TIM BALE assesses whether the deal with the EU means politicians on both sides of the debate will finally emerge from the trenches

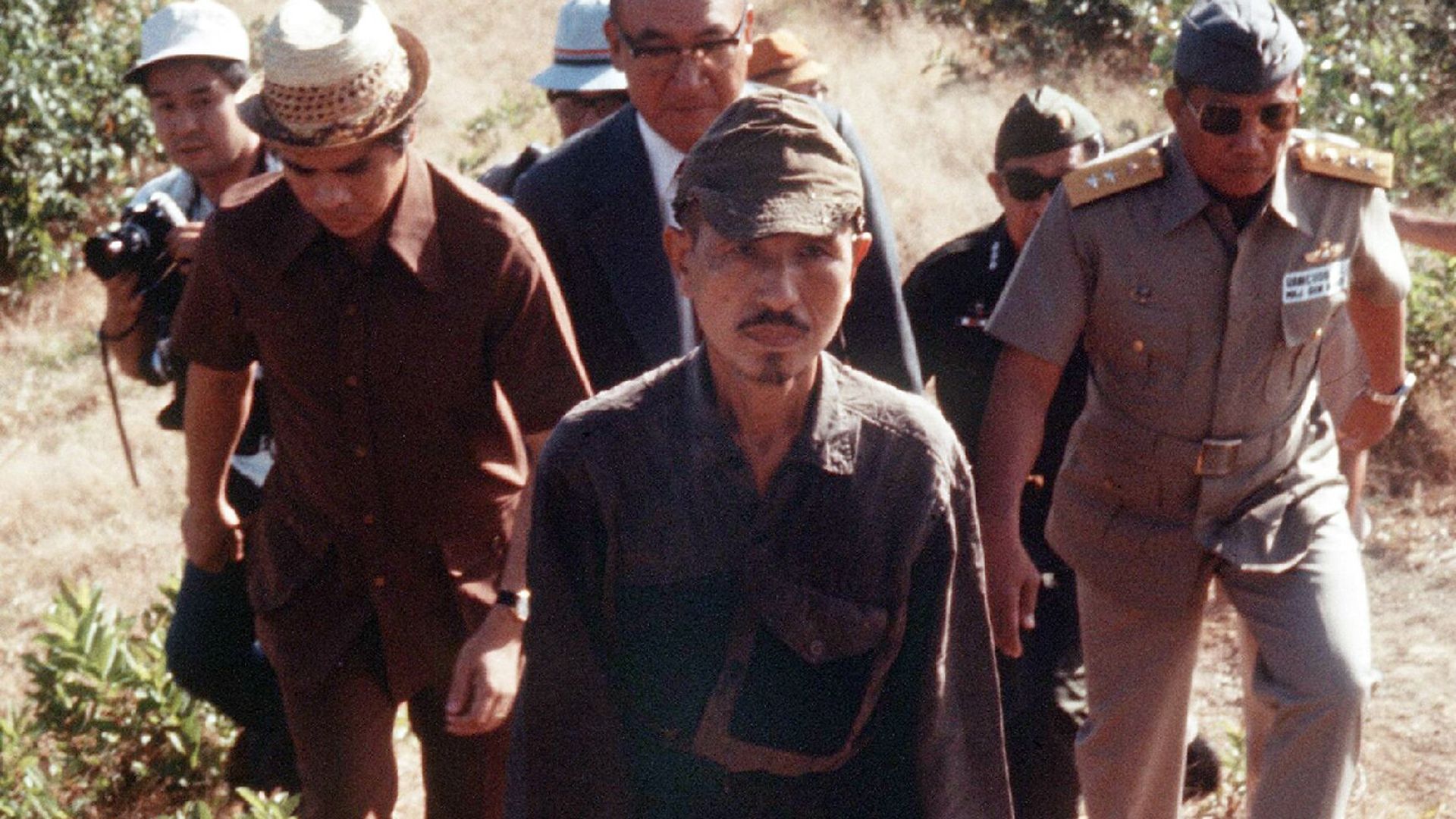

Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda of the Imperial Japanese army took some persuading before he would agree to hand over his sword, his rifle, and the dagger with which he intended to commit suicide should he ever be captured by the Americans. It was March 1974.

In the wake of the UK/EU deal, it is all too easy to assume – especially now Nigel Farage (commander in chief of the People’s Army, no less) has declared the war over – that all those who fought for Brexit will likewise declare victory and return to whatever they were doing (presuming they can even remember what it was) before hostilities commenced.

But that is to forget quite how convinced, obsessed even, that those who laboured so long in the wilderness had to be in order to carry on a fight that for decades looked completely hopeless to their bemused friends, family and colleagues.

For the vast majority of Conservative MPs (most of whom, remember, have either always been or have become Brexiteers), sheer bloody relief, along with a natural inclination to toe the party line and support their leader, will prove a powerful painkiller.

It will inure them to those parts of the deal that have involved more compromise than ideally they would have liked – so much so, perhaps, that they will deny, even to themselves, that any such compromises have even taken place at all.

Fishing communities may cry foul and trade experts may make clear the extent of ongoing alignment, potential sanctions, and ongoing negotiations inherent in the 1,246 pages of dense legal text.

But all that, most Tory Brexiteers – even those who share former Brexit secretary, David Davis’s concerns about the lack of proper scrutiny the rush to ratify involves – will argue, is to ‘fail to see the bigger picture’.

True, Peter Bone – every inch a Brexiteer ultra – is right to issue a warning that, like budgets, the agreement might look good at first glance but could end up rapidly unravelling; but he forgets that it is vanishingly rare, even when that does happen, for his colleagues to vote against the ensuing Finance Bill.

It’s also important to note that the party in the media – the collection of leader writers and the columnists who write for Tory-supporting newspapers – seems to have made up its mind that Johnson has pulled off a miracle.

Moreover, ConHome’s snap survey suggests getting on for two-thirds of grassroots Tories approve – not to be sniffed at when fear of one’s constituency association has often decided which way Conservative MPs have jumped on the European issue.

For Bone and the Bill Cashs of this world – those Tory MPs who like to talk about setting up a ‘Star Chamber’ to examine the small print of the agreement – that small print really matters.

If they decide that it really won’t do, then they (possibly to the tune of ten to twenty colleagues) might well decline to support it in the Commons this week. (The vote comes after this newspaper has gone to print). And they will, like Lieutenant Onoda, then continue the battle by other means for years to come.

Quite what those other means will be – whether, for example, the future relationship between the EU and the UK will on occasion necessitate primary legislation that can be sabotaged by a determined band of parliamentary guerrilla fighters – remains to be seen.

Experience, however, surely teaches us that those whose Euroscepticism has over the years sometimes shaded into Europhobia, even paranoia, are unlikely to give up easily.

As things stand right now, it is difficult to see them having more influence on the course of history than Onoda and his fellow holdouts did after 1945; but many would have said the same about anti-EU Conservatives in 1975.

Meanwhile, what about the other side – those opposition MPs whose determination to keep the UK in the EU saw them campaign for Remain in the referendum and then do all they possibly could to prevent Theresa May and Boris Johnson carrying out what they insisted was ‘the will of the people’? Will they simply ‘go gentle into that good night’? Or will they instead ‘rage, rage against the dying of the light’?

Labour MPs, it seems, are deciding not so much between going gently and raging but just how gentle the going should be: should they vote for ratification as their leader is asking them to so as to hasten Labour’s reconciliation with the Leave voters who deserted the party after 2016 or, knowing there is no danger of the government losing, abstain and risk being accused of arguably counterproductive virtue signalling?

In the end, though, one suspects most will just want the whole thing over with so the party can move on to attacking the government on what the public sees as its poor record on handling the Covid-19 crisis.

For the UK’s third and fourth parties, the SNP and the Lib Dems, however, such signalling makes perfect sense.

For the Nationalists, the end of transition marks the end of the process by which, as they see it, London has ripped Scotland out of the EU against its will – something they will be reminding voters of come spring’s Holyrood elections, which will be the platform from which (all being well) Nicola Sturgeon will launch in earnest her party’s campaign for a second independence referendum.

As for the Lib Dems, refusing to support ratification provides an invaluable opportunity not only to differentiate themselves from Labour but to send a message to Remain voters in the numerous Tory-Lib Dem marginals they need to target if they are to win seats at the next general election.

A spot of raging (metaphorically speaking, of course) should also provide them with at least a little airtime and a few column inches when both have been desperately hard to come by in recent months – something they could badly do with in crucial local elections taking place in a few months’ time.

All this, of course, assumes that Boris Johnson’s achievement will have an electoral half-life longer than most political events ever do – even those that seem especially momentous at the time.

In reality, however, voters have both very long and very short memories. Last week’s agreement – and the parties’ reactions to it – could imprint itself indelibly. But don’t bank on it. Given the pandemic and its economic consequences, a fairly thin free trade agreement with the EU may be the last thing on people’s minds in four years’ time.

Professor Tim Bale is deputy director of UK in a Changing Europe, which first published this article

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37