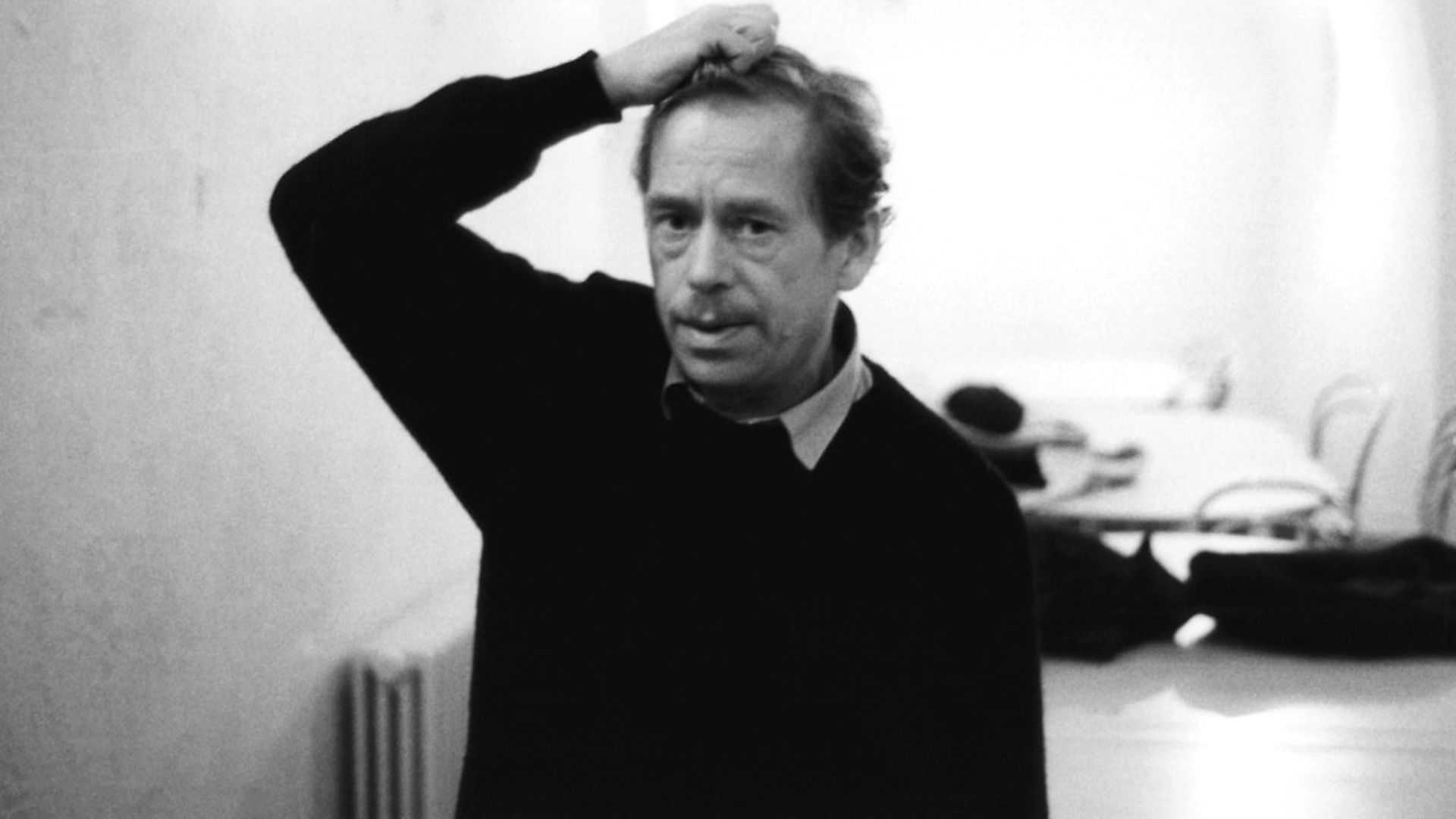

CHARLIE CONNELLY on the life of the last president of Czechoslovakia

Václav Havel was in a hurry in the early evening of March 21, 1990. He’d been president of Czechoslovakia for just under three months and this was the first full day of a state visit to Britain that was already behind schedule. After lunch with the Queen at Buckingham Palace, Havel had been driven to Downing Street for a meeting with the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, the length of which conspired with the London rush hour to prevent his arrival for a speaking engagement at the Institute for Contemporary Arts until the auditorium doors were already open.

As the audience for the event lined up ready to have their tickets checked they became aware of a car pulling up sharply outside, a door flinging open and a slightly anxious man in a blue blazer and red tie hurrying into the foyer. Václav Havel stopped, looked around briefly – and quietly joined the back of the queue.

He was soon whisked backstage but the incident shone a revealing light onto the character of the man who was arguably the most significant figure in late 20th century Europe. Havel was like nothing the continent had seen before in its leaders.

Here was a man who always appended a heart symbol to his signature but was far from a dreamy idealist, a man who would happily meet with monarchs and political leaders but at the beginning of one state visit lingered on an airport apron in the hope of meeting Mick Jagger. He was also a man who in order to negotiate the long corridors of Hradcany Castle, the seat of Czech power, bought himself a pair of roller skates.

If this makes him sound like some kind of wilful eccentric he was anything but. Havel was grounded, tenacious, dogged and principled, a dissident who through theatre and the political arena gave a voice to the voiceless and power to the powerless, who within the space of a few months in 1989 went from prison to the presidency. By turns bugged, followed, shunned and incarcerated by the communist regime Havel always refused their regular invitations to emigrate, determined to stay in Czechoslovakia in order to play his part in agitating against state oppression.

His experiences as a playwright and a political prisoner proved invaluable to his leadership of first Czechoslovakia then the Czech Republic, lending moral conviction to his politics and moral authority to his presence on the streets in the lead up to the fall of the communist regime, to his key role in negotiating the end of four decades of authoritarianism in a smooth and peaceful transition delivered in the space of a few short weeks without a single shot fired. Not for nothing was it dubbed the Velvet Revolution.

This moral authority also extended to his leadership, taking the wheel of a country that suddenly found itself free yet unsure of its immediate direction. As he told the audience that night at the ICA: ‘People have passed through a very dark tunnel at the end of which was a light of freedom. Unexpectedly they passed through the prison gates and found themselves in a square. They are now free and they don’t know where to go.’

Havel would serve 14 years as president, a role he assumed not through ambition but a sense of duty and desire to set a free Czechoslovakia on the best course to a prosperous, liberated future. That course would lead to him assuming the presidency of two entities: he resigned in July 1992 when Slovakia submitted its intention to declare independence as he was strongly in favour of retaining a federal Czechoslovakia, and then seven months later became the first president of the new Czech Republic. The division of the old country troubled Havel and underlined his own transition from philosophical advocate to pragmatic politician.

‘Putting into practice the ideals to which I have adhered all my life, which guided me in the dissident years, becomes much more difficult in practical politics,’ he said.

He learned lessons quickly, however, and established strong ties with the West. Havel set in motion the process by which the Czech Republic became a member of NATO in 1999 and the European Union in 2004, while expressing concerns that ‘the old European disease’ was still rife: ‘the tendency to make compromises with evil, to close one’s eyes to dictatorship, to practice a politics of appeasement.’

While he was unquestionably the people’s choice, Havel was happy to be his own man when it came to human rights policy. He was a vocal advocate for the rights of Roma, an unpopular standpoint among Czechs at the time, and also drew criticism when he set up a commission to inquire into the expulsion of three million Germans from the Sudetenland after the Second World War.

For all he was a man of the people, for the people and from the people, someone who had rallied and united an oppressed population against a totalitarian regime, Havel always felt like an outsider. Born into a wealthy family, his background was solidly bourgeois, his childhood featuring chauffeurs and domestic servants. When the communists assumed control in 1948 the Havel family became pariahs, their wealth revoked, their status a pejorative to the extent that Havel was prohibited from studying the arts and at 15 embarked instead on a four-year apprenticeship as a technician in a chemistry laboratory.

In the meantime he began writing, initially, he said, to explore his feelings of not fitting in. He eventually found work as a stagehand at Prague’s Theatre On The Balustrade in the early 1960s where his 1963 play The Garden Party, an absurdist tilt at government bureaucracy and a lament for the loss of individual identity, was performed for the first time. Similar works followed, notably Memorandum and The Increased Difficulty of Concentration, plays that went beyond mere entertainment to become beacons of hope. The Czech film director Milos Forman recalled how they penetrated ‘the hypocrisy and pomposity of the communist regime’ and ’emerged from the world of the stage to become a symbol of free thinking’.

The Prague Spring led to Havel attending performances of Memorandum in New York and London in 1968, but the Soviet crushing of the Dubcek regime led to the playwright being publicly vilified, banned from writing and forced into a job stacking empty beer barrels at a Prague brewery.

His political agitation continued, however. In 1977 he co-organised Charter 77, a group calling for the implementation of human rights guaranteed under international accords signed in Helsinki in 1975, a role that earned him three months in prison. Two years later he was arrested again, charged with subversion and this time sentenced to four-and-a-half years.

There were a further five months in prison in early 1989 for his role organising a demonstration but Havel’s release in May of that year proved to be a key moment in the collapse of communism in Czechoslovakia. In mid-November, a week after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the police brutally put down a demonstration in Prague, prompting Havel to set up the Magic Lantern theatre as a base for dissidents and establish the Civic Forum there, calling for the resignation of the cabinet and the release of all political prisoners. The following day he addressed a crowd approaching 300,000 in Wenceslas Square and the momentum for change had become unstoppable.

He was the first to admit that he wasn’t perfect – he drank and smoked heavily and had numerous extramarital affairs – but Václav Havel, calm, authoritative, clear-headed, determined and modest, was exactly the right man at exactly the right time for the Czechs and for the tumultuous Europe of the late 20th century.

‘When I get involved in something in my usual all-out manner I often find myself at the head of it before long,’ he wrote. ‘Not because I am cleverer or more ambitious than the rest but because I seem to get along with people, to be able to reconcile and unite them.’

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37