also been suggested that the panels may have emerged as single works, and that the idea of combining them as a triptych came later. The Crucifixion itself is conspicuously absent, and there is no trace or shadow of it in the panels

The mouth of the triptych’s central figure was inspired by the nurse’s scream in Sergei Eisenstein’s Odessa Steps massacre sequence in The Battleship Potemkin.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37