The small South American nation has produced two exceptional bandleaders from two different eras, who helped transform music in the UK

Georgetown is 3,500 miles across the Atlantic from Britain, but it has exercised a huge influence on the music of the imperial mother country.

This little city of low-rise colonial architecture, with the unspoilt jungle lying beyond, was still firmly under the rule of Britain, its rum and molasses the country’s major exports as they had been two centuries before, when Kenrick Johnson was born there in 1914. As Ken ‘Snakehips’ Johnson he would become one of the most flamboyant bandleaders of wartime London and begin a tradition of Guyanese musicians shaping British music.

It was in vain that Johnson’s father sent his 15-year-old son – a violinist and natural dancer – to a Buckinghamshire grammar school with a career in medicine in mind. The young Kenrick instead took up dance, touring the Caribbean and catching the tail end of the Harlem Renaissance in New York. There he encountered Cab Calloway, on whom he would largely model himself. His sinuous dancing gained him his stage moniker, but the heady mix of musical influences he soaked up during his travels – from Trinidadian calypso to hot Harlem jazz – also led Johnson to form a swing band back in Britain.

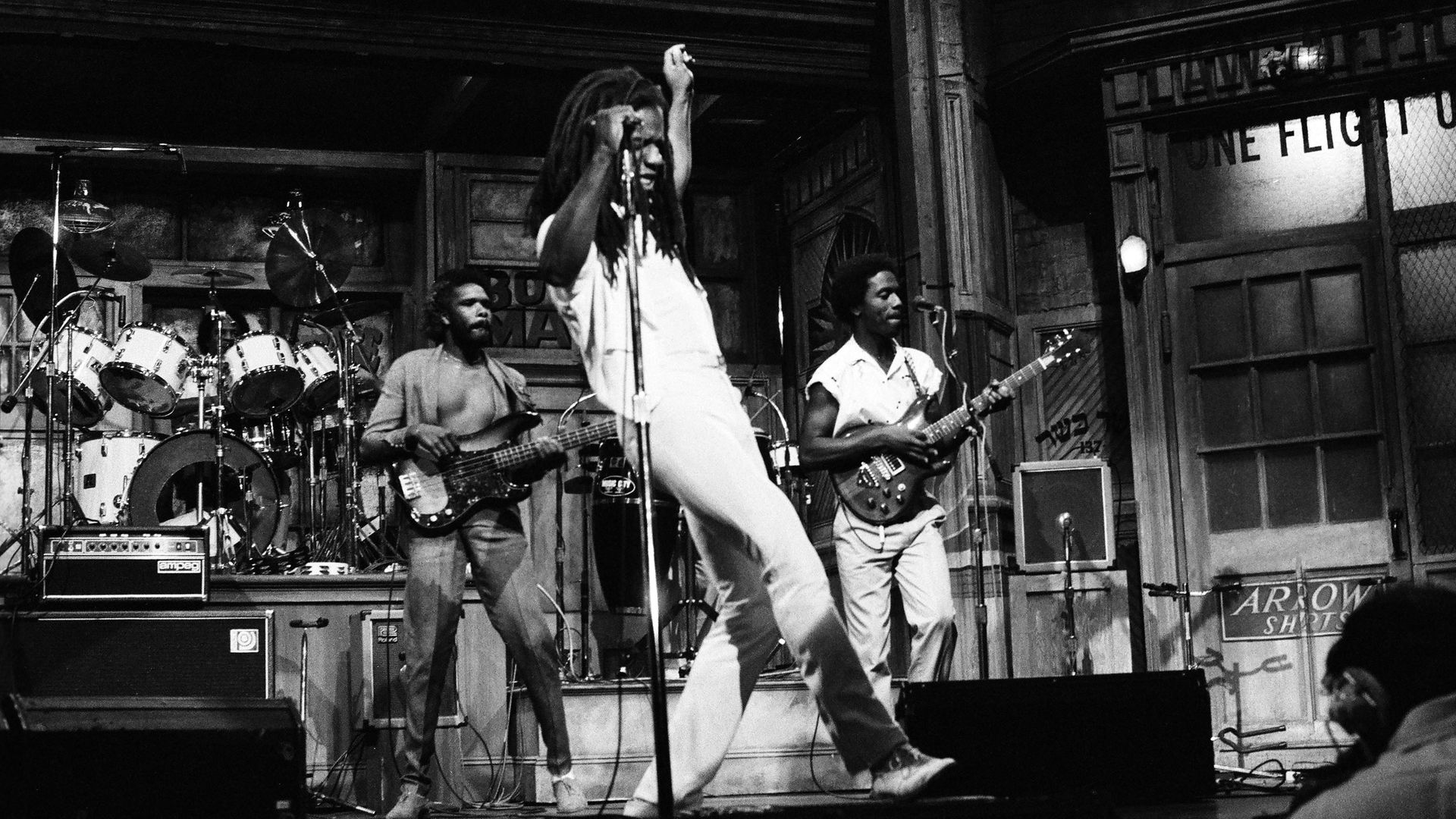

Founded in 1936 with Jamaican trumpeter Leslie Thompson, the Rhythm Swingers had both West Indian and white players. Later becoming the all-black West Indian Dance Orchestra, and with born showman Johnson as its dynamic leader – at well over 6ft tall and clad in white tails, he was an undeniably striking figure – the act gave the local swing bands a serious run for their money in pre-war London.

Melody Maker called the West Indian Dance Orchestra “dance-inducing”, and indeed the fundamental difference between the Orchestra and the British bands was that they swung harder, at a less moderate tempo and with a sound that came directly from African American swing. The BBC had begun broadcasting the Orchestra on the eve of the war and by 1940 they had a regular slot performing at the Café de Paris, the very embodiment of elegant wartime London nightlife.

It was the night of March 8, 1941, and the height of the Blitz as Johnson’s orchestra played their signature tune Oh Johnny from the stage of the Café de Paris. Seconds after Johnson took the stage to join them, the club took a direct hit from two bombs.

Johnson, then just 26, was killed instantly. Melody Maker’s obituary called him “one of the most progressive disciples of modern swing in this country”, and noted he was “one of the nicest men it was possible to meet. Intelligent, highly educated and courteous”, and Johnson left behind a legacy for Guyanese artists of making it on the British stage, throwing down the gauntlet to several generations to come.

Both Britain and Guyana had entered a new age by the time the next wave of Guyanese artists to make it abroad emerged. Windrush and mass immigration had made the West Indians that had been a curio when they appeared under Ken Johnson’s baton a part of everyday British life, and Guyana got a new constitution in 1953 which brought home rule and the first elections.

But the new far left government soon spooked the British, who immediately suspended the constitution and sent in the troops, and inter-ethnic violence between the descendants of African slaves and those of the indentured Indian labourers brought to Guyana after the abolition of slavery followed, before the British cut the troubled colony loose in 1966.

It was amid such change that both calypso star and later Guyanese MP and government minister Lord Canary (Malcolm Corrica) and Caribbean soul singer Johnny Braff (Johnny Critchlow), both born in Georgetown in 1937, began making a splash.

Like R. B. Greaves – nephew of Sam Cooke, frontman as ‘Sonny Childe’ of British mod band The TNTS and singer of the soul hit Take a Letter, Maria (1969), who was born on the US Air Base at Georgetown in 1943 – both Canary and Braff performed in the US and saw their recordings echo down the years in Britain, feeding into the pool of influences that informed Northern Soul, the mod revival and 2 Tone. But in more mainstream sounds, a band emerged in the year of Guyanese independence that would repeat Ken Johnson’s founding of a multi-racial British band 30 years before.

Having met on a Hornsey Rise council estate, The Equals comprised the Jamaican-born Gordon brothers, white native Londoners Pat Lloyd and John Hall, and trumpeter-turned-guitarist Eddy Grant, born in the village of Plaisance, a few miles outside central Georgetown, in 1948. Formed the year of the 1965 Race Relations Act, their name was apt, and they were a prominent interracial band at a time when, whatever the new law said, there was still considerable racial tension.

The 1958 Notting Hill riots and the 1962 act that had limited immigration from the Commonwealth were not such a distant memory as The Equals released their debut single, the driving mod pop of I Won’t Be There (1966).

While the single did little business, the later Baby Come Back – a chugging, unmistakably Jamaican-accented instant pop classic – ended up at UK No. 1 for three consecutive weeks in the summer of 1968. Originally appearing as the B-side to Hold Me Closer in 1966, it had already gained radio play and Top 10 sales across Europe.

The song even broke the US Top 40, and the band – just out of their teens and wearing the bright peacock fashions of Carnaby Street – were as visually striking as their hybrid sound was beguiling.

While The Equals only had two further UK Top 10 hits, their legacy was a considerable one. Grant’s anti-war, utopian funk track Black Skinned Blue Eyed Boys (1970) (“People won’t be black or white/ The world will be half-breed”) and the self-explanatory Police On My Back (1968) presaged him becoming an important black British voice after establishing a solo career. A heart attack at 23 had seen him leave The Equals and return to Guyana for a time to recover, before he moved to Barbados and opened a successful studio there.

Production work for other artists, including his brother Rudy under the name The Mexicano followed before Grant’s debut solo single Living On the Frontline (1979), a brooding electronic reggae track which denounced violence in Africa and the Middle East, appeared.

Four years later Electric Avenue (1983), a response to the 1981 Brixton riots, was a huge hit. Both Grant’s political relevance, and the way he injected something of Guyana into the bloodstream of British music, was clear in The Specials later covering Black Skinned Blue Eyed Boys, and The Clash recording Police On My Back for Sandinista! (1980). Such is Grant’s importance back home that in 2005 he appeared on a series of Guyanese postage stamps.

While acts like Terry Gajraj, purveyor of the African/East Indian fusion sound of chutney in the 1990s, and Salsoul Records’ Rafael Cameron, made their names after moves to the US, the colonial past meant Britain benefitted from the best of Guyanese talent, changing its music forever.

PROFESSOR OF DUB

Born Neal Fraser in Georgetown in 1955, Mad Professor moved to London aged 13, bringing the influence of the reggae, calypso and American soul he had heard on the radio back home with him. Gaining his nickname for his love of tinkering with electronics, Mad Professor’s Dub Me Crazy series, beginning in 1982, took dub into a new, electronic age. He had already established Ariwa Records in his Thornton Heath front room by that time. The label would become a British reggae legend and collaborations with Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and remixes for Massive Attack and others have seen his relevance endure.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37