CHARLIE CONNELLY reports on the quest for the remains of a writer likened to the Bard, and the posthumous activities of other great authors.

Imagine if William Shakespeare’s remains were no longer in his grave inside Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon. Imagine if they’d been lost, possibly in an act of desecration during a traumatic 20th century civil war, and nobody can say for certain what happened to the bones of the greatest playwright in the history of these islands.

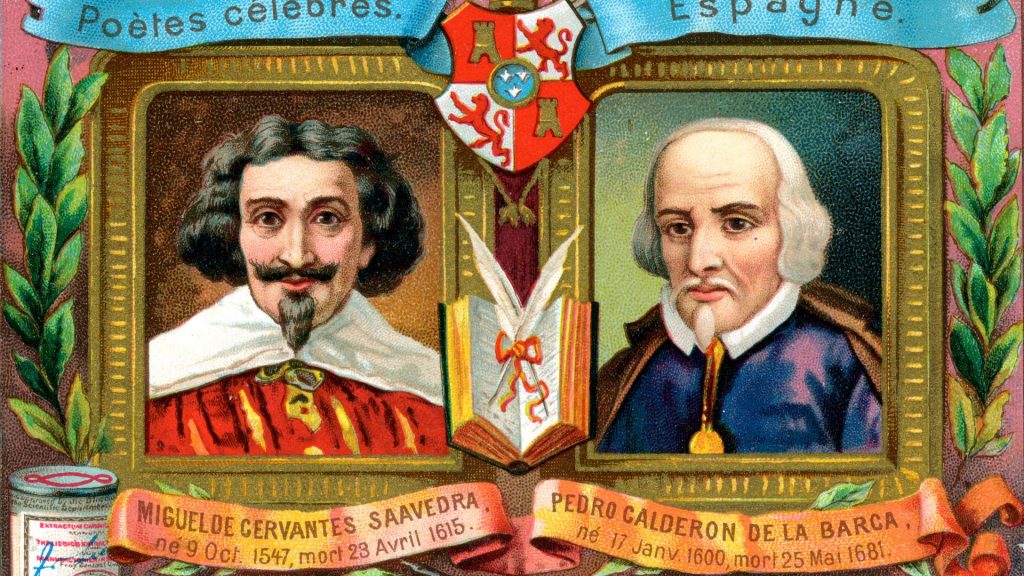

That’s been the situation in Spain since 1936 when Republican forces torched the church of Nuestra Señora de los Dolores in Madrid, destroying a marble casket containing the remains of Pedro Calderón de la Barca in the process. It’s 340 years this year since the playwright’s death at the age of 81, an anniversary set to be marked by the retrieval and reburial of his missing remains.

Calderón de la Barca was a shining literary light of Spain’s 17th century Golden Age and is still regarded as arguably the finest dramatist in the history of the nation. Unusually for the time, his plays were translated and performed abroad, with Samuel Pepys attending a performance of La vida es sueño (‘Life is a Dream’) in London in 1667, enough of a fan to own two of Calderón de la Barca’s works as part of his carefully compiled library

Calderón de la Barca began writing plays in his early 20s and over the course of the next two decades produced more than 70, more than twice the number Shakespeare wrote in his lifetime. A prolific output even if writing was a full-time occupation, but for half that period he was a soldier in the Spanish army, fighting in campaigns across Europe from Flanders to Italy.

In 1651 he took holy orders and moved away from secular works to write autos sacramentales, roughly equivalent to the morality plays popular in England under the Tudors, and by 1663 he had risen to become honorary chaplain to Philip IV. He was still writing plays on the threshold of his ninth decade, his last produced in honour of Charles II’s marriage in 1679.

Calderón de la Barca remained popular long after his death even outside Spain: among those who translated and staged his works were Goethe and Shelley, while as recently as the 1950s Boris Pasternak was rendering Calderón de la Barca’s works into Russian.

When he died in 1681 he was buried as he wished, “uncovered, as if I deserved to satisfy in part the public vanities of my poorly spent life”, but endured a peripatetic afterlife. When his bones arrived at Nuestra Señora de los Dolores in 1902 it was the seventh time they’d been moved.

This reburial was quite different to what he might have had in mind when he condemned his “poorly spent life” (before taking holy orders he was renowned as a pugnacious heavy drinker always in dire financial straits). The writers and intellectuals of the day insisted that a man of such cultural importance should be granted a ceremony commensurate with his status and a grand procession was arranged through the centre of Madrid. Thousands lined the streets as the playwright’s remains were transported in a carriage pulled by six white horses, the parade pausing in front of Spain’s national theatre while rose petals were scattered on the steps. It might have been the antithesis of his dying wishes but the ceremony affirmed Calderón de la Barca’s standing as one of Spain’s greatest cultural figures.

Then on July 21, 1936, in the early stages of the Spanish Civil War, militiamen rampaging through the streets of Madrid set fire to Nuestra Señora de los Dolores. The building burned for two days, the roof collapsed and the interior was completely destroyed. Nine people died.

After the war the slow process of rebuilding and restoring commenced while a chaplain named Vicente Mayor began to research the history of the parish, a difficult task considering how much of the archives were destroyed in the blaze. In a book published in 1964 Mayor recounted an interview he conducted with an elderly priest in poor health who, when Mayor expressed sorrow at the loss in the fire of the remains of Calderón de la Barca, told him, “Don’t worry, the remains have not disappeared because they were not in the marble casket. They were placed in a hole in the wall at the start of the war for safe keeping”.

The priest promised that as soon as he was well enough he would show Mayor the spot where Calderón de la Barca’s bones had been hidden, but he died soon afterwards. Mayor took on the task of finding the bones himself and despite drilling a number of holes in the walls he could find no trace, even turning to a renowned exorcist named Father Pilón for help who also failed to find anything.

“Who knows if one day the discovery will be made?” wrote Mayor at the end of his book. “It’s not out of the question by any means.”

Two years ago a group of academics, archaeologists and ground-penetrating radar experts began Operation Calderón designed to research in depth the circumstances of the writer’s posthumous travels, locate the remains and, if successful, publish their findings and reinter the playwright, hopefully by the end of this summer.

The scanning began last month overseen by Luis Avial, a ground-penetrating radar specialist responsible for finding the remains of more than a hundred missing victims of the Spanish Civil War.

“We don’t know where the bones are hidden but we’ll start with the chapel, which would seem to be the logical location, and take it from there,” he said.

Six years ago Avial was involved in another search for a long-lost literary giant when he helped to identify the casket containing Don Quixote author Miguel de Cervantes in a Madrid convent.

Cervantes had been buried there following his death in 1616 but when the convent was rebuilt at the end of the 17th century the exact location was lost but Avial helped find the casket among the remains of 300 other people in a forgotten crypt. The search for Calderón de la Barca should be simpler, he said, because this time “there should only be him in the walls”.

It’s not only Spanish writers who endure such posthumous adventures. Dante Alighieri suffered a similar fate to Calderón de la Barca when he died in 1321. He was buried in Ravenna then, when church officials grew concerned that a party from the author’s home city of Florence would reclaim the body, was exhumed and his remains hidden inside a church wall. There they stayed, forgotten, until they were unearthed by a stonemason undertaking renovation work during the mid 19th century. The discovery brought crowds flocking to the church, where lax security meant several bones were spirited away and could now be scattered all over the world.

When Voltaire died in Paris in 1778 he was concerned, with good reason, that his criticisms of the church would deny him a Christian burial and see his remains disposed of with neither ceremony nor dignity so the writer’s nephew hatched a plan. Before word of his uncle’s demise could spread he carried the corpse to a carriage and secured it in a sitting position, posing Voltaire as if he was still alive with the intention of transporting the body for burial on his estate at Ferney. It was a five day journey, but by the end of the first it was clear the corpse wasn’t up to the jolting odyssey along rutted roads so he was interred at a monastery en route instead. In 1791, after the French Revolution, he was exhumed and reinterred at the Pantheon in Paris.

Also in Paris lies René Descartes who died in Stockholm in 1650 but has a grave in a Parisian church that many claim is actually occupied by somebody else altogether. His head is definitely not there, having been stolen by a Swedish soldier supposed to be guarding it. The skull was written and drawn on before coming into the possession of a tax inspector named Ahlgren who wrote his name behind where Descartes’ left ear would have been. The philosopher’s skull now resides at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris.

Another great writer who died away from his home country was W.B. Yeats, buried at Roquebrune-sur-Cap on the French Riviera in 1939 having asked to be interred at Drumcliffe in County Sligo. The war intervened, however, and when enquiries were made in the late 1940s it turned out Yeats and others had been exhumed and their bones placed all together in an ossuary. Some say the occupant of Yeats’ Sligo grave is more likely to be an Englishman called Alfred Hollis who was originally buried next to the poet, or it’s just occupied by a random mixture of bones.

Other great writers to suffer posthumous trauma rather than eternal rest include John Milton, whose body was exhumed in the late 18th century during renovations at St Giles, Cripplegate, in London, where workmen took away hair and teeth and sold glimpses of the skeleton for the price of a pot of beer. In 2006 Boris Pasternak’s grave at the Russian writers’ retreat Peredelkino was damaged when wreaths from around the cemetery were piled on top of the tomb and set alight in a conflagration so fierce it damaged neighbouring graves too.

Six years later Peter Pan creator J.M. Barrie’s final resting place in the cemetery at Kirriemuir was vandalised when the coping stones around its edge were picked up and thrown onto the grave, while Sylvia Plath’s headstone, commissioned by husband Ted Hughes, has long been targeted by fans who blame Hughes for her suicide in 1963. The ‘Hughes’ in Sylvia Plath Hughes has been obliterated on at least three occasions.

Perhaps the most alarming story concerns Tristram Shandy author Laurence Sterne, who was a victim of bodysnatchers shortly after his 1768 burial in London. His corpse was dug up and sold for dissection to an anatomy professor at Cambridge University who opened the coffin and immediately recognised Sterne. The writer had been a student at Cambridge and at the time of his death was one of the biggest celebrities in the land. The body was quietly returned to the cemetery; it’s not known if the professor, who some accounts say fainted on the spot, received a refund.

Bodysnatching was a serious problem even in Shakespeare’s day, and the Bard was clearly concerned about what might become of his mortal remains. The slab over his grave displays an inscription apparently written by Shakespeare himself on a stone that doesn’t even bear his name, just the lines “Good friend for Jesus sake forbeare, to dig the dust enclosed here. Blessed be the man that spares these stones, and cursed be he that moves my bones”.

The curse might not have worked: in 2016, 400 years after the death of the Bard, a scan was undertaken of his final resting place that revealed significant disturbance where his head should be, suggesting his skull is most likely missing. Rumours that a local doctor stole the skull during the 1790s have persisted locally since the memoirs of a Warwickshire man first told the story in the late 19th century.

If the efforts of the Madrid researchers bear fruit, however, at least there’s a good chance that Shakespeare’s Spanish equivalent might be found with all bones accounted for. By summer, if all goes to plan, he should also be laid to rest in a permanent grave, suffering no more of the posthumous indignities he’s shared with many of his literary colleagues.

FIVE GREAT BOOKS OUT THIS MONTH

EMPIRELAND: HOW IMPERIALISM SHAPED MODERN BRITAIN

Sathnam Sanghera (Viking, £18.99)

Britain’s apparent inability to look within itself and confront all aspects of its imperial legacy has contributed much to the nation’s reduction in global influence and the simmering anger that produced chronic own goals like the Brexit vote. Journalist and bestselling author Sathnam Sanghera goes deep into the fabric of our society to examine how the tentacles of imperialism reach into every aspect of life in the United Kingdom today.

QUEER: A COLLECTION OF LGBTQ WRITING FROM ANCIENT TIMES TO YESTERDAY

Edited by Frank Wynne (Head of Zeus, £25)

From Sappho and Catullus to Armistead Maupin via Emily Dickinson and Alison Bechdel, this is an absorbing anthology of the queer experience as expressed through centuries of great writing. An outstanding celebration of voices that were for too long oppressed and silenced.

CHILDHOOD, YOUTH, DEPENDENCY

Tove Ditlevsen (Penguin Modern Classics, £9.99)

Tove Ditlevsen is regarded as one of Denmark’s greatest writers but has rarely been published in English. This volume collects the three volumes of memoir she wrote at the end of the 1960s known as the Copenhagen Trilogy. Growing up in a working class area of the Danish capital, she endured a troubled childhood then a descent into addiction thanks to a sinister, gaslighting husband.

ASYLUM ROAD

Olivia Sudjic (Bloomsbury, £14.99)

When Anya agrees to marry Luke after a road trip from London to Provence and back she finds herself forced to confront a past in which she fled a besieged Sarajevo as a child, an experience that left her struggling to cope with the notion of safety and security. A beautiful novel of borders physical, historical and psychological.

A SWIM IN A POND IN THE RAIN

George Saunders (Bloomsbury, £16.99)

One of the most original fictional voices writing today, Booker Prize winner Saunders here lets readers in on the master’s degree course he teaches at Syracuse University on the Russian short story. These seven essays provide invaluable insight into the mechanics of storytelling as well as showing how narratives can enrich an enhance our lives.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37