As the Cold War proxy conflicts from Cuba to Vietnam raged, and nuclear and chemical weapons proliferated to the point where Soviet or American leadership could annihilate life on earth many times over with a single command, a supermarket opened in Zagreb and helped change the course of history.

The supermarket was American and it was a fake; a 10,000 square foot recreation located at the United States pavilion in the 1957 Zagreb International Trade Fair, and stocked with aisle upon aisle of genuine fresh, frozen and canned produce flown in from the States.

A report in the New York Times from September 8 of that year gives a sense of its impact on the ordinary people of Yugoslavia, living under the country’s single-party socialism:

A typical American supermarket, the first ever shown in a Communist country, was the rage of Zagreb today. Yugoslav housewives jammed the new US pavilion to see for themselves how American women do their shopping in a veletrznica (supermarket in Serbo-Croat). “Look at the meat,” said one goggle-eyed visitor. “It’s all packed and assorted, the price is marked on it and you just know it’s clean.” “Say what you like but we don’t have such grapes in Yugoslavia,” a second woman remarked to her husband. “Here we get those green sour grapes.”

Next door, at the USSR pavilion, Soviets officials were offering free helicopter rides to news reporters in a desperate bid to draw attention from the allure of ripe bananas, lamb chops and a multitude of gaudy breakfast cereal boxes.

It wasn’t just Yugoslav housewives who were goggle-eyed. Their president, Marshal Josip Tito, bought the exhibition, including its self-service checkouts, and used it as part of his strategy to blend elements of US-style capitalism with communism in what became known as Coca-Cola Socialism.

A month later, the Soviets would launch Sputnik 1 into earth orbit and create panic among American politicians that they were dangerously behind in the space war stakes. But when it came to putting food on the table, conveniently and cheaply, the Americans had the farm wars in the bag. And their Zagreb supermarket would prove much more influential in ending the Cold War than either nuclear missiles or satellites.

The very concept of a supermarket was, of course, much more than a better way of doing the weekly shop. A supermarket cannot exist without an entire system of intense agriculture and efficient distributeion lines all converging to fill those shelves.

It was very much an American invention (the first supermarket in the world was opened in New York’s Queens borough in 1930 – The King Kullen supermarket, invention of former grocery clerk Michael Cullen). By the late 50s, what the women (and surely, even if unacknowledged by the New York Times, men) of Zagreb saw was a clear signal of capitalist superiority in something that mattered much more to them than the conquering of space or new ways to facilitate human extinction: Cheap and plentiful food.

The use of this supermarket as a tool of propaganda was hammered home by a message from president Dwight Eisenhower at the pavilion entrance. It read: “All countries today stand on the threshold of a more widely shared prosperity, if they utilise wisely the knowledge and science available to this age. International fairs help to spread this knowledge and to quicken man’s imagination and ingenuity in the creation of a better life for all.”

In other words; Look at what we’ve got with capitalism. Look at what they’ve got with communism. Or even more bluntly: American bellies are fuller than Soviets’.

There was another aspect to the supermarket that would have been shocking to Yugoslav visitors – the concept of self-service. Before the supermarket, shopping was delivered to your basket via the intermediary of a shopping clerk. You queued up, asked a clerk for something, and if it was available it was handed to you.

Now, suddenly, you walked right in and picked whatever you wanted right off the shelves. More than mere convenience, this was permission to choose, permission to reject, permission to change your mind. It was a delicious new form of freedom.

Like wheels on a suitcase, it was a bleeding obvious idea that had taken mankind centuries to invent. But in the case of the supermarket, its invention was the logical conclusion of an intense focus by the US government; a deliberate strategy to drive down food prices by concentrating attention on both its production and distribution.

The US Department of Agriculture, established in 1862, invested heavily in technologies and science to make food more plentiful and cheaper; including hybridising seeds, researching animal husbandry, developing new farm machines (such as the automated tomato harvester) and fertilisers. It had a particular fascination with how food could better be moved around the nation, even researching better road surfaces and road-building.

Photo: Corbis via Getty Images.

There was a “Chicken of Tomorrow” project (the video is there on YouTube), a three-year programme to improve chicken and egg production. In 1910, the average American ate 10lbs of chicken per person per year. It was as expensive as lobster and the least popular protein on the table, well behind beef, pork and fish. A century later, Americans eat around 70lbs of chicken a year and it’s the world’s number one meat. The Chicken of Tomorrow project might sound like an Armando Iannucci invention, but it’s effect today is visible on every dinner plate and every high street in the world.

Yugoslavia was not the first developing nation to succumb to the allure of American supermarkets, and the capitalism that underpinned them. At the end of the Second World War, Nelson A Rockefeller created the International Basic Economy Corporation.

Its mission was to introduce American ideas on farming and retail to stimulate the economies of Latin American nations, twisting them away from traditional small localised markets towards national economies increasingly benefitting from (and dependent on) American market know-how, produce and capital.

These countries would then be happy allies, not malcontent backwaters where political unrest could easily take hold and revolution spread.

Rockefeller, later to serve as vice president of the US and governor of New York, used the latest Department of Agriculture research to develop model farms in Brazil, Ecuador and Venezuela.

In Venezuela, he opened a string of supermarkets, designed to introduce the concept of greater production and consumption, albeit at lower profit margins, bringing down food prices and placating fast-growing impoverished urban populations.

Keeping bellies full was not just good business, Rockefeller believed, but a global geopolitical strategy to deliver lasting peace through what Franklin Roosevelt had previously described as “freedom from want”. For his part, Rockefeller called this blending of business, philanthropy and politics “enlightened capitalism”.

Two years after the Zagreb supermarket, the American’s rubbed Soviet noses in the benefits of enlightened capitalism once more, this time on their home turf at the American National Exhibition in Moscow.

This six-week showcase of the best of American technology and art – part of a cultural exchange between the USSR and USA – featured not just canvasses by Jackson Pollock and cars by Cadillac, but a split-level American house, bursting with food and hi-tech labour-saving machinery like washing machines and refrigerators. It was supposed to represent the home of an

average American, costing $14,000. Once more: Get a good look at what capitalism does for you, folks!

At the grand opening, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and US vice president Richard Nixon bantered together in front of reporters and cameramen in the dummy ranch house, in what later became known as the Kitchen Debate.

With the benefit of hindsight, this unscripted exchange in the surrounds of a dummy American ranch is one of the most significant, and telling, conversations in post-war history.

Khrushchev, looking every bit the delighted owner of the Kentucky Derby winner in white homburg and light suit, mocked the proliferation of time-saving devices, including a machine that squeezed the juice from a lemon.

Anyone can squeeze a lemon by hand, he told a surprised Nixon, and asked if this was standard kit in an American kitchen. It was not, Nixon replied, just a prototype. One-nil to Nikita.

Well, at least it’s a technology to improve lives, not kill people, Nixon shot back. 1-1.

Khrushchev returned: This is all you’ve got after 150 years on independence, a lemon squeezer? Don’t you have anything to put food into people’s mouths and then push it down? The USSR has only been in existence for 42 years; we’ll soon catch up and then go past you… Bye, bye! Khrushchev 2, Nixon 1.

Happy with his victory, Khrushchev suggested the Kitchen Debate should be translated and broadcast simultaneously to citizens of both nations. Nixon happily agreed and the resulting publicity the vice-president got helped springboard him deeper into the national consciousness and, later, the White House.

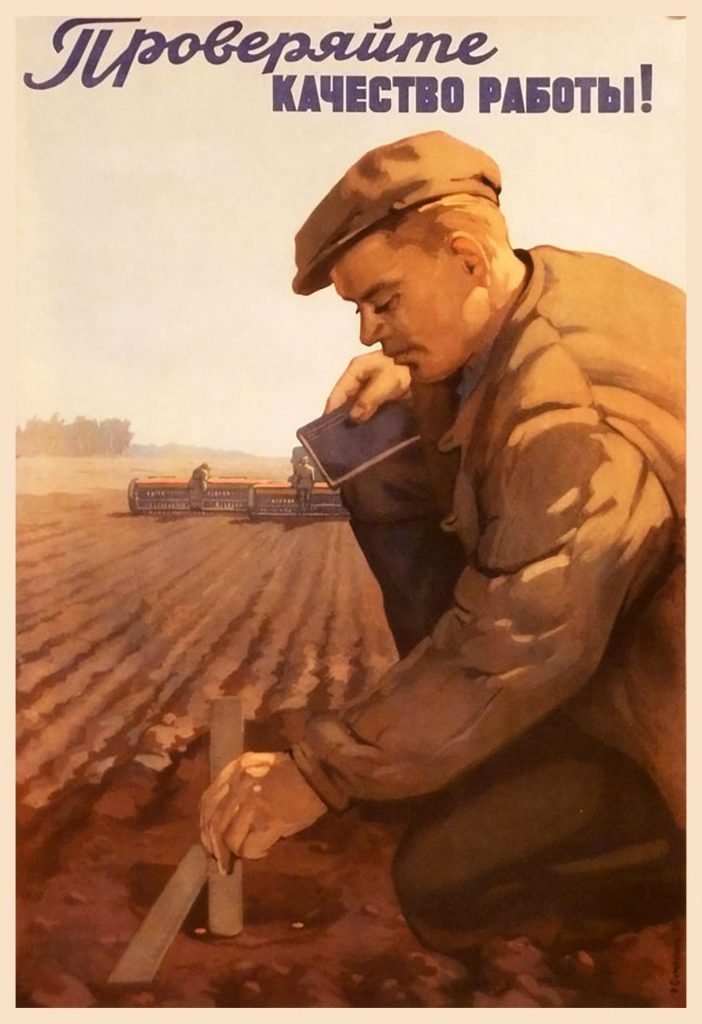

Photo: Ruben Suryaninov/Digital Soviet Art/Getty Images.

Khrushchev’s braggadocio, however, was all bluff. Four years earlier, a worried politburo had sent a group of Soviet agricultural scientists to the States to study why their grain production fell so short of America’s.

What they saw – the benefits of a decentralised and capital-driven quest for cheaper food at lower margins – was simply unrepeatable within the Soviet Union’s rigidly dictatorial, and highly inefficient, collectivism.

Within years, Khrushchev was striking bargains for the import of grain from his greatest rival to put bread on the table for Russians, a humiliation many believe was a factor in Khrushchev’s ousting in 1964.

Nixon in. Nikita out. How history turns on a mechanical lemon juicer.

American supermarkets were not just a shiny new way to buy food. They represented in a very concrete manner, the swift economic progress and prosperity capitalism could deliver over communism. When ordinary people saw them, they knew they were looking at the future.

What they may not have understood – nor perhaps fully appreciate even today – was that their existence was only possible because of the differences in approach of the two major economic philosophies of the 20th century.

They led to the fall of one system and the global dominance of the other, for better or worse. In the hands of the Americans, supermarkets weren’t shops.

They were weapons of counter-revolution. As Nelson Rockefeller put it: “It’s hard to be a communist with a full belly.”

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37