He is everywhere. In the newspapers, on TV, in bookshops and meeting halls. And last week even on the front page of gossip magazines Paris Match and Voici, photographed in the sea, entwined with his young assistant and, it now seems from the reports, mistress. Officially, he is promoting his latest book La France n’a pas dit son dernier mot (‘France hasn’t said its last word’).

Yet the reality is that Eric Zemmour is testing the waters in anticipation of his likely candidacy in April’s presidential election. “I am not standing, and if I stand, I will choose my moment,” he says regularly. The fact is, no one doubts for a minute that he will – if he can. A presidential campaign requires significant financial backing and the support of at least 500 mayors across France (out of 42,000). Right now, he has neither.

In the meantime, he is raising his profile. Zemmour is not unknown in France. In fact, over the years, he has become a feature of several political TV programmes where he has pronounced increasingly radical and controversial views.

More recently, he has been transforming himself from professional media provocative into a populist. Politically, he stands at the far-right, actually at the extreme far-right. His views are seen as even more radical than those of Marine Le Pen, leader of the Rassemblement National (RN), formerly known as Front National.

He is an advocate of the controversial white supremacist theory of the ‘Great Replacement’ and the ‘Clash of Civilisations’. Unsurprisingly, he is obsessed with Islam and immigration, but he goes further.

In his latest book, he strongly defends Maurice Papon. He did the same with Marechal Pétain in one of his earlier books. He also compared the Islamist murderer Mohammed Morah, a French-Algerian, with his Jewish victims, a French teacher and his two children killed in cold blood at a school in Toulouse in 2012. Because the first was buried in Algeria and the latter in Israel, none of them, according to Zemmour, “really belonged to France”.

Six months before the presidential election, the 63-year-old Zemmour has become a bit of a problem for the far-right and for the conservatives. The polls currently suggest that Le Pen will be the candidate to get through to the second round run-off against Emmanuel Macron.

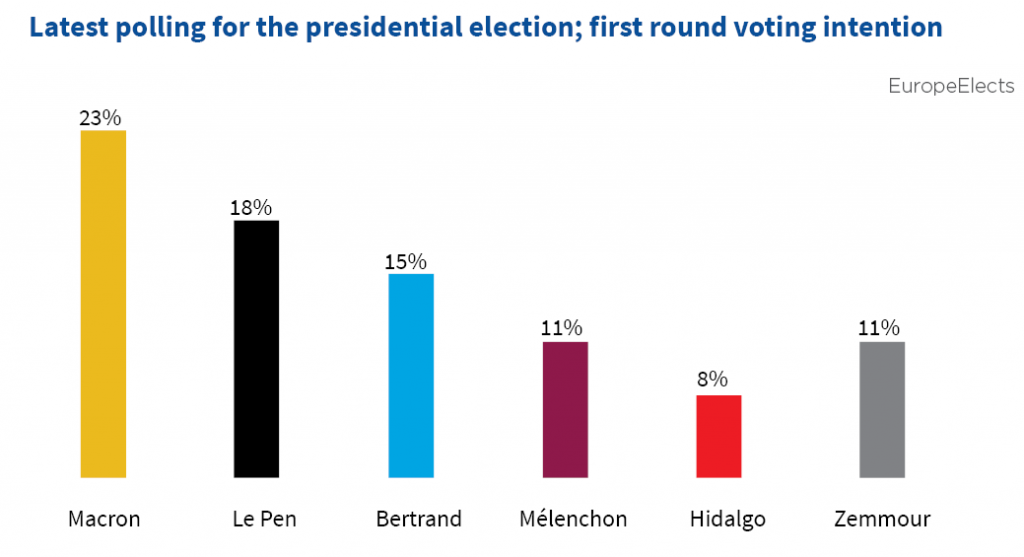

But a recent poll indicated that Zemmour could attract around 11% of the votes in the first round. That is only two points less than Xavier Bertrand, the most prominent candidate for the more centrist conservatives.

Also, Zemmour could split the vote for the far right, reducing Le Pen’s support, which currently stands at about 18% in the first round. All this could play into the hands of the left, where Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s support runs at similar levels in the polls.

Born in Montreuil, on the outskirts of Paris, Zemmour is the son of a Jewish family from Algeria who arrived in France in the 1960s, after the war for independence.

His dad was an ambulance driver and his mother stayed at home to raise her two sons. He studied at Sciences Po, but failed twice when trying to study at ENA (Ecole Nationale d’Administration), the post-graduate institution which has provided the majority of the elite in France.

Presidents Valery Giscard d’Estaing, Jacques Chirac, François Hollande and Emmanuel Macron all studied at l’ENA, as did current prime minister Jean Castex and his predecessor Edouard Philippe. Zemmour’s 28-year-old assistant Sarah Knafo – whom he was photographed embracing – also studied there.

Zemmour began his career as a journalist in 1986 at Le Quotidien de Paris, a conservative newspaper. He stayed ten years before moving to Le Figaro, the most prominent conservative title. For a long time, he was a classic political writer, with a nice style, very conservative views, occasionally provocative, but not outrageous.

Since his first appearance on TV in 2012, in a political programme on iTélé, his views have become more and more extreme.

He is a good writer and has published several books, among them the best-seller Le suicide français, which sold 400,000 copies.

He has become widely known since joining Cnews in 2019 for a daily talk show. At Cnews, which resembles Fox News in the US and is owned by the wealthy industrialist Vincent Bolloré, Zemmour has been able to develop his anti-islam, anti-women, anti-gay rhetoric. He is even anti-bikes, having claimed in a newspaper editorial that “the bicycle is the enemy of humanity”.

He has also said he would prohibit families from giving children non-French first names and introduce outright bans on the wearing of religious symbols, such as Islamic headscarves, because they stand in the way of immigrants becoming true French citizens.

Occasionally, during his more recent career as a polemicist, he has been sacked after one too many outrageous comment, but he has always found somewhere else to express his hatred.

He has been found guilty twice of incitement to hatred and racism, but that has not prevented him from finding other media outlets who welcomed him and his ability to attract attention.

Some have suggested he could be a new Macron, a relatively unknown candidate who becomes the unexpected winner. Like Macron before 2017, Zemmour has never been a candidate in an election. But the similarities stop there. Macron was a high ranking minister in Hollande’s government before running for president. Zemmour on the other hand has no government experience at any level.

Others compare him to Trump, a creature nurtured by media and specifically TV, a populist, initially laughed at and ridiculed but who managed to attract millions with his anti-elite and populist views.

Undoubtedly, Zemmour has been nurtured by TV. But he is perceived as an intellectual whose views have, over the years, become more and more extreme.

Most of all, Zemmour’s discourse revolves around two focal points only: Islam and immigration. On all other subjects which might be raised during the presidential campaign – social issues and the environment, for instance – he has not much to say. At least not yet. That was very apparent during a debate organised last week by BFM TV between him and the leader of La France Insoumise, the far-left Mélenchon.

A little more than six months before the first round of the election, Zemmour is omnipresent in the French media. But the moderate right has yet to decide which candidate will stand, and they have at least three serious contenders, Xavier Bertrand, Valérie Pécresse and Michel Barnier. On the left, the Socialists remain divided, even if Paris mayor, Anne Hidalgo, who has officially declared her intention to run, has a good chance of becoming the official candidate. As for Macron, he hasn’t said anything yet. He is the president and might declare his candidacy much later in the campaign.

Time will tell when it comes to Zemmour. However, before any candidacy he will first have to focus on attracting not just attention, but the signatures of those 500 mayors and the financial backing.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37