ANDREW ADONIS explores the false power Brexiteers have over the blue passport row.

Of all the reasons for leaving the European Union, the pursuit of blue passports is the most ludicrous. These documents, first introduced just 99 years ago, only twice as far back as our EU membership, were originally written in French and used by a tiny number until we joined the EU.

Before then most Brits going abroad went to fight wars, mainly in Europe, and they didn’t need passports for that. Many of them never came back.

A certain type of Tory loves the passport because it smells of power. Particularly the opening injunction: “Her Britannic Majesty’s Secretary of State requests and requires in the Name of Her Majesty all those whom it may concern to allow the bearer to pass freely without let or hindrance, and to afford the bearer such assistance and protection as may be necessary.”

Before the 1950s this injunction came from the foreign secretary personally. I am just finishing a biography of Ernest Bevin, the great post-war holder of the office, and older people still say: “Ah I remember the passport which began: ‘We, Ernest Bevin…”

So be grateful for small mercies that it isn’t “We, Dominic Raab…” Worse, millions out there could be burdened with “We, Boris Johnson…”

It is all ludicrous, because Her Britannic Majesty’s Secretary of State cannot “request and require” free passage, still less any right to settle or do business, on the strength of the passport alone unless the country in question grants it. And many countries where Brits actually want to go to have granted this right, like Spain, France and Italy, have just withdrawn it because we are leaving the EU.

More numerically significant than the rights extended to Brits are rights which British and EU passports give or gave to people from overseas wishing to come to the UK.

Until 1962, the British passport enshrined a British citizenship which gave hundreds of millions of imperial subjects born abroad the right to visit, work and settle in the UK. This included my father who came from Cyprus with his British passport in 1959, a year before independence.

Because of the numbers involved, the British passport as a valuable commodity was systematically withdrawn from most of its holders just at the point they wanted to start using it.

For Brexit is the second time in living memory that a British government has sought to end ‘free movement’. The first was the 1960s when both Tory and Labour governments moved, controversially, to take this right away from people who were not only British or Commonwealth citizens but had fought for Britain in wars and served it in many other ways.

The reason for doing so could not have been more brutally stated. When introducing the Commonwealth Immigrants Act of 1968 which stripped most remaining citizenship rights from British subjects born abroad, Jim Callaghan, the Labour home secretary said this: “It would be irresponsible not to legislate on this vast issue of whether this country could afford in any circumstances to envisage the prospect of an invasion.”

These ‘invasion’ fears were similar, just less emotively put, to those of Enoch Powell in his “rivers of blood” speech made only weeks later. Nigel Farage and fellow travellers are in a long tradition of anti-immigrant politicians dating back to the anti-Jewish riots in the East End before the First World War.

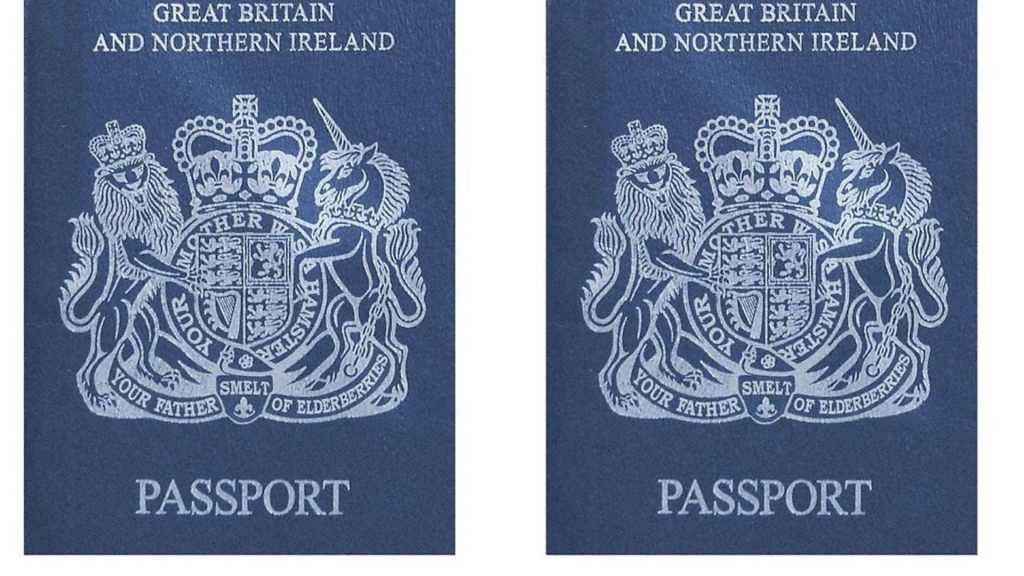

But what makes the current passport row so novel is that for the first time British-born passport holders are willingly destroying their own passport rights. They are being hoodwinked by older, and they think grander, passports which disguise the reality that in practical terms the blue document will be worth only a fraction of the previous one which had “European Union” at the top, before “Her Britannic Majesty’s Secretary of State”.

It won’t be long before nostalgia for the burgundy passports becomes near universal. Passports which did what passports were always intended to do: to enable you to travel, work and settle without further hassle in places you actually want to go. They were even written in English.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37