To be designated as a “record man” is akin to being a secular saint in the music industry. For a “record man” is an archetype of sorts: the guy who founds record labels and develops new sounds and discovers musicians who go on to achieve legendary status while often proving as brilliant in the recording studio as he is in cutting deals.

Yet the term “record woman” is rarely heard. Just as the role of director of feature films was once almost entirely focused on men, the music industry has also tended to be a realm of patriarchy.

There’s been a few exceptions and one of them is Patricia Chin. Aged 83 with 64 years experience, Chin has risen from stocking 78s on jukeboxes in rural Jamaican

bars to CEO of VP Records, the New York City-based operation that serves as the world’s foremost conglomerate of reggae/Caribbean record labels.

To celebrate this lifetime in the music industry Chin has a spectacular memoir out – Miss Pat: My Reggae Music Journey. Published as a hardback filled with photos of her, family and Jamaica’s foremost reggae artists, Miss Pat chronicles how a Kingston-born girl of Chinese-Indian parentage could marry Vincent Chin, another Jamaican-Chinese, in the late-1950s and together they would build an empire. Twice.

Unlike many a music biz memoir, Miss Pat is free of drugs and malice, instead being a celebration of her family and reggae. Vincent’s job was to travel Jamaica changing the 78s and 45s on jukeboxes “as the jukebox was the way most people heard their music back then,” says Chin when I call her in Queens, New York, where VP is based.

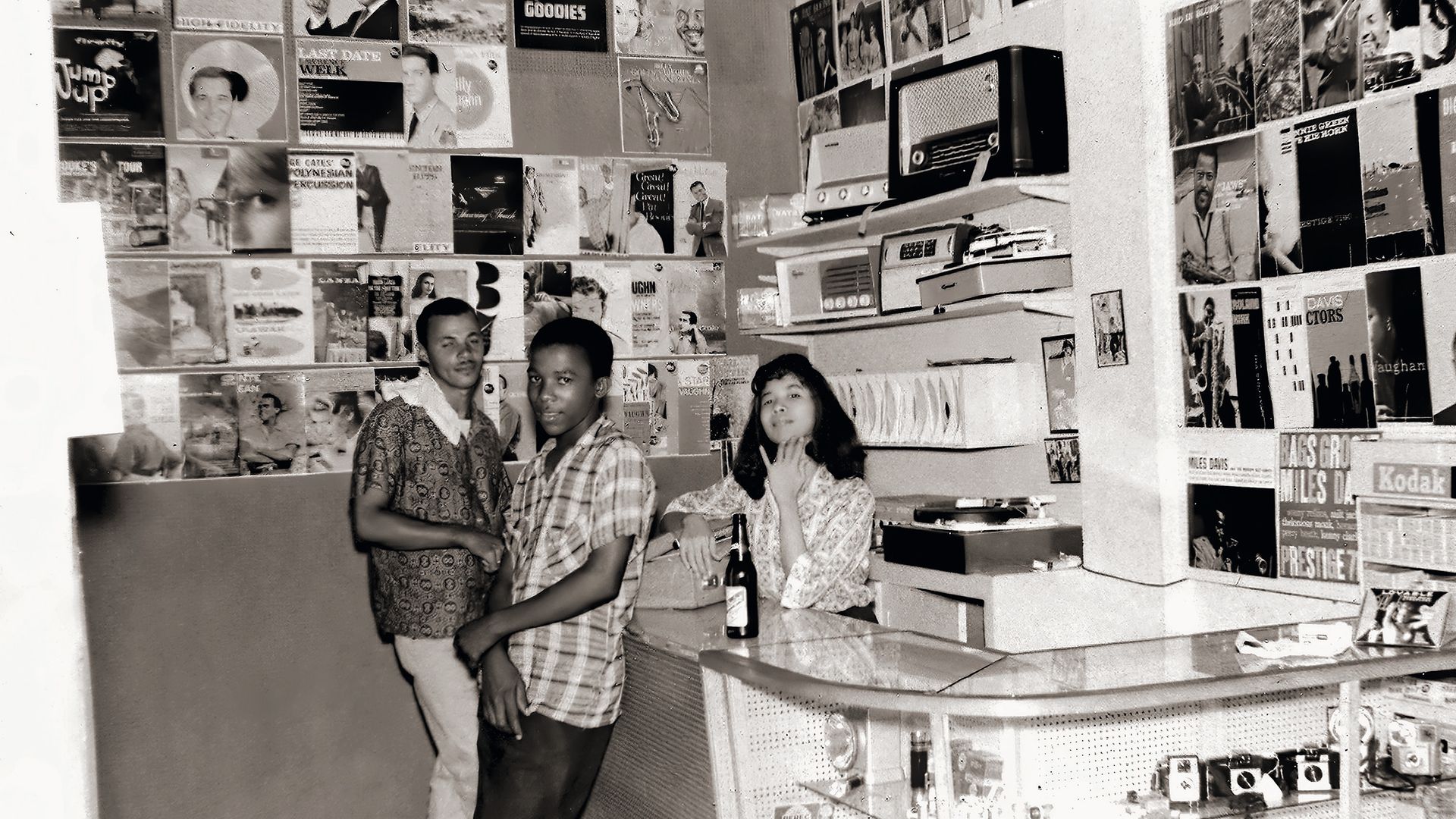

Patricia suggested to Vincent that he approach his employer, Joseph Issa (a prominent Syrian Jamaican entrepreneur), as to whether he could purchase the records no longer on the jukes and re-sell them. A deal was agreed and the couple set up Randy’s Record Mart – named after a Nashville radio show that played new R&B releases – a tiny shop that also sold sodas, soup and patties.

Immediately successful, the Chins’ shifted Randy’s to a bigger space, began selling new releases alongside used and, quickly ventured into recording and releasing local artists: with independence looming Vincent recorded the Trinidadian calypso singer Lord Creator singing Independent Jamaica in early 1962 and released it.

An early hit in a fledgling music industry – Jamaican artists had, somehow, never been recorded until the late-1950s – the Chins’ went on to run one of Jamaica’s foremost recording studios, operate myriad record labels, develop dozens of talented artists and build a family empire.

“Jamaica is so gifted with talented musicians,” says Chin when I enquire as to how Kingston appeared to explode with talent in the 1960s. “Once we started recording local artists everyone came to Randy’s. And when we opened Studio 17 above Randy’s we would be surrounded by musicians, often they would just hang around outside, hoping someone would need a keyboard player or a backing singer for a session.

“In Jamaica people love to dance and sing on the street and this is how I came to recognise talent. And by listening to what people wanted I began to understand what made a hit. I had my ears open and we played a role in ska and reggae taking shape.”

Amongst the myriad artists who regularly used Randy’s and Studio 17 was a young Bob Marley (“he was not how you see him today – Bob was very serious, focused, often he’d ask me if I’d seen his friend [prominent Jamaican footballer] Skilly Cole, as he loved to play football”), Peter Tosh, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, Niney the Observer and many others.

Other regular visitors were Chris Blackwell and Lee Gopthal, the London-based Jamaican entrepreneurs who founded Island and Trojan, the record labels that launched ska and reggae in the UK.

“They both drop by seeking new records to release, artists to sign, interested in who we had been recording. Britain was very important for us because there had been a big migration of Jamaican people to England so they created a market for us and then English people also came to love Jamaican music.

“We could make a record in Kingston and then, when released in England, it would be a hit before it had hit in Jamaica. We had a big hit in 1975 in UK with Fattie Bum Bum because UK DJs like to play it.”

While the 1970s should have been a gilded age for the Chins – reggae was winning an international audience – the deteriorating political situation in Jamaica forced the family to flee to New York. “Things just got too dangerous,” says Chin, “there was so much violence, riots on the street, kidnappings… Vincent went in 1975 to find us a place to live and I shut up Randy’s and followed in 1977.

“We had to start all over again. It was very hard as I had to say goodbye to all our friends and shutter the shop and studio and then, in New York, learn how this new country works, one where reggae was not very popular. It was a huge challenge.”

A huge challenge that the Chins arose to: they opened VP Record Retail on Jamaica Avenue in Queens and began distributing the releases of Jamaican and Trinidadian record labels to record shops in New York and beyond.

Then they began licensing Caribbean records and releasing them on VP – Vincent & Patricia – so slowly clawing out a market share. Ironically, it wasn’t reggae but its bastard offspring, dancehall, that established VP internationally.

Dancehall is an electronic Jamaican music that features a DJ chatting (rapping), often in strong patois, over an elemental electronic rhythm. While it developed

independently of rap – the Jamaican sound system is often thought to have provided NYC’s fledgling rap scene with its blueprint – it was a generation of African American rap fans who embraced dancehall.

By the 1990s VP were selling hundreds of thousands of CDs by the likes of Sean Paul, Lady Saw, Elephant Man, Beenie Man and others. As the label grew more successful VP began acquiring the catalogues of other Caribbean music labels, most notably purchasing the UK’s Greensleeves (a highly successful reggae

label that began in London in the early 1970s and continues as its own entity under VP’s umbrella today).

Even the decline of CD sales has not offset VP’s success with Chin noting that the combination of the vinyl revival and streaming revenues has ensured her label continues.

“I have been in the business since the days of the 78 and I’ve kept adapting to what the public wants,” Chin says merrily. “45s, LPs, CDs, now streaming and vinyl again, its all good. To my ears vinyl is the best but I learnt early on behind the counter of Randy’s that you give the public what they want so I’m happy to provide reggae music any way people want to hear it.”

Being a woman in such a male dominated world – and Kingston’s music industry is even more ruthless and macho than those in the UK or US – marked Chin as an outlier but she says she never gave her gender much thought.

“I had no choice – my husband was in the music business and we had babies so I had to work with him. Most of the people I’ve worked with have been men but I always deal with everyone in a friendly, honest way so I’ve never had any problems.” She then changes the subject, saying “back then no computers so I had to memorise everything in my head,” and laughs.

Chin’s story as told in Miss Pat is one of hard work and challenges being overcome. Its a shame she and the writers who helped her pen the memoir (there are four listed) didn’t press harder on what, at times, must have been some harrowing times.

Racial tensions and street crime in Kingston are ignored while her late husband’s struggles with alcoholism (he died of diabetes in 2003) is only hinted at. The murder of her grandson who, like many of her extended family, worked for VP but had returned to live in Kingston, is avoided.

Perhaps these absences are because Chin wishes her memoir to be a celebration of the happy times. She is widely honoured, receiving the Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Association of Independent Music, the Order of Distinction from the Jamaican government and tributes from everyone from Lee Perry and Chris Blackwell to BBC reggae presenter David Rodigan and reggae singer Marcia Griffiths.

Patricia Chin blazed a trail for Caribbean music – and for women in the music industry – and Miss Pat is a fitting tribute to her efforts. “I’ve still got my ears to the street,” she says when I ask how an octogenarian manages to run a record label making music for urban youth. “And I’ve got a community – and we are blessed.”

Miss Pat: My Reggae Music Journey is published by VP

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37