With this year’s European Championships another victim of the coronavirus, MICK O’HARE looks back on the first ever tournament – 60 years ago this summer – another contest overshadowed by off-field events

When Marcel Rosenberg arrived in Madrid in late August 1936 to take up his short-lived post as the Soviet Union’s ambassador to the Second Spanish Republic – bringing with him a pledge to supply arms and support in the fight against Franco – he had no idea that among the momentous consequences of his mission would be the inadvertent help it would provide his country in winning the first ever European football championship, some 24 years later.

Of course, none of those behind the new tournament, which reached its climax in Paris in July 1960, had intended for the competition to be used as a vehicle for politicking and for the playing out of some of the 20th century’s rawest geopolitical rivalries.

On the contrary, UEFA – which had only been established six years earlier – had hoped that sport would help to bring the troubled continent together. But with the Cold War in one of its most volatile phases, and unsettled scores from older conflicts still festering, there was little chance of that.

There will, of course, be no 60th anniversary European Championships this year – coronavirus has settled that – but when it is held it will be in a different format to recent tournaments, with games played in 12 host cities, in 12 countries. This change was introduced for 2020, in part to mark the anniversary of that first contest, when the tournament was decidedly decentralised.

Indeed, not only did the often cantankerous 1960 Euros not take place in just one country, they didn’t take place in just one year. The tournament actually kicked off in 1958, with a series of rounds culminating in the semi finals and finals held in the summer of 1960.

It was a knock-out contest, with countries drawn against each other playing two legged-ties, with matches at home and away. Seventeen nations entered, with notable absences from West Germany, Italy, England and the Netherlands. To even the numbers out, the Republic of Ireland and Czechoslovakia were selected to play a preliminary tie, with the latter going through to the round of 16.

Little over a decade on from the end of the Second World War, and with the Cold War exerting a distinct chill, there was plenty of potential for incendiary clashes among the teams taking part. But in the end, the first round draw was kind and kept foes apart – with one notable exception. This was the one that pitted the USSR against Hungary.

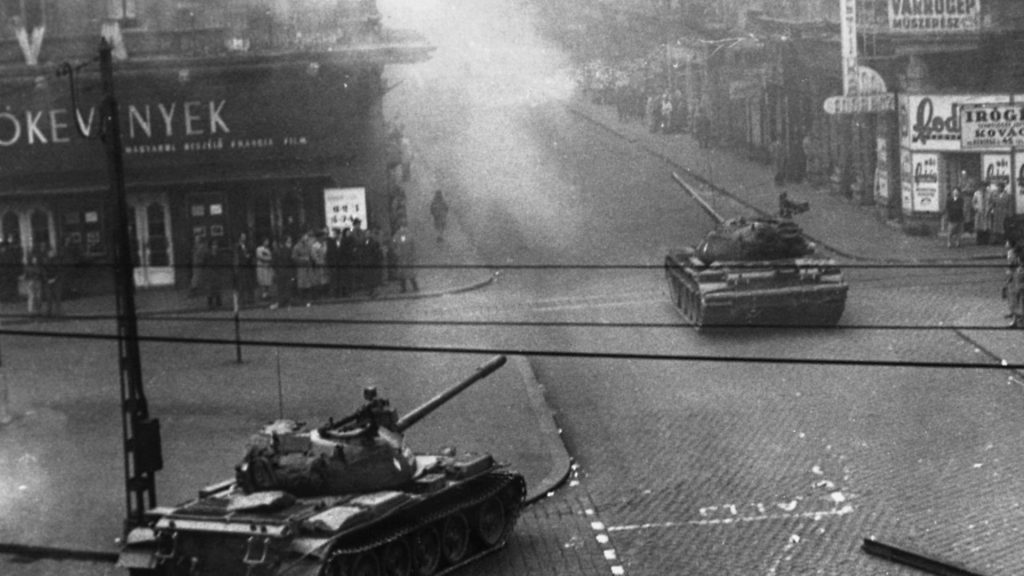

Just four years earlier, a student revolt against the Soviet-backed Hungarian regime had grown into a nationwide rebellion against the one-party, communist government of Imre Nagy. Nagy had been seen as a liberal reformist in contrast to his predecessor and ‘Stalin’s man in Hungary’ Mátyás Rákosi.

Faced with waves of protest, Nagy was pragmatic, dismantling the state secret police, promising free elections and planning to withdraw from the Soviet-controlled Warsaw Pact military alliance. It was too much for Moscow. Premier Nikita Khrushchev sent in his troops on November 4, 1956, occupying Budapest and other Hungarian cities.

When the fighting stopped six days later, 2,500 Hungarians were dead (along with 700 Soviet soldiers). Many more would be imprisoned or executed and 200,000 fled to Western Europe and elsewhere, as Moscow re-asserted its dominance over the country.

Beating the Soviet Union on the sports field was the only form of revenge Hungarians could exact. And there was a notorious sporting precedent. On December 6, 1956, mere days after the invasion, the USSR and Hungary had met in the semi-final round of the water polo competition at the Melbourne Olympics. That contest has achieved fabled status, not least in Hungary, where it is known as the Blood in the Water Match. The Hungarians had prevailed in an extraordinarily brutal contest, and gone on to win the gold medal.

Now, the country – a major footballing power at the time, having got to two World Cup finals – had another chance. More than 100,000 people watched the first leg in Moscow in September 1958 and the Hungarians, realising it might not be wise to resort to aggressive tactics while in the capital of their occupiers, attempted to play defensively, hoping to take a low scoreline back to Budapest for the return match.

It backfired. The Russians were relentless and won 3-1. A year later in the second leg the Hungarians, a skilful team with a fine if diminishing reputation, went at it hammer and tongs.

Unlike their water polo counterparts they wanted to win playing football rather than maiming their opponents, but over-exuberance and desperation to succeed got the better of them. Chances were spurned, mistakes aplenty were made and Russia took advantage to score the single goal that won the match.

‘We should have played our normal strategic game,’ said Hungarian midfielder László Budai. ‘Instead we thought we had to throw everything at them and that just left our defence exposed. We felt dreadful letting down our supporters and our country. We could have made the world seem a better place for one evening.’

The Soviet victory lined up a quarter final tie that would see even older historical tensions revived, as the tournament reached its pivotal moment, and the consequences of Marcel Rosenberg’s 1936 mission to Madrid were finally played out.

Again, the draw was relatively benign, in keeping adversaries apart. France took on Austria, while Yugoslavia were drawn against Portugal, and Czechoslovakia faced Romania. But, again, it was the tie involving the USSR – very adept at amassing adversaries – which provided the controversy. The Soviets had been drawn against Spain. And here was a problem.

Franco had neither forgotten nor forgiven the Soviet Union for the support for his republican foes during the civil war that had followed in the wake of Rosenberg’s arrival in Madrid, and the football tie presented him with a dilemma.

The general was a football fan – possibly as a matter of expediency and one with ulterior motives – but nonetheless once won over he took it very seriously, to the point of petty indignation. His team was Real (or ‘Royal’) Madrid. The club still play at the Santiago Bernabéu Stadium – named after the former player and club president who fought for the Nationalists in the civil war. And Franco was determined they would win. Everything.

Their rivals were then, as now, Barcelona – the city that had held out the Nationalists for almost three years and represented a bastion of Catalonian separatism. Franco’s troops had killed the Barcelona club president Josep Sunyol in 1936 and he had imprisoned, threatened and exiled many players from the club and those of other rival teams such as Athletic Bilbao, supported by Basque separatists who had also fought Franco. He had insisted they change their club names and crests to become more ‘Spanish’.

By the end of the 1950s, his country was a powerful force in European football. His team, Real Madrid, had won every single European Cup since it was established in 1955, and the national side had triumphed 7-2 against Poland in the first round of the European championships to secure the tie against the Soviets.

The Spanish side included several outstanding players, most notably Alfredo di Stefano, Luis Suarez and Laszlo Kubala, and were among the favourites to not just progress to the next round, but win the entire tournament.

Yet Franco was both vindictive and a coward. And as much as he loved football and its power to cement his regime, he also feared for its potential to weaken it, and to humiliate him. This was the risk presented by the two-legged tie against the Soviets, and in the end he simply refused to let his team play.

Ostensibly the Spanish government argued its players would not be safe travelling to the Soviet Union for the first leg, but privately Franco would not permit Spaniards to fraternise with communists, in part because they might lose, but also because he believed that players whom the public admired might return from the USSR with ‘malign and degenerate political beliefs’ which could infect the Spanish population. He is also said to have objected to tournament rules that dictated that the USSR’s hammer and sickle flag would have be flown and its national anthem played when the team visited the Santiago Bernabéu Stadium. He was concerned that the Soviet team’s presence in his country might provoke some display of public support from those among his own population who had fought alongside the communists against his forces just over two decades earlier.

Franco was all to aware that the ghosts of that era had not been laid to rest and the Soviets had the ability to raise them.

According to some reports, it was the home leg that really troubled him. There are claims that the Spaniards offered to play in Moscow but wanted to move their home leg to a neutral venue, only for UEFA to refuse.

Despite the wrangling, there had been hopes that the games might go ahead. The USSR devoted considerable resources to preparing their players. Their domestic league was out of season, so the national team headed to central Europe to take on a series of club sides, before returning to their base at a resort usually reserved for senior officials.

Their final warm up game was a 7-1 thrashing of the Poles which was watched by officials from Spain. It may have been at this point that Franco to call the whole thing off.

In the end, the Spanish players were only told of the decision on May 25, 1960, two days before they were supposed to travel to Moscow. Di Stefano, who had already missed out on successive World Cups, is said to have reacted angrily to the news but Federation president, Alfonso de la Fuente Chaos told him simply that there were ‘orders from above. Franco said no’.

‘At the time I was furious,’ said former Spanish-Basque defender Jesús Garay, a player with Barcelona but born in Bilbao. ‘I just wanted to play and to hell with Franco’s politics. He robbed me of my chance to win a championship.’

Notices appeared in the Spanish newspapers the following day, but the entire affair was quickly and quietly forgotten in the country. Not so in the USSR, where propagandists made sure to get plenty of political capital out of Franco’s churlish decision.

The real benefit for the Soviet Union, though, was the sporting reward it reaped as a result. The team was handed a walkover which meant that, against all the odds, it was through to the finals stage of the tournament, to be held in France.

Over the course of four days, two semi finals were to be played, before the dreaded third place play-off, and then the final, at the Parc des Princes. Helpfully, for those Soviet propagandists, three of the four teams to have qualified were communist: the USSR, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, with France the only western nation.

In the semi final, the Soviets were, for the first time, drawn against a country with which they not no particular grudge, Czechoslovakia. Of course, that was to change eight years later, when Soviet troops and tanks occupied Prague in order to crush reformist Czechoslovak leader Alexander Dubcek’s liberalising Prague Spring.

But in 1960, at least superficially, the two nations were fraternal allies. There may be no truth to the rumour that the Czechoslovaks were ordered to take it easy and not upset their bigger brother on whom they relied economically and militarily, but the USSR won the semi final effortlessly, triumphing 3-0 at the Stade Vélodrome in Marseille.

With the hosts France unexpectedly losing their semi-final against Yugoslavia, 5-4 at the Parc des Prince, however, the final game would throw up another intriguing political mismatch.

Although the Soviets would be playing yet another socialist nation in the only all-communist international football final ever played outside the Olympic Games (which, until relatively recently, only allowed amateur players), this one was unlikely to be as compliant as the Czechs.

Josip Tito’s Yugoslavia was a key member of the Non-Aligned Movement along with other nations such as Cuba and India who were all – ostensibly at least – neutral in the Cold War. The movement had been founded in Yugoslavia in 1956 and although the nation itself was a single-party socialist state it refused to be part of the Warsaw Pact and was only an associate member of COMECON, the socialist economic bloc effectively controlled by Moscow.

The Soviet hierarchy had long regarded Tito as a renegade, and the feeling of disdain was somewhat mutual. Both wanted to get one over on the other and a football field was as good a place as any.

For once – on neutral territory – the match was played in an open, flowing style, the best of the tournament so far. Sadly, because France had been eliminated, only 17,966 turned up at Parc des Princes, but those absent missed Yugoslavia taking the game to the Russians.

They were totally dominant throughout the first half but Russia’s talismanic Lev Yashin, the only goalkeeper ever to win the Ballon d’Or as international player of the year, restricted them to a single 41st minute goal from Milan Galic. It was, however, the clichéd game of two halves. Slava Metreveli equalised almost from the restart and although the Soviets pressed forward relentlessly the game went into extra time. Their dominance continued and with seven minutes remaining Viktor Ponedelnik scored their winner to confirm a most improbable success.

Of the 17 countries who had entered that first championship Spain and Hungary, to name just two, were both deemed far more likely victors. But the Soviet Union’s route to the final rounds, with each subsequent round pairing them with ever-more politically provocative opposition, can perhaps be described as fortuitous, and certainly intriguing.

Of course, neither nation which competed in the final that day still exists, and it was the only football title the USSR ever won outside the Olympics. How much of it came down to the international political situation the country had crafted for itself is up for argument. What cannot be denied is that, in the end, they were worthy winners. And the final irony? At the next championships held in Spain in 1964 (the format was the same, although 29 countries entered) the host nation met the Soviet Union in the final in Madrid. Spain would win 2-1. Sadly for him, Jesús Garay had retired from international football, but guess who did bother to turn up?

HENRI DELAUNAY

The winner of the European Championship receives the Henri Delaunay Trophy named after the French football administrator instrumental in the inauguration of the competition back in the 1950s when he was general secretary of UEFA. Delaunay, however, has two stranger claims to his name. He began his off-field football career as a referee until he was struck in the face by a ball causing him to swallow his whistle and nearly die. He then turned to administration and was an architect of football’s World Cup. He was one of only two people aware of the location of the competition’s Jules Rimet Trophy during the Second World War after he advised Italian counterpart Ottorino Barassi to hide it. The trophy was in Italy’s possession after they won the 1938 World Cup. It remained undiscovered in a shoebox under Barrasi’s bed until the war ended in 1945.o

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37