Now that the Tory press is finally turning against Boris Johnson, the contrarian in me wants to start making excuses for his feckless, over-entitled incompetence. It’s not easy running a hand-picked second-rate government, you know. Not during the twin Brexit and Covid crises, only one of which is your own fault. Both your own fault if you count being unable to shake off a still-debilitating bout of Covid-19 linked to social non-distancing and obesity. Not easy at all.

Gosh, it’s hard work trying to make excuses for Boris, I’m already exhausted. Joe Biden has made clear his rejection of a US/UK trade deal which does not protect the Good Friday Agreement. And Amal Clooney resigned as a UK human rights envoy in protest at No 10’s cunning plan to exert pressure on EU negotiators by breaking international law, albeit only slightly.

Brexit hardliners were surprised and furious (“American interference”) but went quiet when Donald Trump’s special envoy to Northern Ireland, Mick Mulvaney (clue in name), issued a similar warning on the trade deal. By the time Theresa May explained her refusal to vote to break international law – unnecessary and unwise, as well as illegal – during Monday’s resumed Commons debate on the Internal Market Bill it barely made a ripple. Such is the corrosive effect of misrule.

But it also underlines the problem with being an “independent sovereign country” protecting its own interests in uncompromising ways. In a centrifugal world of populist nationalism, other independent sovereign countries do the same. Even those inside the EU, where they strive to compromise for the common good, they do it too. Currently they face stalemate over their budget and emergency Covid-19 rescue package, over sanctions against Belarus (human rights) and possibly Turkey, whose offshore gas disputes with Greece and Cyprus are looking ugly.

A fresh row with Istanbul threatens the EU-Turkey deal to curb refugees. A deal over gas extraction will enrage supporters of Europe’s green deal ambitions for carbon neutrality by 2050, if the planet hasn’t cooked by then. Who knew the world could be so complicated? Certainly not Boris the Columnist, accustomed to wrapping up most problems in 1,100 colourful words, ending in a joke. Governing is not campaigning or a column, it’s a hard slog. No wonder Keir Starmer used his virtual-Labour conference speech – made from red wall Doncaster – to say Boris “isn’t up to the job”.

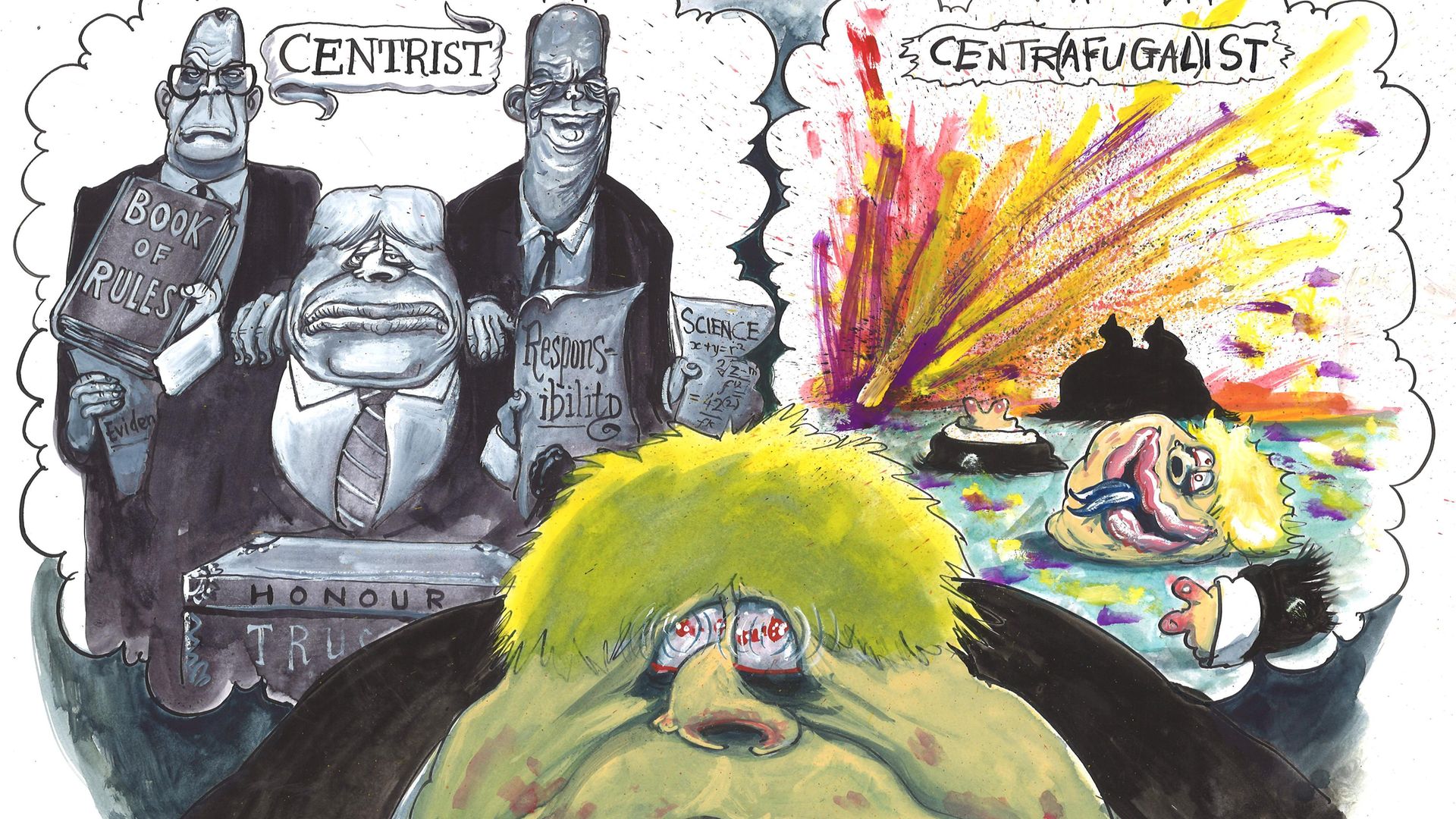

So recent days must have been very tough for him, forced to confront decisions on pandemic containment he knows will make him unpopular and go against his crowd-pleasing, Boris-pleasing nature. He dithered in March and knows he must not repeat the mistake as weekly infection rates double again. But right from the start it’s been written all over Johnson’s face that this prime minister doesn’t like asking people to obey the rules and be responsible, habits of “common sense and restraint” (copyright M Gove) he has preferred to avoid. He’s a fan of the mayor in Jaws, the one who kept the beaches open – pubs too, I expect.

When this PM says he’s not comfortable with a “snitch culture” we believe him. Remember how his noisy assault on girlfriend Carrie’s Camberwell sofa and other misdemeanours have been snitched all his life? Perhaps that is why Matt Hancock, his earnest health secretary, is an unloved target of Number 10’s bully briefers. The school prefect in Hancock didn’t hesitate to say that, sorry, but neighbours really ought to report those they see behaving selfishly because – as assorted infected skiers and pub crawlers have repeatedly demonstrated – spreaders can do exponential damage and kill granny.

For all his Tiggerish propensity to over-promise you sense that Hancock does care. He grasps that it might be his granny. On Sunday (on TV) and Monday (with MPs) Hancock was sent out to roll the pitch for the tightening of the “rule of six” regime which came in the PM’s Commons statement and broadcast on Tuesday. So were chief medical officer, professor Chris Witty, and chief scientific officer, Sir Patrick “Ricky” Vallance. Was theirs the first expert press conference without ministers at their side? No Boris-in-the-middle to jolly up their pessimism, muddle the message or palm off the awkward questions while claiming that “we’re following the science”.

In reality Team Johnson is not following the science, nor should it be. For one thing science is divided too – the permissive camp wanting constraints to be confined to the old and vulnerable, the collectivist majority stressing the medical futility of that approach. Political leadership is about balancing even larger equations. After listening to squabbling scientists, ministers must strive – courage in hands – to square it with what the economists, Treasury bean-counters and businesses, great and small, who are telling them about the cost of the pandemic, financial and human.

They must judge how best to keep public opinion disciplined enough to accept a winter of further restrictions with mostly good grace. The risks of rising Covid-19 deaths must be offset against avoidable cancer deaths and the toll which isolation takes on mental health. Non-Covid hospitals are being designated to help keep urgent operations running safely. Good. It’s part of the delicate trade-off which keeps schools, universities and jobs functioning, but closes pubs early and – smell of burning rubber – encourages us to work from home again. Surely, we can all get that? Perhaps not. Those data-driven policy changes are confusing.

We have spent much of the summer nostalgically celebrating – yet again – anniversaries of long-gone triumphs over Japan (1945) and the Luftwaffe (1940). Clergymen as well as politicians have made glib comparisons about the scale of sacrifices made by ordinary citizens then and now. The comparison is frivolous. In black-out Britain fear, hunger, the violent death of loved ones, the anxiety of invasion and blitz bombing in 1940, the last cruel horror of 3,000mph V2 rockets in 1944-45, all were incomparably worse. Death and injury levels not so different on the home front, homes were destroyed, but not jobs.

So times may be different, but people remain the same, for better as well as worse. The first lockdown – which covered VE Day – saw much made of the Blitz spirit. We were all in together. We all clapped for carers. But as new restrictions are introduced they seem to be increasingly contested – not necessarily by the opposition, but on the Conservative backbenches, and beyond. Much political goodwill has been frittered away over the summer by the government, particularly through failings over exams, and test and trace.

Going into the first lockdown, Britain could at least take some solace from the warming weather and the prospect of summer. Now, as we head into the autumn – with the next six months bringing the likelihood of a deepening, rather than an easing, of restrictions – optimism and stoicism could be harder to come by. There was a tetchiness in the first lockdown, but a widespread acceptance. This time around, there seems a more rancorous air in the wind. Boris has tried to consult devolved governments better – but new policy divergences have emerged this week – adding to the division and confusion, right though it may be.

Still, let’s seek out some optimism. Pollsters confirm that most voters still trust science – only a noisy minority prefer the anti-vaxxers and conspiracy theorists – as well as reinforcing anecdotal evidence of resurgent community spirit in countless ways. Apparently this is broadly true in most of Europe, but not the US where the Supreme Court vacancy caused by the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg has further inflamed a dangerously polarised society in election year.

Why not when Americans are famous for their ethos of self-reliance and community spirit? Partly, it’s caused by shocking and visible inequality. As Canada’s Dr Bonnie Henry, much-admired provincial health chief in British Columbia, shrewdly put it the other day: “We’re all in the same storm, but not in the same boat.” This is truer in the US than in most places, reinforced daily by TV pictures and a tangible feeling of rural and small town decay.

Secondly, the US has a demagogic president who now thinks his best way to secure re-election against the odds is to promote fear and division. In his way he’s on to something, as the populist regimes in Warsaw and Budapest also demonstrate – how best to restrain their illegalities is one cause of EU budget stalemate. Voters will usually choose order over disorder and the flag over abstract ideals, unless the argument is properly framed. That’s what Starmer sought to do in Doncaster. He also repeated “the debate between Leave and Remain is over. We are not going to be a party that keeps banging on about Brexit”.

You may passionately think he’s wrong. Realism suggests not – at least for the foreseeable future.

Leadership is the issue and Starmer knows he must not overplay his own hand on Brexit or Covid. That was evident in his emollient tone, responding to Johnson’s Commons statement on Tuesday. Likewise his SNP counterpart, Ian Blackford, and indeed the prime minister himself. Stern in his message but warning that worse may follow if the complacent minority (Boris using “complacent” as a criticism!) do not listen, the World King sounded more in control of himself and the situation than usual. Ditto his sub-Churchillian broadcast. He was notably polite to hacked-off Tory critics.

We should take comfort that Johnson is Trump tactician by expediency, not conviction. He is now aware of the narrow path he treads. His Tory libertarian allies, MPs, activists and economists, accuse him of authoritarianism over Covid-19 measures and demanding more parliamentary scrutiny in order to water down legal sanctions, marshals and punitive £10,000 fines that most can’t pay. Moderates and more experienced MPs want him to do whatever it takes and be fairer in whatever financial support Rishi Sunak produces to soften the blow for the neediest. Polls have Labour neck-and-neck (in England!)

In north-west towns like Bolton and on Tyne-and-Tees cash and curbs are linked. Plenty of voters think their local economies have been deliberately neglected – definitely not in the same boat as Belgravia or Teddington. Yet Preston has long pioneered a form of economic localism which pandemic restrictions have accidentally spread to other towns and suburbs with beneficial results. It is big city centres that are bleeding. Neglected voters are a prey to conspiracy theories that restrictions are just another punishment “they” inflict on “us”. No wonder Blackpool – exempted from the Lancashire’s regional lockdown in this week’s sunshine – was busier than for years with visitors in no mood to mask up.

In affluent West London an old(er) man in the park shouted at me to put my mask on the other day. He was 50 yards away, medically wrong too, but clearly meant well. So I thanked him instead of telling him to lose weight. Have you told someone to mask up on the bus yet? No, nor have I. A key worker was knocked down for doing so in the capital last week. But we’ll adjust to the now-familiar constraints as the new version of lockdown unfolds, hopefully one more localised and flexible than before. We have no alternative. “We must push down on the R,” is not Boris’s snappiest soundbite, but his options are restricted too. In the divided science community some claimed the new measures disguised a retreat towards a semi-Swedish permissiveness. Others say ‘too little, too late’ – again.

Winter is coming (doomed Dominic Cummings gets some things right) as we mark the equinox by reaching what Chris Witty calls “a turning point in the wrong sense”, more illness and death ahead. But so are most countries, even those which cover up or evade the truth. Where the British government remains an outlier is that the March lockdown was imposed too late and that the consequent economic hit has been more serious, both resulting in more social and economic harm. As chirpy economist, Tim Harford, points out, compound numbers can rapidly make a country feel poorer as GDP shrinks.

That’s why I persist in my belief that World King Boris will do a deal of sorts with the EU27. Brussels, Paris and Berlin’s anger against the threatened law-breaking has not been such that they have taken Michel Barnier’s bat away. He is still at the crease. A cross-party group of lawyers, pro- and anti-Brexit, have offered to devise a formula for solving Northern Ireland’s state aid problem. The UK is reported to be showing flexibility on fishing rights. Banks are moving key staff from the City to the 27 and shutting accounts of Brits living there. But the European Construction Bank has decided to stay. Good. Too much is at stake on both sides.

Under pressure from his own MPs, Boris is already backing off his initial stance on treaty-breaking and will present a climb-down in Brussels this autumn as a triumph, as he did last year. Whether or not the Tory press again goes along with that deceit against their readers in such circumstances would become a crucial question. It was “not an act of God,” Starmer reminded MPs.

In politics, as in life, many things are connected. The emerging consensus which could sink the pirate ship, Jolly Boris, in the months ahead, is that ministers failed to fix the test, trace and isolate system during the summer respite – failed to fix the roof when the sun was shining, as George Osborne was fond of falsely claiming. The rapidly escalating demand from real Covid-19 suspects (not just Matt Hancock’s “worried well” who always use more than their share of NHS resources) combined with seasonal illnesses shows signs of overwhelming a fragile regime.

Voters are getting wise to the distinctions between ‘capacity’ to test and tests offered, let alone actually done or diagnosed one way or the other in sufficient time. This looming threat of breakdown melds with another of Johnson’s many Achilles Heels: cronyism. Baroness Dido Harding’s claims to run the test and trace labs were shaky, but she has good connections. She is now going to run the revised Public Health England structure and is even mentioned as a successor to head of the entire NHS when Simon Stevens, a man steeped in 30 years of health management, steps down. And then there are those firms which got emergency Covid contracts without routine tender procedures, some of which have not done well. It doesn’t feel right.

When trust is crucial to successful management of public compliance with pandemic rules and a Brexit deal, these seemingly unrelated matters of probity may come to matter again. Tightening Covid-19 restrictions are a question of asserting “we” over “I” for the next few months and hoping for the best. The Camberwell sofa assailant is not the best placed leader to advocate self-sacrifice and less Friday night boozing. But he’s the only one we’ve got – for now.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37