MARTYN SLOMAN on the furore over an advert which revealed an underlying political issue.

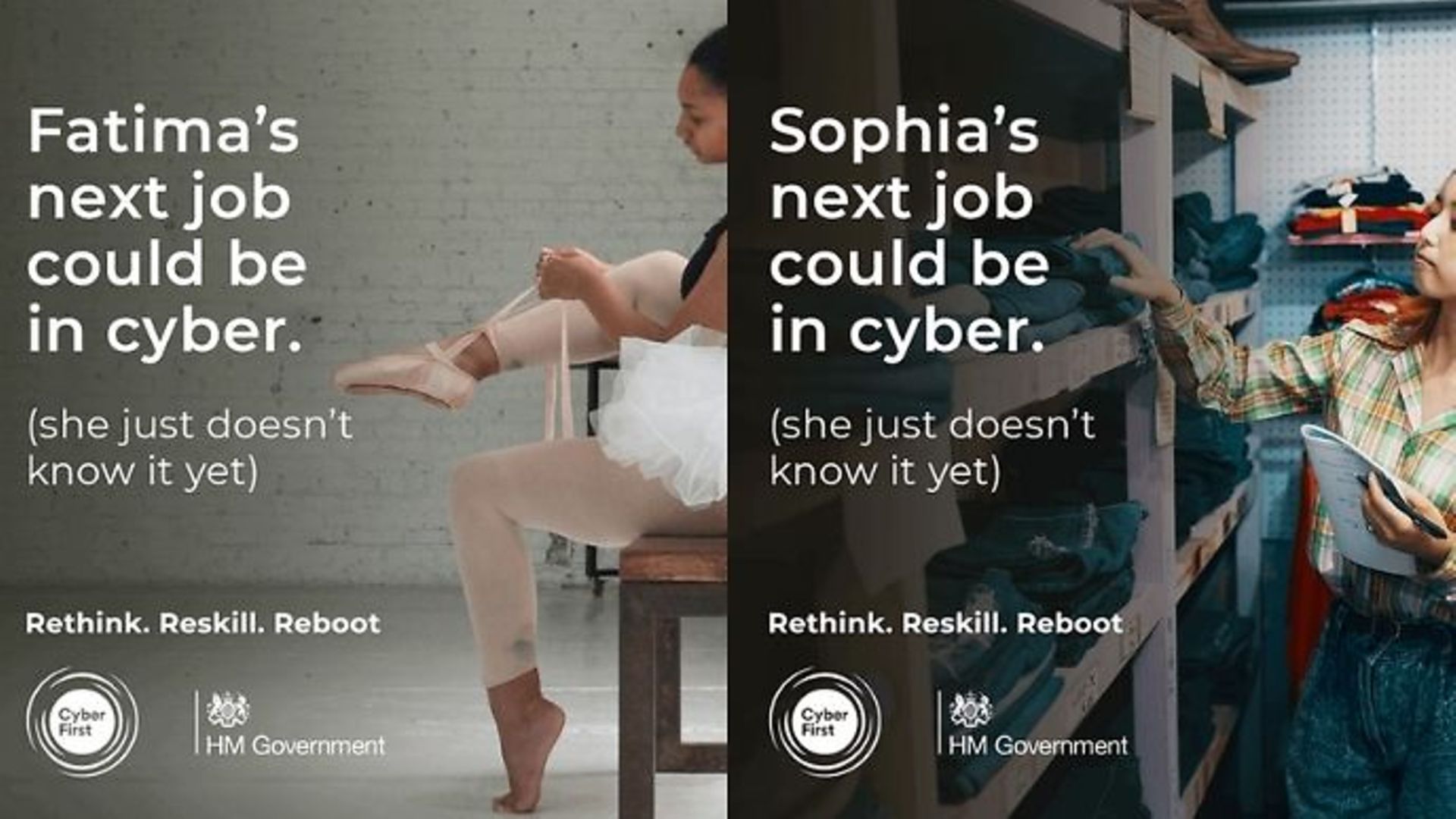

Rarely does an issue on skills training cause public controversy. There has however been a recent exception. A high-profile government-sponsored advertising campaign suggested that a young ballerina’s next job could be in cyber (“she just doesn’t know it yet!”). It was immediately withdrawn after Ministerial intervention: at a time when the performing arts are struggling to survive pandemic restrictions it was correctly described as crass by the Culture Minister. The advertisement will soon be forgotten, but it may mark the start of increased focus on what will unquestionably become a major political issue. This is the challenge facing skills training in a recession and the lack of entry opportunities for school-leavers.

This controversy over the advertisement surfaced in the week when my wife and I began our annual round of mentoring at our local Norfolk comprehensive school. There is an intake of about 100 pupils each year into Year 12 (the lower 6th). Early in the autumn term we run a series of one-hour workshops concentrating on skills and aspirations; the school then selects a dozen participants for individual guidance from us over the next two terms. We receive no payment but greatly enjoy the work and were delighted that the initiative went ahead as usual this year. Covid-19 restrictions, however, meant that the rooms were freezing cold because the windows had to remain open.

Over our five years of mentoring one powerful conclusion has emerged. It is the 50% who have not set their sights on university who face the greatest difficulties and present the biggest challenge.

A difficult situation is made worse by a continuous overstatement of the opportunities that are available and in particular a dishonest portrayal of the availability of apprenticeships.

In June this year, when the pandemic had already taken a firm hold, Prime Minister Boris Johnson stated that ‘we are going to have plans for work placements, supporting young people in jobs, apprenticeships, getting people into the workplace…’. The recommended search mechanism for apprenticeships is the Government’s ‘Find an apprenticeship’ site. If you insert the school’s postcode you get the following results for the availability of places within 40 miles: engineering five, IT nine, fashion zero. Indeed, for what it is worth, there are only twelve apprenticeships in fashion registered for the whole of England. Work experience placements in our North Norfolk hospitality sector are increasingly limited as businesses struggle to survive; travel abroad to gain a wider perspective has become impossible. It is a bleak prospect facing those who do not wish to continue to Higher Education.

So, could their next job be in ‘cyber’ as the advertising campaign optimistically suggested? True, IT security is a rapidly expanding area with growing employment opportunities: more and more people are using the internet for transactions, a trend considerably accelerated by lockdown, and cyber fraud is a lucrative area. I certainly recommend any students that I mentor who are considering studying IT to make sure that there are suitable modules on offer in the university of their choice. There will be. Inserting ‘cybersecurity’ into the search tool provided by UCAS (the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service) reveals 139 course from 57 providers. By contrast, inserting ‘cyber’ into ‘Find an apprenticeship’ uncovers 8 opportunities for the whole of England; only one of them is within 40 miles of the school and this is a chance to join the RAF police.

The message for today’s 17-year-olds could not be clearer: if you can, stay in full-time education.

All the above is the most visible and acute manifestation of a problem which has been with us for over a decade. Our political parties have tried to address what is seen as a skills problem by promoting apprenticeships; they have vied with each other to set arbitrary targets, harangued employers to deliver more places, and when this fails hand sums of money to consultancies to produce palatable figures by whatever means. None of this works.

Britain does not have a skills problem: it has an employment problem. There is a multi-faceted, structural problem in the UK economy which can only be rectified by a combination of macro and micro economic interventions over the long-term. It is more acute and more visible at the moment because employers of all sizes and in all locations cannot contemplate taking on any additional staff – let alone apprentices. They are simply struggling to survive and retain their current workforce through the pandemic.

Everybody bar the most extreme neo-liberal agrees that a Keynesian stimulus is essential. Only demand can protect jobs and firms will not invest in training unless they foresee demand. Moreover, it is impossible to predict the skills that an economy will need in the future, except in the broadest of terms. We can however ask that schools and colleges are clear on the basic skills that are needed and on what they can realistically impart. For that reason, I again cite the 2004 Tomlinson report which I discussed in a July article for this site. This put the case for reform concentrating on the 14-19 year old curriculum, but its statement of principles would apply through the education system: “learning programmes which combine the knowledge and skills everybody needs for participation in a full adult life with disciplines chosen by the learner to meet her/his own interests, aptitudes and ambitions”.

A first step in developing solutions will be an honest appraisal of the severity of the crisis we face today. Sadly, as all readers of The New European will be aware, Brexit, in whatever terms, can only exacerbate the problem. There is a huge challenge facing Keir Starmer’s Labour Party here, but surely an excellent opportunity to move away from slogans and hyper-promises, and demonstrate that the Party is indeed under new management.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37