When Theresa May told the Conservative Party conference ten years ago that an “illegal immigrant” could not be deported because he had a cat, this was not entirely true. Somebody had a cat somewhere, but it certainly wasn’t preventing a deportation under the right to a family life.

“Catgate” has entered legal and political folklore, but it isn’t really funny.

Even though discredited, it has become part of a list of faux grievances pedalled by a long line of politicians playing up the burden of human rights laws and persuading the public that they should be watered down. Similar tactics played up EU regulations before Brexit.

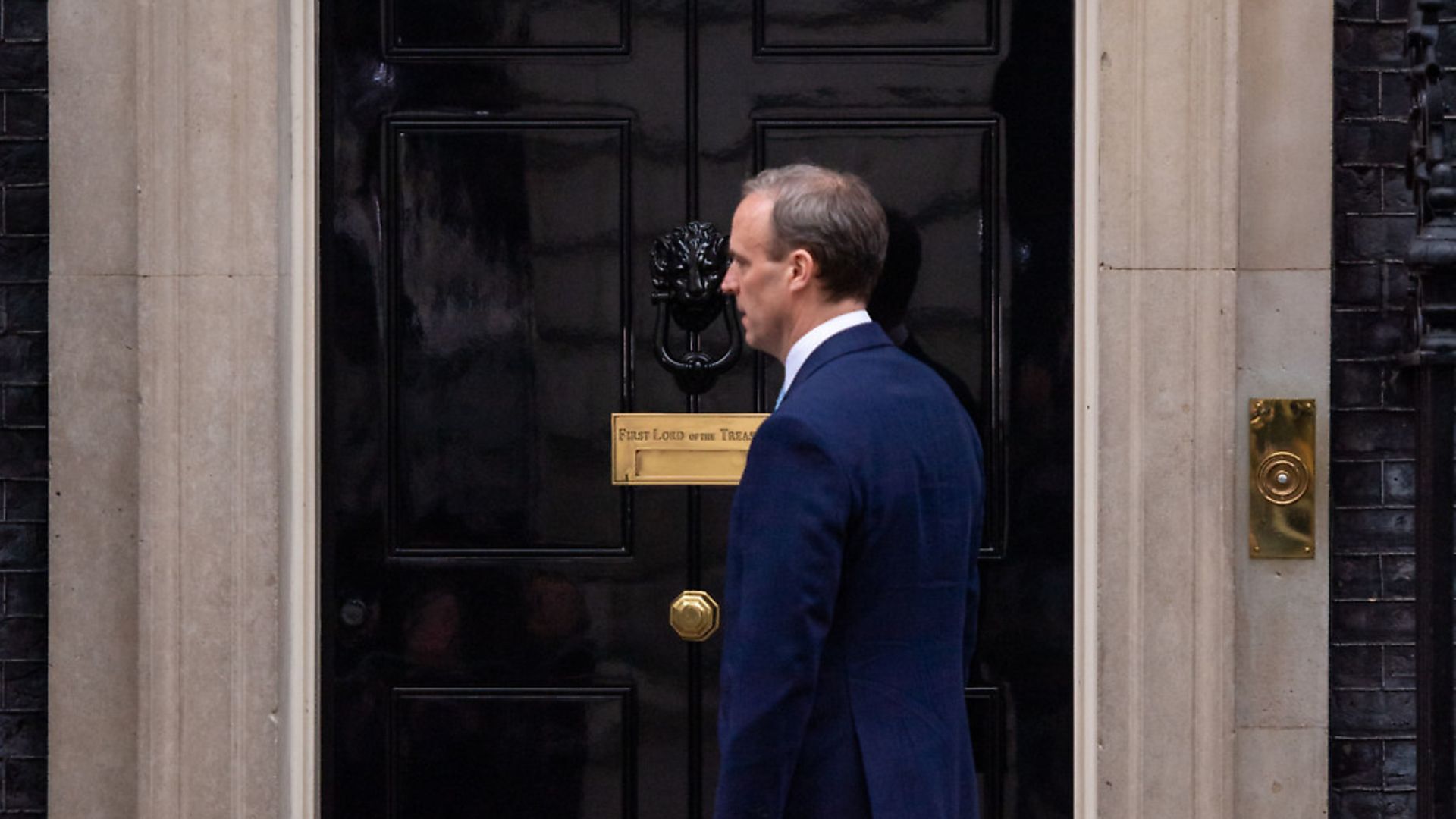

Last weekend the two issues linked up, when justice secretary Dominic Raab said he was working on a “mechanism” to allow the government to “correct” court judgements that ministers believed to be “incorrect”.

He was particularly vexed by the influence of the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, and the prospect of European judges meddling on matters such as British soldiers fighting abroad. The ECHR is tied to the European Convention on Human Rights, to which the UK is a signatory. It is emphatically not the EU’s European Court of Justice. However, it elicited cheers from the usual suspects immediately triggered by the words “European” and “meddling”.

Lawyers and rights groups were aghast. “Why is there a need to “devise a mechanism” for government to introduce legislation? We already have these things called “Acts of Parliament”, tweeted Jonathan Jones, who quit his role as top legal civil servant last year over government plans to break the law. “Unless of course there’s another attempt to reduce Parliament’s involvement.”

Some believe Raab was playing to the gallery. But whatever happens now, another blow has been struck in the deep-rooted war on rights, which has become a surefire way for politicians to play tough and woo voters.

When former Home Secretary Sajid Javid made the controversial decision to refuse ISIS bride Shamima Begum’s request to return to the UK to stand trial, stripping her British citizenship, he proved both that someone’s human rights could after all be legally trumped by security concerns, and that you could be feted for standing strong against a troubled teenager.

Which begs the question – why is it that so many people seem to hate human rights?

“There’s clearly a perception that public attitudes towards human rights are negative,” Benjamin Ward, deputy director, Europe and Central Asia, at Human Rights Watch, told me. “It’s a combination of things — it’s been given a bad name, it’s associated with the rights of others as opposed to ours, it’s been scapegoated and associated with Europe.”

Hardly anyone ever thinks human rights laws are for or about them. They tend to be invoked to protect minorities, and minorities – such as Roma, travellers, prisoners, refugees, migrant workers or foreign extremists – are not generally popular, especially among poorer voters who feel they are in competition for resources.

Then there’s the tabloid treatment, which publicly highlights cases invariably linked to “bad foreigners” that the government wants to deport – criminals, terrorists, alleged benefit cheats – turning off potential sympathy. Reporters and politicians hone in on any absurdity offered by desperate defence lawyers – never mind that these arguments are dismissed, the image sticks and everyone’s appalled.

So the wider applications of the HRA get lost, laments Gracie Bradley, director of the campaign group Liberty. “That means what we want to talk about is not in the news – the Hilllsborough families using the act to get justice; LGBT veterans invoking it to get their medals back, families using it to see their loved ones in care homes during lockdown,” she told me.

As for governments, it’s usually obvious why they aren’t keen on human rights legislation. The laws restrict their power and room to manoeuvre, they allow ordinary people to hold them accountable. And it’s embarrassing when they’re publicly thwarted, especially if it involves a telling off from foreigners.

This isn’t just a Conservative problem. The HRA became law in 1998 under Labour, but home secretaries Jack Straw and David Blunkett didn’t shy from painting it as an impediment to doing their job properly when they stumbled, particularly over deportations. Labour were far from making a convincing public case for the law they championed.

One big flashpoint, which straddled both governments, was over a 2005 ECHR ruling against the UK’s blanket ban on prisoner voting rights, a limited judgement presented explosively to an outraged public. The debate rumbled on until the referendum, and was a useful backdrop to May’s “hostile environment” at the Home Office.

This battle is not entirely new. Since emerging as a concept, human rights have been weaponised and rebuffed throughout history. They were used as a justification for the nation state – which was supposed to promote them. As it became clear in the 19th century that the Enlightenment vision for human rights left out the working masses, the growing liberal and socialist fight for them set the stage for nationalism and cultural rights.

The debate over whether rights are universal goes back to ancient times – 2,000 years ago, Herodotus argued there were no universal ethics. The tension between rights and security predates the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and survived well beyond it.

But at the turn of the century, in the West, at least, human rights were publicly a considered uncontroversially desirable.

Now, with the recent rise of populism, leaders with big votes, from Viktor Orban to Tayyip Erdogan, see their mandate as legitimizing everything they want to do in the name of the “will of the people”. In that spirit, they attack pesky human rights legislation with a nod and a wink to their cheering voter base: “You don’t like this either, do you?”

In 2014, law professor Eric Posner, in his book “Twilight of Human Rights Law”, argued that human rights legislation had become useless. Compliance was atrocious, with international institutions unequipped and many states completely uninterested in enforcing them, he said.

His keen readers include the current Conservative attorney general, Suella Braverman. She drew on Posner’s work to argue, on international Human Rights Day in 2015, that Britain’s “obsession” with human rights overshadowed traditional values such as generosity and responsibility.

Braverman set her concerns into her keynote speech to the Public Law Project Conference this week, highlighting judgements including the Supreme Court finding that parliament broke the law when proroguing parliament. Her worries about parliamentary sovereignty tied in with Raab’s interview.

Anger from the time tabloids attacked the judges as enemies of the people may have subsided, but the effect is being felt. I’m told privately that some lawyers worry about which cases to accept, and there’s a sense the Supreme Court, without the progressive Baroness Hale and some of her colleagues, is making more conservative decisions.

“I do think the judiciary has been damaged in all this,” Cambridge law professor Catherine Barnard told me.

Yet human rights and an independent judiciary aren’t necessarily right-left issues. The Bright Blue conservative think tank published a report back in 2017 saying the Tories should not repeal the HRA nor withdraw from the ECHR. It said the first proponent of the Bill of Rights, a precursor to the current act, was the future Tory lord chancellor Quintin Hogg, and criticised the post-May scepticism as “philosophically flawed and politically unwise.”

The international implications of Britain’s rebellion are dangerous. Barely a day goes by in which the illiberal press and politicians in places like Russia, China, Poland or Turkey don’t produce shrieking Op-Eds or speeches latching on to perceived “hypocrisy” by Western governments preaching reform in authoritarian states.

Even the debate about whether human rights are a nuisance can be used to justify the horrific unpicking of hard-earned human rights legislation, including women’s abortion rights currently under fire in Poland and Texas.

It’s no coincidence that both Russia and Turkey are threatening to walk away, Ward said. “In all these cases it’s fundamentally about objecting to being subject to the European Court of Human Rights and all it stands for.”

If the UK did pull out, it could cause yet another Brexit headache, since current trade and cooperation arrangements and the Northern Ireland protocol partly hinge on accepting the court’s jurisdiction.

Even just watering down the HRA has repercussions. If legal avenues here are reduced, more complainants would take their case to Strasbourg, a court of last resort. An own goal if ever there was one.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37