As an exhibition celebrates two British aviation breakthroughs, 50 and 100 years ago, Richard Holledge wonders what happened to the rate of progress and where the next giant leap might come.

Sunday June 15, 1919. The prayers of churchgoers in the Irish town of Clifden in Connemara were disturbed by the roar of an airplane. A rare event in those parts. As they watched a biplane swung to the south and landed slap bang into a bog, tail up, propeller firmly embedded.

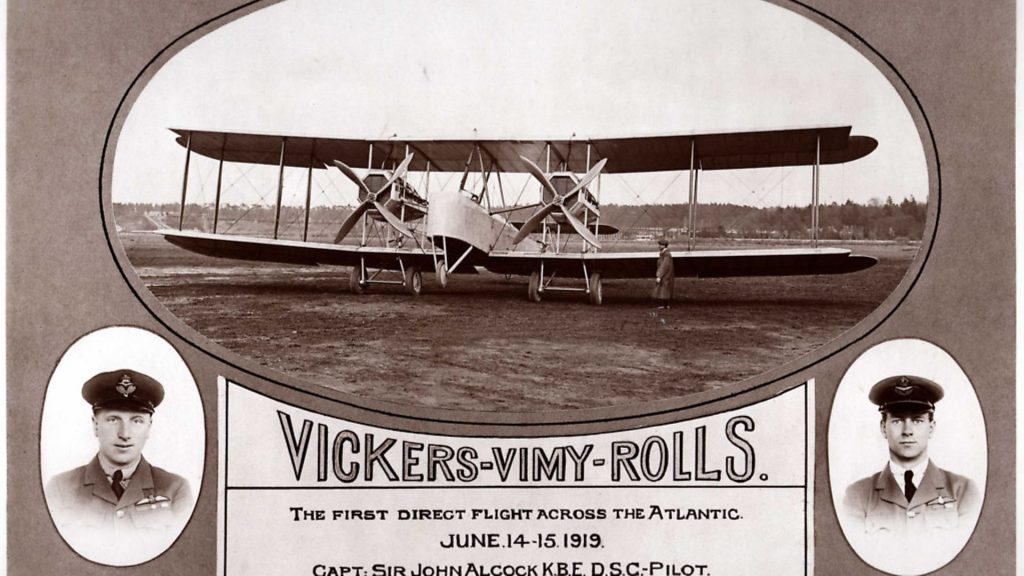

The pilots clambered out unscathed, introduced themselves as John Alcock and Arthur Brown and announced to the astonished crowd that they had completed the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic. It had taken them 15 hours 57 minutes to fly the 1,890 miles from St John’s in Newfoundland, Canada.

The success of those magnificent men and their flying machine 100 years ago is celebrated at the Brooklands Museum in Surrey with an exhibition, The First to the Fastest, which combines that anniversary with the maiden test flight of Concorde on March 2, 1969, 50 years ago this year.

The museum is able to draw on its own impressive history as the site of the nascent aviation industry with an array of memorabilia, photographs and artefacts, not to mention the airplanes themselves.

It was here that Alliott Verdon Roe became the first Briton to leave the ground in a biplane – albeit in “uncontrolled hops” rather than an actual flight. Years later Concorde, which was conceived and largely built at Brooklands, broke a passenger flight record by hopping to 68,000 feet.

It was at Brooklands that Alcock and Brown met after the First World War when they had both been pilots and both shot down and taken prisoner. By then the place had become a hub, maybe the hub, for eager engineers, dreamers and technological wizards to gather and develop the engineering advances made during the conflict to push the boundaries of automotive and aircraft possibilities.

That combination of high-powered thinking and cheery club-ability is reflected today; the Edwardian office building is reminiscent of a small town council building, wooden sheds, used by Malcolm Campbell in the 1920s and 1930s to design cars to beat the land speed record, are crammed with gleaming motors with more horse power than the Grand National. Twenties’ band music echoes around the site to keep the visitor in the mood. All that is missing is a chap with a cravat and a pipe to perfect the scene.

In 1919 the place was agog because the Daily Mail had decided to cheer up the war-worn nation by offering a prize of £10,000 – about £436,000 today – to the first people to fly the Atlantic in less than 72 hours.

The aircraft builder Vickers, which was based at Brooklands, had just the plane – the Vickers FB-27 Vimy bomber. By the standards of the day it was quite a beast with a wingspan of 67ft and two 12-cylinder 360 horsepower Rolls-Royce engines. Though it had been completed too late for the First World War it was designed to drop bombs on targets as far away as Berlin.

A replica of the plane is at the museum, which won plaudits last year as a finalist for the Art Fund Museum of the Year award, and what a spindly contraption it is. The front end looks like a tin bath, the fuselage seems too long and insubstantial to have carried bombs or the gasoline tanks which were installed in their place, fabric is stretched over timber frames, flimsy wings are held together and connected to the fuselage by struts and wires which look too thin to support the engines.

In March 1919, the plane was packed up in 13 crates and sailed across the Atlantic to Newfoundland where four rival teams had gathered. While Alcock and Brown re-assembled the plane in a large canvas tent and persuaded locals to clear a field of rocks to make it smooth enough for use as a runway, one competitor made a bid for glory, only to crash before becoming airborne. A second flew half way across the ocean before a radiator blocked and the aircraft was ditched at sea. Luckily the crew were rescued by a passing Danish steamship.

As another rival, the Handley Page team, dithered over a safety problem the Vickers duo seized their moment. They packed sandwiches and a flask of coffee each and at about 1.45pm on June 14 lurched down the runway barely missing the tops of the trees as they took off.

The flyers sat one behind the other in an open cockpit. They wore electrically-heated clothing (though the battery failed early on), Burberry overalls, fur gloves and fur-lined helmets.

A helter skelter of near disaster followed. With Alcock at the controls they battled through fog so thick Brown was unable to navigate using his sextant. They flew into a large snowstorm and were drenched by freezing rain. With the instruments icing up the plane went into a terrifying dive of more than 4,000 feet which Alcock managed to pull out of only 100ft above the waves.

They plodded on at about 106 mph until they crossed the Irish coast and saw the tall masts of the Marconi wireless station, which had been built in 1907 to connect with Newfoundland. Ironically, the flyers had refused to use a Marconi wireless because it was too new fangled.

Another irony; the Daily Mail, the race sponsor, missed their own exclusive. Despite having a reporter standing by for weeks, the editor of the Connacht Tribune got there first and broke the news.

The two men were feted and awarded the KBE by King George V. Their good fortune was not to continue. In December 1919, Alcock was killed in a crash as he was delivering the new Vickers Viking seaplane to the Paris Air Show. His partner Brown, who never flew again, died in 1948.

As the country basked in the achievement (Brooklands celebrated with a banquet which included ‘Oeufs pochés Alcock’, ‘Supreme de Sole à la Brown’ and ‘Gateau Grand Success’) all agreed that Britain ruled the air, particularly since an attempt to cross the Atlantic the same year by a US team had taken almost 36 hours over 23 days and involved four stops.

That sense of superiority was consolidated in the ensuing 50 years with the development by Vickers – later with Armstrong Whitworth – of civil craft such as the Vickers Vanguard, a 22-passenger twin-engined biplane which in the 1920s took about two and a half hours to fly from London to Paris.

The company also built racing planes – all the rage in the 1920s and 1930s – and the Second World War stalwarts, the Spitfire, the Hurricane and the Wellington bomber.

Post war, in the 1950s and 1960s the Vicker’s Viscount and the Vanguard were successful examples of British engineering while the V1000, based on the Valiant bomber, might have competed with American giants such as Boeing and McDonnell, but politics and economics intervened and it was cancelled at the prototype stage. So too was another trailblazing jet, the TSR2 bomber, whose training cockpit sits a little forlornly in the Brooklands hangar. Despite its sophistication, including a radar system 20 years ahead of its time, the project was scrapped in 1965 and instead the government bought the US F111.

The speed of development from the rickety Vimy to another advanced plane, the Vickers VC 10 of 1962, which even today holds the trans-Atlantic crossing record for a sub-sonic plane of five hours and one minute, is extraordinary, but even more improbable is the leap to the gleaming, super-sonic sophistication of Concorde which now stands on the Brooklands tarmac.

The development of rocket propulsion toward the end of the war saw the use of jet engines increase. A jet was even tried out in a converted Wellington bomber in 1946 and Avro converted the Valiant V bomber which carried nuclear warheads. The first purpose-built jet airliner was the de Havilland Comet, which first flew in 1949, so it was inevitable that thoughts should turn to building a supersonic airliner.

The first report into the feasibility of supersonic travel was made in April 1955 but years were spent deliberating over designs until in an early – if often scratchy – example of European cooperation the French, who had been working on their own version, agreed to join forces with Britain in November 1962.

From the Brooklands perspective there was much to be proud of. The front and rear fuselage sections and the tail fin were manufactured by the British Aircraft Corporation, which by then had subsumed Vickers, and the museum can boast that their Concorde was the first aeroplane to carry 100 passengers in supersonic flight in 1974.

Just as Alcock and Brown had brought pride to a war-torn country it must have felt that once again Britain (and France) were leading the way in the travel of the future, particularly in a year which saw the first flight of a Harrier jump jet.

Concorde undoubtedly captured the imagination but at a price – the cost of building rose from the forecast £70 million to £1.3 billion and despite interest from 74 companies only 20 aircraft were built, including six prototypes and development aircraft, leaving Air France and British Airways to buy the remaining 14.

Sales were stymied by the stock market crash and oil crisis in 1973, but above all by the cacophony of the sonic boom which aroused such opposition that flights were restricted to ocean-crossing routes only.

With all the patriotic tub-thumping it had perhaps been understandable to overlook the launch of another airplane one month before the first Concorde test flight – the Boeing 747. Slower, of course, but cheaper and more economical – and still flying.

The problem was that Concorde had put prestige over efficiency. It could barely fly from the UK to US east coast and could not reach the west coast. The aircraft had a total passenger capacity of 100 but consumed the same amount of fuel as a Boeing 747, which could fly twice as far and had four times the passenger capacity.

Even as Concorde flew its first passengers in 1976 its business plan was out of date and, in fact, it probably should have been grounded in the 1980s because by the 1970s the demand was for cheap, not super fast, travel. In the 1990s and into this century the call has been for more environmentally friendly craft not one that consumes 25,625 litres of fuel per hour as Concorde did.

Above all, there was no way UK manufacturers could compete with the sheer economic power of the US which could produce hundreds more planes more cheaply and by the time of Concorde’s demise the UK was reduced to making the wings for the European-based Airbus consortium which, despite considerable success, lagged behind Boeing in 2018 with orders for 747 aircraft while the US rival had won 893.

As for supersonic travel, periodically some visionary produces a blue print for a new, improved Concorde. The rocket-powered Hotol, was envisaged to hit Mach 5.0 – Mach 6.0 (3,800mph to 4,500mph) but the government withdrew funding in 1986 after four years work.

Only last month Oxfordshire-based Boom Technologies claimed that improvements in engines, fuel storage, aerodynamics and materials will enable a space plane to fly at 25 times the speed of sound – that’s London to New York in one hour.

To boldly go as fast as possible is still seductive. That is part of the reason so many mourned Concorde’s going. Actress Joan Collins, who rumour had it travelled free in exchange for posing up every time she took a flight, damned the end of Concorde as a “travesty of civilisation” and the plane’s first test pilot Brian Trubshaw asserted: “It is not unreasonable to look upon Concorde as a miracle.”

But when it comes to assessing miracles it is hard to match John Alcock’s splendidly understated, very British, remark after he had jumped from the wreck of the Vimy: “Yesterday I was in America. I am the first man in Europe to say that.”

The First to the Fastest is at Brooklands Museum, near Weybridge, Surrey. The museum is staging a series of projects and displays over the next two years

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37