High up on the small island of Santa Clara, a disused lighthouse looks out over the rocky bay of Donostia-San Sebastián, on Spain’s Basque coast. All around, cliffs rise up in jagged shards that seem to defy their ancient geology to reach skywards, as if they are somehow still breaking through the earth’s crust, the crashing sea keeping time as it has done for millennia.

Against this elemental panorama, the 19th century lighthouse provides the setting for Hondalea, the Basque word for the ‘marine abyss’ created by Spanish artist Cristina Iglesias for her native city of Donostia-San Sebastián. Hondalea was unveiled earlier this summer and features in a new book Liquid Sculpture: The Public Art of Cristina Iglesias, edited by Iwona Blazwick and Richard Noble.

Inside the lighthouse, a long drop reveals a rocklike formation, cast in bronze and washed by a perpetual tide, as if the lighthouse is a portal to the earth’s core.

“Of course it’s a fiction, it’s a total fiction – it doesn’t exist!”, says Iglesias, over a shaky Zoom connection still good enough to mark the contrast between her sunfilled room in Spain and mine, still lamplit in gloomy London. “But you believe it is true. You are confronted by an abyss and right at the bottom is a cave or grotto made of bronze. From time to time a tempest appears, as if waves are coming in from the sea – which of course is much further down, but you believe it’s the real sea. It’s as if these bronze caves lead to others, and that maybe the whole island is filled with caves of bronze, all connected to the sea.”

The project is a feat of engineering as much as imagination: disused since the 1960s, the lighthouse has been hollowed out and its foundations excavated to a depth of nine metres, a hidden mechanism to control the movement of water installed beneath the bed of cast bronze forms.

The sculpture was first mooted in 2016, when Donostia-San Sebastián was Cultural Capital of Europe. The occasion prompted the mayor to ask Iglesias, who grew up in the city, to consider how she might contribute to its collection of notable public sculptures which include Peine del Viento (Comb of the Wind), 1977, by Eduardo Chillida, and Jorge Oteiza’s Construcción Vacia (Empty Construction), 2002, works that with their abstract forms and dialogue with the sea, draw obvious parallels with Hondalea.

For locals, the island of Santa Clara has a particular significance. It is both remote and familiar, and though it can easily be seen from the city it is often inaccessible due to poor weather. It was the site of a hermitage in the 14th century, and in the late 16th century, it was used to quarantine plague victims.

Recalling childhood visits to Santa Clara, Iglesias explains the island’s relationship to the city, and its appeal as a location, in an interview in Liquid Sculptures: “The island had a mysterious presence. Sometimes we’d go there in a little boat, but only to the shore, and we wouldn’t really go further.

“There was a feeling of adventure in going there, a sense of escape. Even though it’s an island, it’s really part of the city: you see it from the beach and the promenade just above it.”

Hondalea’s bronze caves might belong in a Grimm’s fairy tale, but their forms are closely modelled on the spectacular geology of this stretch of the Basque coast, where the Pyrenees meet the Bay of Biscay. Sedimentary rocks formed into corrugated vertical layers called flysch are the dramatic results of the tectonic events that created this mountainous region around 60 million years ago: “If you look back to the land from the sea, it’s like looking at the history of the earth”, says Iglesias.

Luis Lopez Zubiria

Since 2015, a 13km stretch of cliffs to the west of Donostia-San Sebastián has been designated a UNESCO Global Geopark.

Wind, sun and salt have created an array of textures and patterns in the rock that Iglesias compares to Moorish ‘jalousies’, decorated shutters that traditionally allowed those inside – especially women – to look out without being seen.

Iglesias took impressions from these rocks, which were then cast in bronze before being assembled at the bottom of the lighthouse.

Time and memory are essential elements of Iglesias’s work, galvanised here by the sounds of the sea which offer a continuous accompaniment to Hondalea.

The echoing space of the lighthouse amplifies the wave sounds artificially generated by a system of hydraulics, imitating nature, but very deliberately composed. “What you see is affected by how it sounds, and that stays in your memory”, says Iglesias.

Memory and history do not necessarily imply permanence, and for Iglesias, the poignancy of the piece derives from the vulnerability of this precious, irreplaceable landscape, whose fossil-rich geology was key to developing the theory that dinosaurs were wiped out by an asteroid.

Further inland, a honeycomb of caves preserves traces of early human activity, the Ekain cave containing naturalistic paintings of animals made 10-14,500 years ago.

Climate change presents an immediate and significant threat, with rising sea levels directly affecting the rate of erosion. Raising public awareness is important to Cristina Iglesias, and by providing an intense, imaginative and meditative experience, she believes that art can be a force for social and political change.

“It’s important in the times we live in, that art can get close to the experience of nature, and to the protection of nature, and to discussions about this”, she says.

■ Liquid Sculpture: The Public Art of Cristina Iglesias, edited by Iwona Blazwick and Richard Noble, is published by Hatje Cantz

Water Works

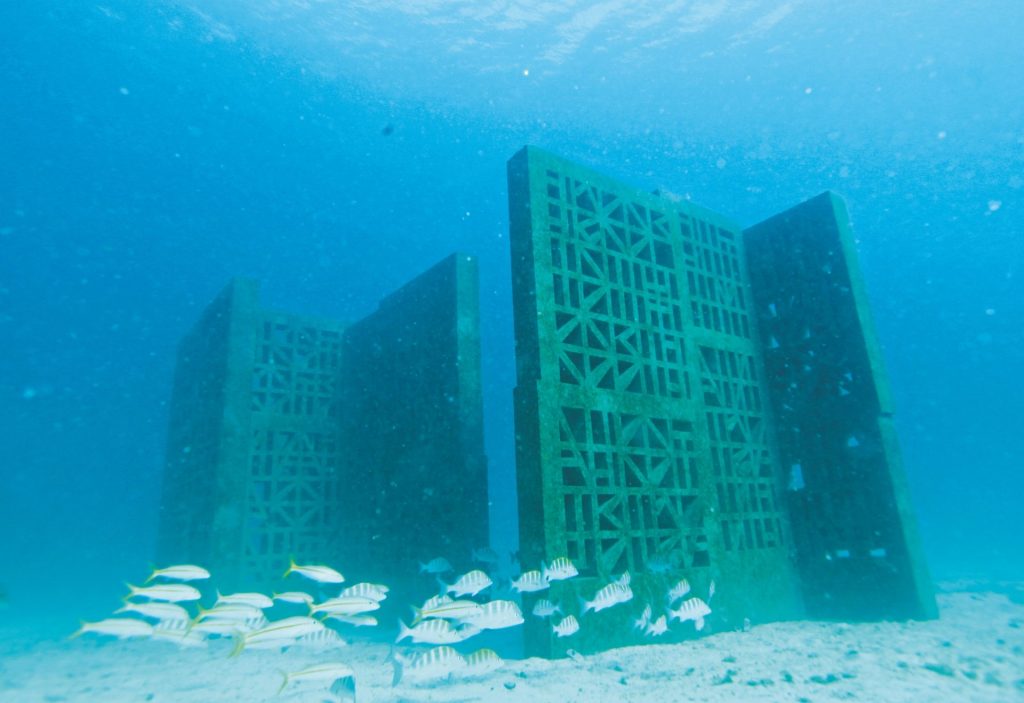

Another work by Iglesias featured in Liquid Sculpture is Estancias Sumergidas (Submerged Chambers), 2010, which was installed on the ocean floor in the Sea of Cortez in Baja California Sur, Mexico, and forms a habitat for sea life, from corals, to starfish and manta rays. Visible from the water’s surface, it features a series of latticed screens which create underwater spaces that will be transformed over time as new life is generated.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37