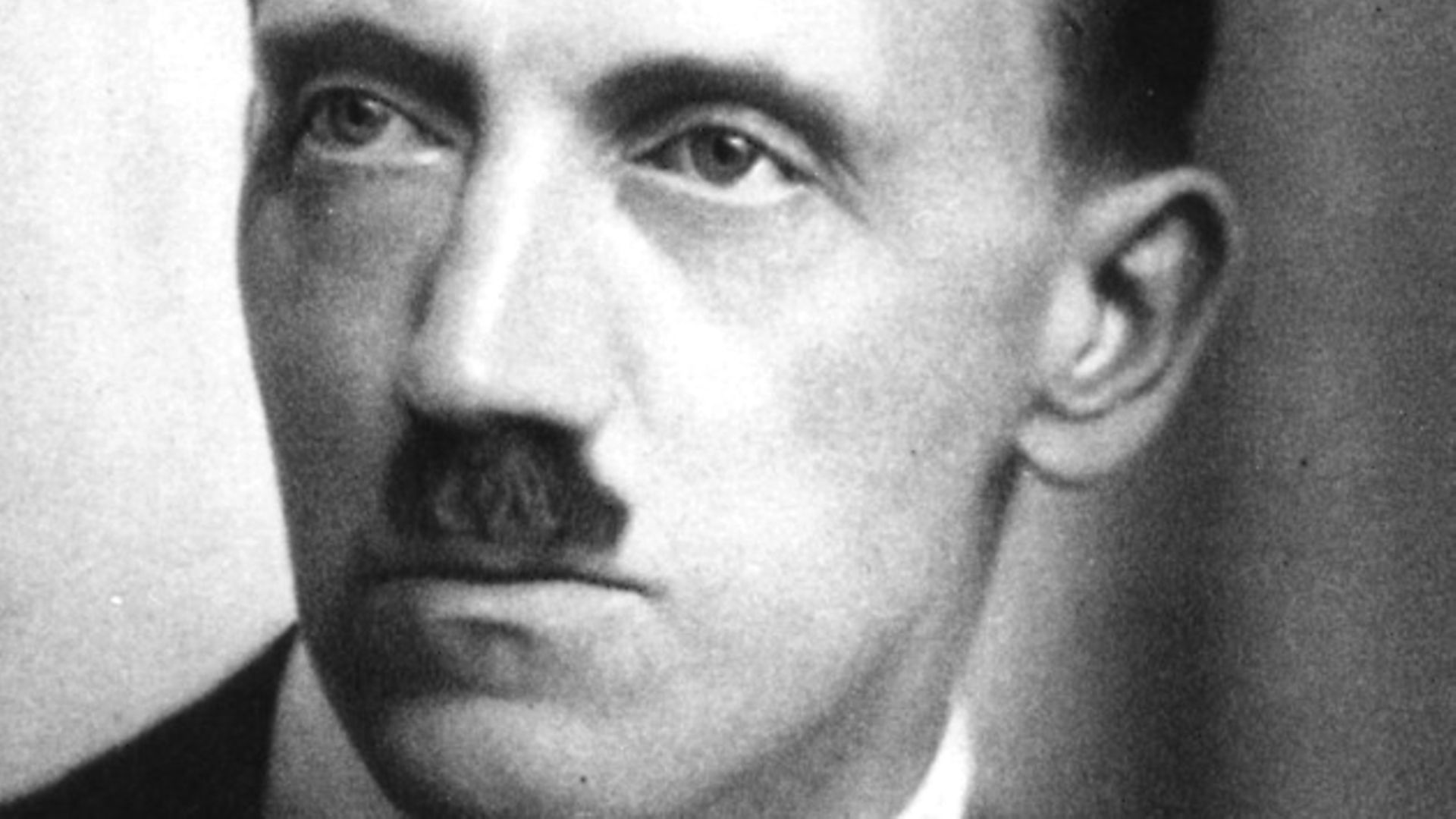

There is a thriving market for paintings by Adolf Hitler. But if the works are not valued for their artistic merit, just what is the attraction?

Ever owned a masterpiece of a renowned artist? A Picasso maybe? Or a Van Gogh? Well, if your funds don’t stretch that far how about a Hitler? There is an auction house in Bavaria that specializes in selling paintings made by Adolf Hitler. And they sell like hotcakes.

Plenty of people around the globe have indulged a somewhat sordid pleasure of owning a painting created by the biggest mass murderer in the history of human kind. Not that the Führer was a particularly good painter (come to think of it – he wasn’t a particularly good Führer either) but I guess that’s beside the point, since his paintings clearly achieve their value from something other than artistic accomplishment.

Artefacts relating to the Nazis have long exercised a lure for some. And given Hitler plugged away for some time trying to make it as an artist, there is a still plenty out there for those with this particular fascination. Between 1905 and 1920 he is said to have created between 2,000 and 3,000 paintings, drawings and water colours. Most have disappeared over the decades, but there are still enough circulating to draw in global audiences every couple of years.

The auction house Weidler in Nuremberg – a city with quite enough Nazi echoes, you might have thought – seems particularly skilled in tracking down lost Führer art. It has been selling works by the dictator since 2009, and securing some pretty eye-catching prices. One small watercolour painting titled Munich Register Office fetched 130,000 euros.

Last autumn, the auctioneers put up 24 water colours, one oil painting and two ink drawings by the Grofaz (a German acronym denoting ‘the greatest military commander of all time’, a derisive nickname given to Hitler) of which ten ended up going under the hammer.

There is no doubt about it – Hitler sells. Unsurprisingly, the buyers are rarely German (or Austrian) but, rather, international collectors. Hitler works have been purchased by buyers from Russia, China, France, Brazil, the United States or the United Arab Emirates. ‘These collectors do not specialise in this painter, but have a general interest in high-value art,’ said auctioneer Kathrin Weidler.

In 2015, a Chinese professor bought a water colour titled Neuschwanstein depicting the celebrated fairy-tale castle, built by mad Bavarian king Ludwig II, for 100,000 euros. When asked what sparked his interest in the work, the buyer simply stated that he wanted to study ‘Adolf’s painting spirit’.

A young Russian entrepreneur who bought three watercolours and an ink drawing for around 15,000 euros last year was equally tight-lipped regarding his motivation. ‘I buy out of historical interest’, he said.

This is the view of the auction house too, which has defended its sale of Hitler paintings because the works represent ‘historical documents’.

It has not completely cornered the market in Hitler art though. Four years ago, the Slovak auction house Darte sold a painting titled Nocturnal Sea, which depicts a full moon shining onto a glistening sea, for 32,000 euros. Jaroslav Krajnak, the auction house owner, claimed the picture belonged to a Slovak painter who might have known the dictator personally from his days as a penniless artist in Vienna.

Art featured prominently throughout Hitler’s life and, consequently, in the Reich he created. He had proclaimed his ‘artistic vision’ in his 1925 book Mein Kampf, and saw it as the duty of the Nazi leadership ‘to prevent a people from being driven into the arms of spiritual madness’ by ‘pathological excesses of insane and degenerate artists’.

‘Ugly art’, as he called it, belonged in a ‘suitable (mental) institution’. To support his misguided, twisted vision, in March 1933 Hitler announced in a government declaration that ‘blood and race will once more be the source of artistic intuition’. To ensure that the German people had a clear idea of what was deemed ‘degenerate’ art the entire cultural sector was controlled by the newly-created Reichs Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda headed by Joseph Goebbels.

Interestingly, Hitler kept his own paintings under lock and key, not – as we might assume – because they lacked artistic credibility, but to safeguard them for future generations. The Vienna art historian Birgit Schwarz claims that Hitler saw himself as some kind of genius, somebody who didn’t copy but was copied, and therefore his art had to be preserved as valuable inspiration for artists of tomorrow.

Unfortunately, as in so much else, Hitler was gravely mistaken. As Schwarz points out: ‘Hitler had no style of his own as a painter, but generally just copied.’

Indeed, the formulaic nature of his work is the reason it is so difficult to authenticate his paintings. Given the apparent interest in the works from collectors though, a cottage industry has grown up, over the years, to do just that. One of the foremost authorities for identifying Hitler’s paintings has been the Munich professor Dr August Priesack. A former Nazi official, who worked for the party’s central archive in the 1930s, he established himself as a Hitler expert after the war (and played a role in the authentification of the notorious ‘Hitler Diaries’ in the 1980s). In collaboration with the American collector, Billy F Price, Priesack attempted to put together a catalogue of Hitler’s artwork – although cultural historian Frederic Spotts has estimated that two-thirds of its contents are forgeries. In attracting this form of imitation – and only in this – can Hitler be said to have achieved the same status as some great artists.

As for divining any sort of message in his work, you will seek in vain for any hint of the mayhem and destruction he wrought in his life. What you find are castles, flowers, buildings, nudes and landscapes. Peaceful, bland, traditional – an escapist simplification of life.

Since Hitler copied what he deemed correct, art critiques have argued that you can’t learn much from his works about the man himself, because they are so lacking in personality.

But this doesn’t seem quite true, since not having a recognisable personal style is, in some ways, also a form of personal style. In the absence of what we might call self-expression or critical reflection, Hitler’s paintings show his true colours and reveal at least some of the ideological foundations of National Socialism and how it was intended make this world a better place: remove all complexity and contradiction, erase all traces of individuality and creativity, and replace it with uniformity.

Since the Nazi dictator saw himself as the god-king genius, following in the footsteps of Prussian king Frederick the Great, that ultimate enlightenment monarch, he merely expected his followers to copy him and follow orders, to ultimately construct his own personal Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk (literally ‘total work of work’): the Third Reich.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37