Its author might now be deeply unfashionable, but that shouldn’t put us off The Jungle Book, says CHARLIE CONNELLY.

Who among us doesn’t love a bit of anthropomorphism? For as long as there’s been literature, writers have been putting words into the mouths of the creatures of the earth and in some cases even clothes on their backs and spectacles on their noses. Since Aesop and his fables of the sixth century BC we’ve enjoyed a plethora of babbling beasts, from Peter Rabbit to insurance-punting meerkats in smoking jackets.

Next week marks the 125th anniversary of the book that could be described as the daddy of them all. Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, a set of seven stories set in India and written for his baby daughter, was first published in London at the end of May 1894 and has never been out of print since. It has produced spin-offs, rip-offs and adaptations of which none has come close to the source material for the sheer originality and brilliance of its storytelling.

The Jungle Book also allows us valuable insight into the man who wrote it, one of the most divisive figures in English literature, even 80 years after his death. As recently as January 2017 Boris Johnson narrowly escaped a diplomatic incident when, as foreign secretary, he gave a sotto voce recitation of Kipling’s Mandalay while a guest at a ceremony at the Shwedagon Pagoda, Myanmar’s holiest Buddhist site. Johnson was abruptly shushed by the British ambassador, who pointed out the poem, was “not appropriate”.

Only last summer students at Manchester University painted over a mural displaying Kipling’s best-known poem If, on the grounds that he “dehumanised people of colour”, and there is no more stark demonstration of his controversial standing today that a man roundly condemned as representing the absolute worst of British imperialism should have composed the poem regularly affirmed as the nation’s favourite.

The Jungle Book was written far from India and far even from the England that lay at the heart of Kipling’s vehement imperialism. He was already a world- famous writer of short stories and poems when, in 1891, he set up home in Vermont with his new wife Caroline.

Born in India in 1865, Kipling’s idyllic early childhood of colonial privilege had been abruptly truncated when he was sent back to England at the age of six. A decade later, having failed to win a scholarship to Oxford and with his Lahore-based art professor father unable to afford the fees without one, the 16-year-old Kipling returned to India to take up a job on a newspaper.

He flourished as a journalist and then as a writer, first with his collection of short stories Plain Tales From The Hills published in January 1888, followed by an astonishing six further books of short stories the same year. In 1889, at the age of 24, he set off for the bright literary lights of London via a route that took in a mazy wander across America, where he met Mark Twain and the woman who would become his wife. But his stay in England was brief, ended by a mental breakdown leading to a long journey prescribed by his doctor. Kipling re-crossed the Atlantic, married his American sweetheart and settled in Brattleboro, Vermont, where their first child Josephine was born in the wintry final days of 1892.

As he looked out across the snowy landscape Kipling found his thoughts drifting back to India, prompting a new set of stories, some of which concerned a young boy raised by wolves and enjoying the protection of other animals in a rigid jungle hierarchy. The seven stories, the first three of which told the story of Mowgli, were written for his baby daughter.

The Jungle Book was an instant success. “The whole book is fresh, vigorous and brilliant and thoroughly worthy of the reputation of its author,” said the St James Gazette, while for the Scotsman “the book will compare favourably with any anthropomorphic tales ever written”.

It is almost impossible now to grasp just how popular Kipling’s writing was when The Jungle Book was published. Many were convinced he was the man to assume the role of Britain’s greatest writer left vacant since the death of Charles Dickens in 1870, and in 1907 he would become the first English language writer to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature.

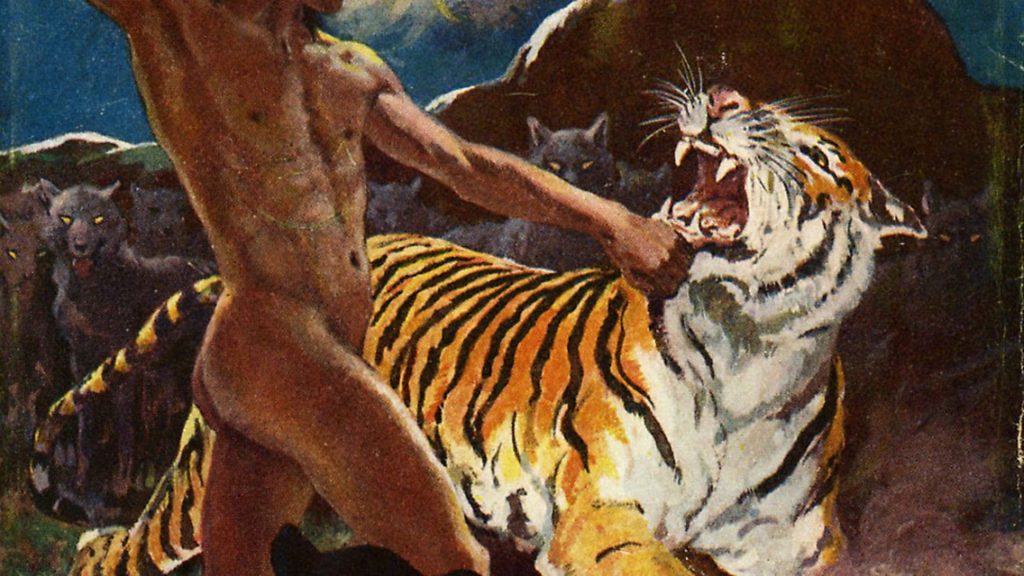

It’s also hard to imagine just how original and exciting The Jungle Book must have been to its earliest audience. For most of us today it conjures up images from the 1967 animated version with its dancing bear and snake with psychedelic eyes, but Walt Disney’s was an interpretation that played fast and loose with the original source material: when Disney handed screenwriter Larry Clemmons a copy of the book he said, “the first thing I want you to do is not read it”. The goofy, wisecracking Baloo, for example, is a long way from the wise, guiding and occasionally brutal bear of the original stories, in which Baloo, along with Bagheera, beats Mowgli during lessons in jungle survival.

The Jungle Book also established India as a literary destination where previously it had been largely the preserve of travelogues by walrus-moustached men with letters after their name intent on shooting dead any animal they encountered. In Kipling’s India, Mowgli had been raised in the jungle by wolves after being separated from his parents during an attack by the tiger Shere Khan.

His upbringing away from the traditional family unit is part of a wider theme of childhood abandonment in Kipling’s work that also underpins Kim and Captains Courageous, where young boys also find themselves alone and living on their wits in hostile environments.

You don’t have to look far to find a clear resonance with Kipling’s own life. When he was sent back to England as a boy he lodged with a retired naval captain and his wife in Southsea, Hampshire, who boarded children of emigrant parents. While the captain showed the young Kipling notable kindness his death left the boy solely in the care of the brutal Sarah Holloway. An evangelical Christian, Holloway unleashed on her charge the full fire and brimstone, beating him regularly and on one occasion sending him to school with a sign around his neck reading, “Kipling the Liar”.

“I have known a certain amount of bullying but this was calculated torture,” wrote Kipling in his posthumously-published 1937 memoir Something Of Myself. “Yet it made me give attention to the lies I found myself having to tell and this, I presume, is the foundation of my literary effort.”

When his aunt, whom he visited every Christmas, became worried about the boy’s health and his poor eyesight in particular she sent a doctor to check on him, an act for which Kipling was later punished for “showing off”. His mother, alerted to her son’s predicament by her sister, returned from India and when she walked into his room observed how, by instinct, the boy threw up his arms to protect himself.

The fallout from Kipling’s horrific English childhood can possibly be detected in the man he became, a chronic insomniac prone to angry outbursts and bitter hatreds who was over-protective of his own children. The tragedy of losing his son John, killed at the Battle of Loos in 1915, after Kipling had pulled strings to allow him to enlist despite dreadful eyesight, is well known but it is a story that overshadows the fate of Kipling’s eldest child, Josephine, for whom The Jungle Book was written.

In 2010, a first edition of the book was discovered in a house in which Kipling’s youngest daughter Elsie had once lived. On the flyleaf the author had written, “This book belongs to Josephine Kipling for whom it was written by her father, May 1894”. Five years after Kipling inscribed the book six-year-old Josephine was dead, falling victim to pneumonia in March 1899. Her father, also stricken by the illness, was not told for several days, until his health had improved. The loss of the daughter on whom he doted affected him dreadfully, at least as much as the death in battle of John Kipling.

Also running through The Jungle Book is the necessity for a strict observance of the law in a civilised society, something that obsessed Kipling throughout his life. The jungle in which Mowgli grows up is no hotbed of Darwinian competition. There is an advanced set of laws by which all the animals abide, except the Bandar-log monkeys, who are regarded as uncivilised outsiders. This constant desire for adherence to authority is possibly what lay behind Kipling’s devotion to the British empire; as far as he was concerned it was a necessary and improving method of imposing order at whatever cost.

It would be quite wrong to defend Kipling’s less palatable views as those of a man of his time. From the turn of the 20th century in particular he was widely criticised as he expressed an increasingly scattergun range of hatreds. Kipling had been an ardent imperialist from the start, even at 18 strongly condemning a bill that would allow Indians to try Europeans in their courts. In the story His Chance In Life from his first book Plain Tales From The Hills he wrote: “Never forget that unless the outward and visible signs of Our Authority are always before a native he is as incapable as a child of understanding what authority means, or where is the danger of disobeying it.”

The words are those of a fictional narrator but it’s safe to say they reflected those of the author: he once wrote to a cousin that “in spite of what good lies in the native he is utterly unable to do anything finished, clean or neat unless he has the Englishman at his elbow to guide and direct and put straight”.

In the years leading up to the First World War Kipling found himself increasingly on the wrong side of history, railing against the suffragette movement and becoming a committed Unionist. He referred to the Irish Free State as “the Free State of Evil” and the Irish themselves he dismissed as “the Orientals of the West”, shoehorning in a dig at another of his bugbears, the Chinese. As well as the Irish, the Chinese and the suffragettes he hated the Germans, the Slavs, Bolsheviks, the Labour Party (“Bolshevism without bullets”) and fascists, yet he was well-disposed towards Muslims and the Japanese, had what certainly for the time was an open-minded attitude to sex and relationships and was a devoted Francophile.

Kipling was always a man out of place, a foreigner and an outsider wherever he went. In India and America he was an Englishman, in England he was Anglo-Indian and would never truly be part of any community beyond the hardened image of empire he inhabited in his head, the kind of doomed, narrow, self-defeating notion of British supremacy whose death throes we’re witnessing as part of the Brexit debacle.

Meanwhile The Jungle Book remains as fresh and exhilarating as ever and even contains much with which we can legitimately identify today. Although Kipling would have been among the most ardent Brexiteers, there’s certainly something familiar in how the Bandar-log “boast and chatter and pretend that they are a great people about to do great affairs in the jungle” and how they sit “dreaming of deeds we meant to do, all complete in a minute or two. Something noble and wise and good, done by merely wishing we could”.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37