Few scandals have provided as vivid a cast of characters as Watergate. Yet the story often overlooks the one man without whom it would simply never have been detected.

Washington DC, 2.30am, June 17, 1972, and security guard Frank Wills is doing his rounds at the Watergate Building Complex. It’s been a quiet night. In fact, it’s been a pretty quiet year – in the 12 months since Wills took the job, the complex has been broken into only once, and then unsuccessfully. With dawn just around the corner, the young man is counting the hours until he can slope off to bed.

Then he notices something rather fishy.

Masking tape placed over a door latch. Clearly someone wants to keep this entry way open. His curiosity peaked, Wills removes the tape and makes a mental note to check the door again upon completing his next circuit.

Sure enough by the time Wills returns, fresh tape has been attached to the door. Once again, the security guard peels it off. This time, however, he calls for backup. With the police now on their way, our man walks through the door in pursuit of the tape’s owner.

So was triggered a chain of events that would culminate in the resignation of the American president and the imprisonment of his key advisors. As Watergate broke Richard Nixon, HR Halderman and – not quite all – the president’s men, it was the making of journalists Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.

With the covert assistance of FBI agent Mark Felt, the men from the Washington Post followed the breadcrumbs from the Democratic National Committee headquarters break-in all the way to the Oval Office. Somewhere along the way, however, the man whose vigilance meant there was a crime for ‘Woodstein’ to investigate fell out of the picture. And while he might have just been doing his job, without Frank Wills, America’s course could have veered in a very different direction.

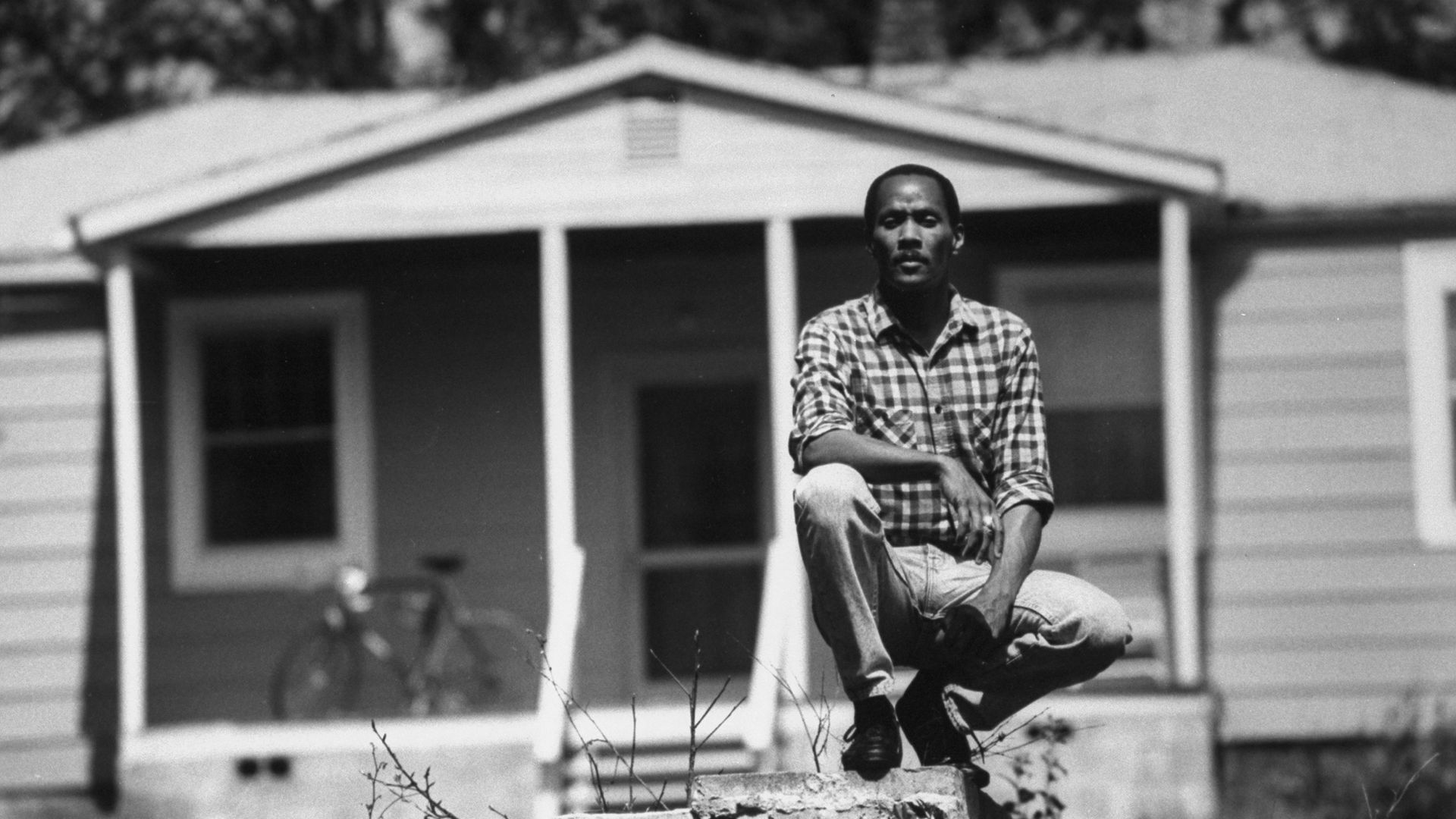

Until that summer’s night in 1972, nothing much about Wills’ life had been remarkable. Born in Savannah, Georgia, in 1948, he left school early only to earn an equivalency degree in heavy machine operations. From there he headed to Detroit’s assembly lines, accepting a position with Ford. Forced to quit the job on health grounds – he was a lifelong asthma sufferer – Willis relocated to the nation’s capital, picking up work at various hotels before the Watergate security gig became available.

As security work goes, the Watergate job was decidedly sedate. For proof of this, look no further than the fact that the guards didn’t carry firearms. Instead they would prowl the complex’s corridors wielding nothing more potent than a can of mace. Whether that would be enough to subdue intruders was something of a moot point since the Watergate was so rarely burgled. Consisting of exclusive apartments, a high-end hotel and some of the most coveted office space in the city, the worst crimes committed at the Watergate tended to involve the raiding of stationery cupboards and/or minibars.

All of which makes the events of June 17 all the more extraordinary. For after alerting the Second Precinct police to a suspected break-in, Wills and the local constabulary commenced a door-to-door search. With the cops having turned off the lifts and locked all the entrances to the Watergate, whomever was in there had no way of getting out.

What happened next is best explained by the man himself. “We found that the door to the Democrat National Committee headquarters had been broken into,” Wills told journalist Geraldo Rivera in 1974. “At that particular time, the police went in and they discovered some men behind a partition and they asked them to come out with their hands up.”

Of the five men arrested at the Watergate, three were born in Cuba. Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez and Bernard L Barker had all been involved in CIA-sponsored anti-Castro activities. The others were Americans who’d also worked for the Agency. James W McCord Jr was so respected by his fellow spooks that CIA director Allen Dulles had considered him “the best man we have.” As for Frank Sturgis, the Agency went to great lengths to deny that the veteran of the Pacific War had anything to do with their counter-intelligence operations in Castro’s Cuba; an announcement seen by many as confirmation that that’s precisely how Sturgis had been employed.

During police questioning, it was confirmed that the men had broken into the DNC headquarters to plant listening devices. For whom precisely remained uncertain, although the fact one of the burglars had upon his person the phone number of a certain E Howard Hunt set alarm bells ringing. A US intelligence veteran with links to everything from the Bay of Pigs to – if you believe Oliver Stone and his ilk – the assassination of John F Kennedy, Hunt was then freelancing for the White House Special Investigations Unit. Indeed, when the authorities phoned the number they’d chanced upon, Hunt himself picked up the call in his West Wing office. That he swore when the caller revealed their identity indicated that something was very rotten with the Nixon White House.

The fallout from Hunt’s fateful call will be familiar to anyone who’s read or watched All the President’s Men. Less well known is what became of Frank Wills after he walked in on the crime of the century. At first, his countrymen seemed keen to embrace him. Invited to appear on chat shows, Wills sat down with Mike Douglas and Geraldo Riviera and received a standing ovation on both occasions.

The Rivera interview revealed that, at the time of the break-in, Wills was making $80 a week. Promoted to sergeant of the guard in the wake of the arrests, Wills’ pay was also increased… by $2.50 a week.

Wills was later hired to play himself in All the President’s Men, for which he received a small fee and an invitation to attend the world premiere. It wasn’t much of a return for foiling so major a crime. And in the years to followed, he would have a hard time squaring what became of him with what had brought him into the public eye in the first place.

For while Woodward and Bernstein – deservedly – became household names and Richard Milhous Nixon had to familiarise himself with infamy, Wills headed to the unemployment line. According to the New York Times, he left his position at the Watergate after being offered so derisory a raise. Further stints of security work followed, together with a spell as a pitchman for a range of diet cuisine promoted by the trailblazing black comedian Dick Gregory.

The only job security Wills enjoyed was when he relocated to South Carolina to care for his gravely-ill mother. Not that the $450 social security cheque the pair had to live on each month went particularly far. With the cupboards bare, he took to shoplifting, a crime for which he was twice convicted, the second arrest leading to a 12-month prison sentence. When his mother passed away in 1993, he was so poverty-stricken, he donated her body to science as he couldn’t afford to bury her.

Wills himself would succumb to brain cancer in September 2000. He was just 52 when he passed away.

That Wills is remembered at all stems in large part from the world’s ongoing fascination with Watergate. Whenever there was a major anniversary relating to the crime and its outcome, you could be certain Wills would be wheeled out to talk about it. In 1992, when a reporter asked whether he’d do the same thing given his time over again, he replied: “That’s like asking me if I’d rather be white than black. It was just a part of my destiny.”

Twenty years after he helped bust Frank Sturgis and friends, Wills also expressed his annoyance that his role in the Watergate affair had been marginalised. As he told the Boston Globe, “I put my life on the line. I went out of my way…. If it wasn’t for me, Woodward and Bernstein would not have known anything about Watergate. This wasn’t finding a dollar under a couch somewhere.”

The difficulties Wills had with instant celebrity emerged soon after Nixon went into political exile. For example, when interviewed by Rivera in 1974, Wills regularly referred to himself in the third person; a trait common to sportsmen that indicates issues with both ego and insecurity.

The price society places on heroism also took its toll. “”Everybody tells me I’m some kind of hero, but I certainly don’t have any hard evidence,” he told the African-American journalist Simeon Booker in the mid-1970s. “I did what I was hired to do but still I feel a lot of folk don’t want to give me credit, that is, a chance to move upward in my job.” Indeed, the only things Wills had to show for his diligence were that measly pay raise and a truck given to him by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

But, the naysayers naysay, he was just doing his job, wasn’t he? Well, if it was just any old job, why is the security report Wills filed at 1.47am on June 17 now preserved in the National Archives?

As for precisely how Wills’ discovery should have been officially acknowledged, it’s fair to say that, while singer-songwriter Harry Nilsson’s decision to dedicate the 1973 LP A Little Touch Of Schmilsson in the Night to Wills was well-intentioned, it didn’t really do his feat justice. Nor, for that matter, did an award from the Democratic National Committee hit the spot; feeling less like a pat on the back for Wills than a raised finger in the direction of Richard Nixon.

Rather more fitting were the words of the Democrat South Carolina congressman James Mann who, while casting his vote to impeach the president said: “If there is no accountability, another president will feel free to do as he chooses. But the next time there may be no watchman in the night.”

However, it is perhaps Black History Month, which runs throughout February in the US, that offers the most fitting way to make sure Wills’ legend endures, and there have been attempts in recent years to use the month to make his story better known.

From forces of nature like Martin Luther King and Malcolm X to stars of stage, screen and the sports field, America isn’t short on larger-than-life black role models. Wills, however, was someone who did a job plenty of people would consider to be beneath them. As such, he’s as much an everyman as any man. The only difference being that, in doing that job to the best of his abilities, Frank Wills helped to bring down a president.

Whether as an advocate for the blue-collar work ethic or as the most relatable hero imaginable, Frank Wills has got it taped.

Watergate: The Final Score

If you’re unfamiliar with the fallout from Watergate, it’s nice to announce that this is one of those rare occasions where pretty much all the bad guys got their just desserts.

Frank Sturgis and his accomplices each served between 10 months and two years for burglary. Their paymasters E Howard Hunt and G Gordon Liddy served 33 months and four-and-a-half years respectively for masterminding the break-in.

Meanwhile, at the top of the tree, Nixon’s chief of staff HR Haldeman and chief aide John Ehrlichman were each sent down for 18 months having been found guilty of conspiracy to burgle, obstruction of justice and perjury. Attorney general John Mitchell – who’d quit that position to chair Nixon’s re-election campaign – served a similar term for lying under oath.

In all, 20 people were sentenced to jail for their role in carrying out or covering up Watergate. The name Richard Nixon might have been added to that number had not his successor Gerald Ford made it his first order of business to pardon the former president.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37