Of all the striking footballing images from this summer, quite a few have had no actual footballers in them.

There were photos of Boris Johnson in his England shirt at Wembley Stadium. Johnson standing on an absurdly vast St George’s flag outside Number 10. Priti Patel was also seen in an England shirt, before being criticised by Three Lions defender Tyrone Mings.

Never to be outdone when it comes to photo opportunities, Rishi Sunak was displaying his exuberant support for England in various forms. Unsurprisingly the need to be associated with sporting glory extends across the political spectrum. Keir Starmer, a genuine football fan and still a weekly five-a-side player, was photographed in his England shirt.

What would have happened had England won the tournament? Would the feelgood footballing factor have morphed with the vaccine rollout to give Johnson another boost in the polls? Would some Brexit voters have concluded that England was stronger alone, conquering those poor countries still incarcerated in the EU?

Political leaders at Westminster are convinced their fate is tied up with the England team specifically and football in general. They seek association with England’s successes and assume that triumph for the national team can lead to a government being seen in a sunnier light.

In his illuminating diaries, Alastair Campbell recounts the political mood after England’s defeat in the 1996 semi-final of the European Championships at Wembley. This was the summer before a general election.

John Major’s government was in deep trouble. Sitting near Major during the match, Campbell sensed the fragile prime minister aching

for an England victory.

Unlike Johnson, Major was a genuine football fan. Even so, Campbell assumed his mind was on other matters. The seemingly doomed prime minister was hoping for a euphoric victory that might lead to a joyful reprieve for his tottering administration.

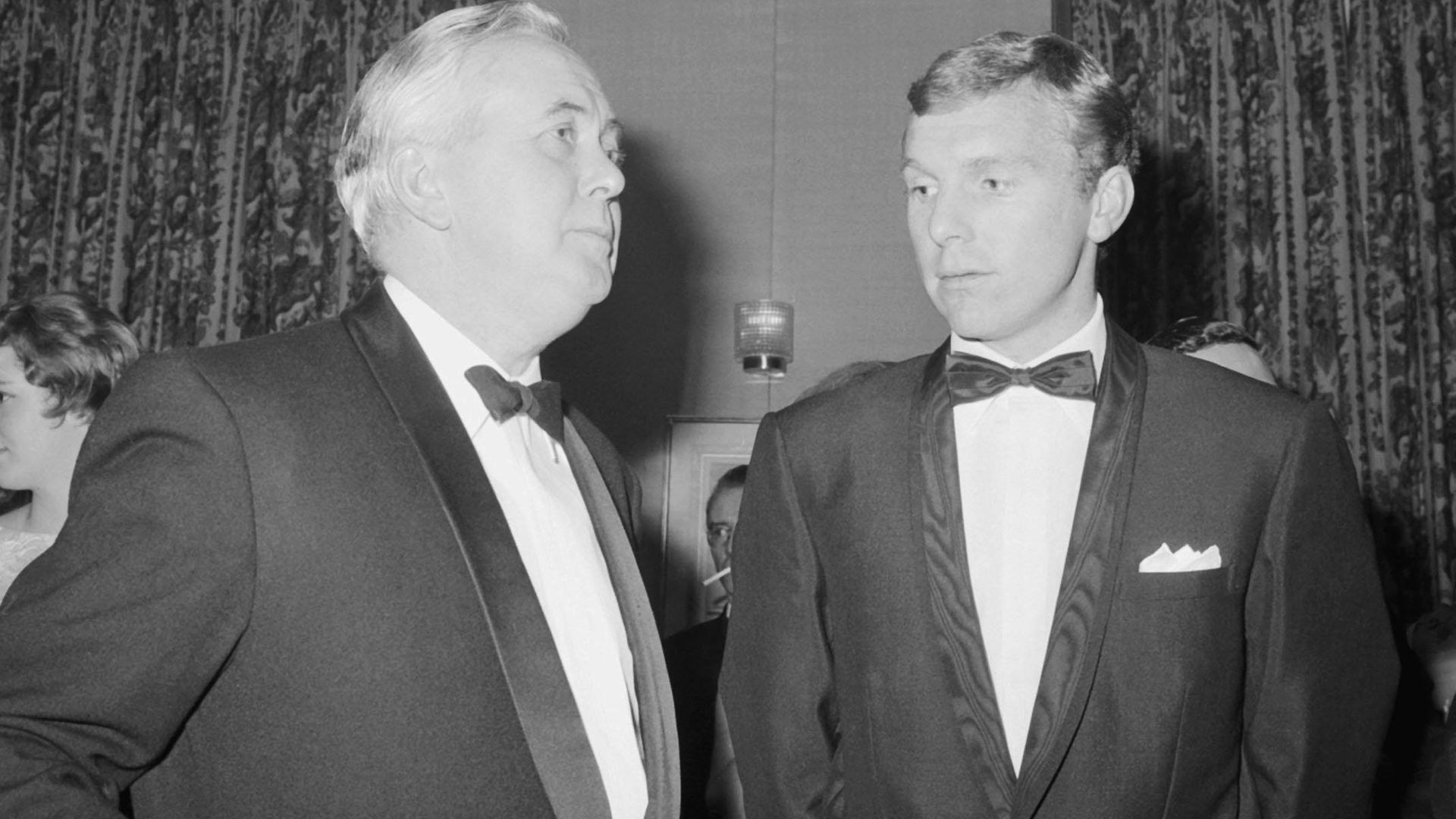

A lot of the modern assumptions about British politics can be traced back to Harold Wilson, oddly given that he has been more or less airbrushed out of history.

Wilson framed assumptions about the link between football and political fate, at least in terms of the passion with which the association is made. The late

Labour MP, Gerald Kaufman, once told me that Wilson “learnt to have a sense of humour”.

One of Wilson’s lines that got a laugh related to football: “Have you noticed that England only win World Cups under a Labour government?” It was a joke he was able to repeat on a regular basis, even if it fell flat in 1970.

Days before the election that year England were knocked out of the World Cup in Mexico, beaten by West Germany despite having been two-nil up. Unexpectedly Labour lost the election, the most traumatic event for Wilson in his long and stormy leadership.

He never fully recovered, even though he went on to win two more elections and a referendum on the UK’s membership of the then common market. Wilson wondered in his post-1970 gloom whether England’s defeat led to his bitter electoral defeat.

Ever since, prime ministers have felt the need to identify with football and the England team. As opposition leader, Tony Blair kept the ball up in the air impressively with Kevin Keegan. Gordon Brown, the most passionate football follower of any modern PM, agonised over what to say when England played Scotland while he was in Number 10.

David Cameron affected an enthusiasm for Aston Villa even though he mistook the team for fellow claret-and-blue wearers West Ham on one occasion. All would have yearned for the feelgood factor of this summer as England played some genuinely good football, at least up until the final, and conveyed a decent integrity.

Here is the twist. They will have yearned pointlessly. The link between football and a feelgood factor that translates into popularity for the government is a myth, or at most there is only a fleeting connection.

Wilson’s experience makes the point. He did win a big election victory in 1966, but that was before England won the World Cup. He lost in 1970 after the economic turmoil triggered by a devaluation in 1967, divisions within his government, and bad trade figures during the election campaign.

The England defeat would not have helped, but it was not pivotal. Wilson and Labour would almost certainly still have lost if England has beaten Germany and went on to win the World Cup in 1970. Edward Heath won, and he was not remotely interested in football.

If there were a significant feelgood factor linking football and politics there would presumably be a ‘feel bad factor’ when the England team is pretty useless.

That was the case in the 1980s when England failed to make much headway.

The failure did not stop Margaret Thatcher winning one landslide after another. Thatcher also felt less pressure to claim an ardent interest in football. Cameron’s relative indifference did not stop him beating Brown in 2010, a prime minister who could recite the Raith Rovers teams from the 1950s.

Jeremy Corbyn was a passionate Arsenal supporter. Keir Starmer is an Arsenal season ticket holder. Johnson has never been interested in football and yet is ahead in the polls, largely because of vaccines and not the performance of the England team.

There is no crossover, however tempting it is to assume there must be one. The proof can be discerned from another epic sporting event. In 2012 London staged the Olympic Games, seemingly a triumph of liberal internationalism on many different levels.

Four years later the UK voters to leave the EU largely on the basis of anti immigration parochialism. The mayor of London at the Olympics became the leader of the Brexit campaign. Thousands of columns have been written seeking to make sense of the contrast between the UK during the Games and what it became during and after the 2016 referendum.

There is nothing to make sense of. The UK hosted a successful global sporting event. Some voters supported Brexit on the grounds that they wanted fewer foreigners living in the UK.

Sport and politics do not connect. Even this summer, a lot of the fans who cheered on the England team were opposed to them taking the knee, including Johnson and Patel who refused to condemn the booing from some fans, to the disgust of Mings and pundit Gary Neville.

The fact that the team espouse some progressive values does not mean England becomes progressive. Football is an escape from politics, even if for England fans the escapism takes the agonising form of losing matches on penalties.

Steve Richards’ latest book is The Prime Ministers – Reflections on Leadership from Wilson to Johnson

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37