From cannabis legalisation to festival drugs testing, European countries are shaping new, progressive drugs policies, and Britain risks being left behind

This July I had some illegal drugs tested at a music festival. I was told exactly how strong they were, given impartial advice on the best methods of imbibing them, and given the opportunity to surrender them. (I’ll let you decide whether I chose to.)

The testing was conducted by the drugs harm reduction organization, The Loop, at the Secret Garden Party with the approval of local police, and it felt revolutionary. It was a pragmatic response to rising numbers of ecstasy deaths, and was putting young lives before archaic British drugs legislation.

The Loop’s well publicized work over the summer, and the good-will it generated amongst the clubbing and festival going community was knocked out of the limelight by last month’s closure of Fabric after two ecstasy-related deaths on the premises. These two events occurred just months apart but sum up the schizophrenic nature of British drugs policy, which is at odds with the progressive drug strategies of our European neighbours. Whether its the blanket decriminalisation of Portugal or the Czech Republic, or the proposed advances in cannabis legislation in Germany and The Netherlands, the UK looks increasingly stuck in the dark ages of drugs reform.

‘This year there have been quite a few small steps forward, but some major jumps backwards,’ says George McBride, head of advocacy at Volte Face, a policy hub aiming to change the country’s legal approach to drugs from one of prohibition to pragmatism, harm reduction and (eventually) self-regulation.

In 2015 there were a record 2,479 drug-related deaths in England and Wales, up 10% from 2014, and our drug laws wilfully ignore the socio-economic and personal realities that inform both recreational and problematic drug use.

Volte Face are far from being a lone voice though. As examples of an ever broadening coalition of political support, McBride points to the recent cross-parliamentary report on the efficacy of medical cannabis, and the Liberal Democrats coming out in support of the regulation of cannabis. Tory MP Crispin Blunt also hit the headlines when he came out in support of a fully regulated drugs market and admitted to his own use of poppers.

On the other hand, 2016 saw the introduction of the misguided Psychoactive Substances Act in May. Conceived as a way to cut off the supply of so-called ‘legal highs’ by making their sale or production illegal, it mainly succeeded in turning them into a street commodity where the most vulnerable users can find them, and also created a keen market in prisons.

With the Brexit vote pushing drugs policy further down the agenda and a new Prime Minister with what McBride calls a ‘less than stellar history on drug policy,’ those campaigning for reform in the UK could be forgiven for casting covetous eyes towards our European neighbours.

In Germany they’re a matter of months away from legalising the purchase of medical cannabis. It’s been a long road to this point, with a number of organisations behind the Legalise campaign, not least Deutscher Hanfverband, a cannabis focused think tank. Georg Wurth of the organisation says that: ‘In 20 years [they] have seen a big shift in public opinion towards marijuana. Medical cannabis has a huge majority now with recent data suggesting 82% of Germans support it for medical purposes.’

Public opinion towards a formal legalisation finally swayed earlier this year when multiple sclerosis sufferer Michael Fischer ended a ten year battle, winning a landmark case enabling him to cultivate his own cannabis, and in May the German government approved a proposal to develop a national medical marijuana program. ‘I always thought we would win the battle,’ says Wurth. ‘Medical cannabis is just a question of humanity.’

This individual-focused approach also lies at the heart of Portugal’s trailblazing drugs policy. Implemented in 2001 as a reaction to the enormous problems enveloping the nation – an estimated 1% of its population were addicted to heroin – it decriminalised the possession of small amounts of all drugs.

Portugal’s problems were born out of a complicated history; nearly 50 years under the prohibitive dictatorial regime of Estado Novo meant the experimental countercultures of the sixties had passed them by. By the time Estado Novo collapsed in 1974 there’s was a nation ready, desperate, to let it all hang out.

‘We associated drug use with freedom,’ says Dr João Goulão. In 1998 Goulão was part of a board tasked with formulating a new drugs strategy for the country. ‘At the heart of the strategy was the reality that we were dealing with a health and social condition, rather than a criminal one.’

As well as providing syringe exchanges, treatment centres and methadone programs for heroin users, at the apex of the 2001 legislation was the implementation of ‘dissuasion panels’. If an individual is caught with an amount of drugs classified as personal use – classified as enough for ten days – they do not get a criminal record, but are sent to a panel where they are encouraged to reflect on the nature of their drug use.

‘The goal is to find difficulties you are facing that, when coexisting with drugs, could lead to problematic drug use; maybe your parents are divorcing, or you might be in conflict with your sexuality. You could then be offered an appointment to talk to a psychologist to support you. It is free and the decision is yours. Everything is anonymous.’

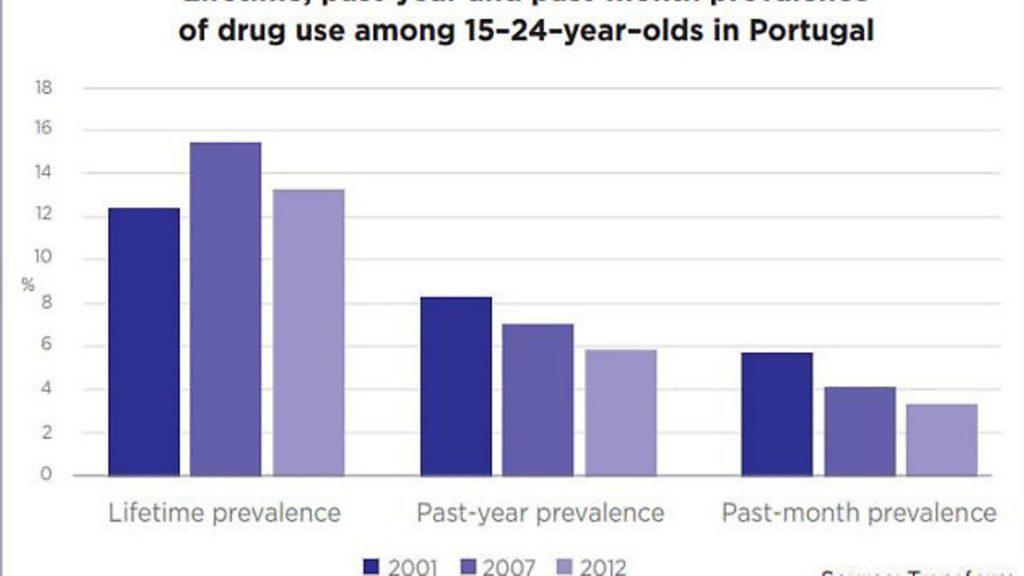

This kind of super holistic approach might seem like anathema to Theresa May and her right wing drug warriors, but the results speak for themselves. Portugal has a drug-induced death rate of just three per million people, as opposed to a 17.3 across the EU and 44.6 in the UK. The number of heroin addicts has halved to roughly 50,000, and drug use overall has declined across 15-24 year olds.

It’s not just Germany and Portugal that are lighting the path towards progressive drugs reform. Switzerland advocated a similarly humane reaction to its heroin epidemic of the late eighties; they’ve also got, in Dr Peter Gasser, the only person in the world that’s legally allowed to prescribe LSD. The Czech Republic, like Portugal, has decriminalised drugs for personal use and implemented a four point National Drug Policy Strategy based around the reduction of drug use and availability.

The Netherlands, as any teenager with an Interrail ticket in their back pocket will affirm, has long had a more tolerant attitude towards cannabis and soft drugs, and their wheels are slowly turning towards regulated marijuana cultivation.

Over the course of 2017, however, eyes will be mostly keenly trained across the Atlantic, at Uruguay, the United States and Canada. All are in various phases of new cannabis legalisation, with the latter due to fully legalise its recreational use next spring.

A huge marker for Canada’s drug future was laid when their Minister for Health, Jane Philpott, addressed the UNGASS (UN General Assembly Special Session on Drugs) conference in April and accepted that the country was not doing enough to help its citizens when it came to drugs. In her speech, she spoke of being inspired by a Canadian mother called Donna May who has been tirelessly campaigning for reform ever since her daughter, Jac, died of a heroin overdose.

May is part of Anyone’s Child; an inspirational worldwide network of bereaved families and friends who have lost loved ones to drugs. They are campaigning for drugs policy reform across the world, and stories like theirs are vital in framing the narrative for the populace and setting in motion the sort of public opinion swing that will propel politicians into action. Because for many people, record numbers of drug-related deaths are just a number, with festival drugs testing the sort of activity they would never engage in. But a mother losing their child? Anyone with a heart can empathise with that.

David Hillier is a Brighton-based writer, journalist and festival nerd. You’ll find him in The Guardian, Vice, Wonderland and tweeting @Gobshout

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37