When the River Turia burst its banks on October 14, 1957, Spain’s third-largest city was badly flooded, water rising to first-floor windows in some neighbourhoods and more than 80 people dying.

It was dubbed the Gran Riada de Valencia (“Great Flood of Valencia”) and city officials decided, finally, to take action – the river had burst its banks many times previously over the centuries, although to a lesser degree.

A plan was drawn to divert the river via a man-made channel to the south, bypassing the city, and this project was completed in 1973. Thus the safety of those living close by was secured. But something else happened too: Valencia gained roughly six miles of land, around 200 metres wide, snaking through its centre.

This is a lot of extra territory for an ancient city to find unexpectedly in its possession and a forward-thinking local planning department, refusing to give in to lobbying to build a big new road, housing and office blocks, designated the space as parkland. This was duly named Jardin del Turia.

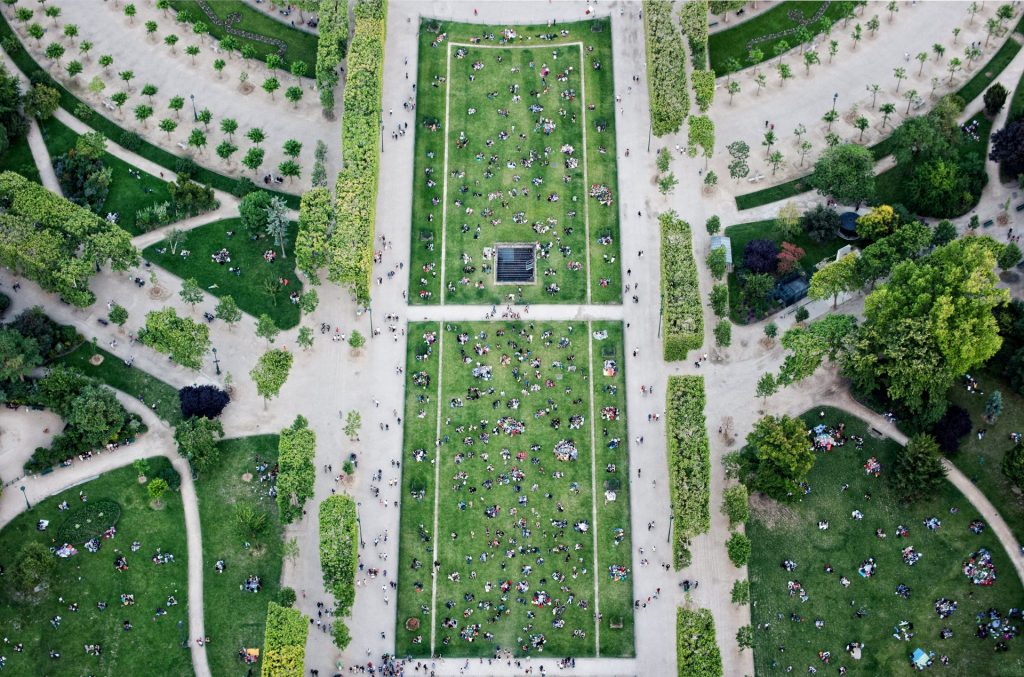

It proved a resounding success. On the one hand, the quality of life of Valencians improved immeasurably with a wonderful space planted with orange and lemon trees, flowerbeds, emerald lawns and shaded woodland, alongside tennis courts, athletics tracks, a wildlife reserve and, at the Mediterranean Sea end, a marvellous, futuristic City of Arts and Sciences centre. On the other, it has also offered a tantalising glimpse of how cities everywhere could be better managed – park-wise – in the future.

If the pandemic lockdowns have taught us anything it is to love our local parks. They have also provided an opportunity to take a fresh look at the role urban greenery plays in our cities (as those enlightened planners did so long ago back in Valencia).

Confined periodically as we have been to our houses, with horizons shrunk to what is ‘local’, parks have suddenly come to the fore, especially in large cities such as London where one in five people do not have access to their own garden or balcony. This figure across Britain is one in eight.

We have taken evening perambulations after long hours cooped up working from home. We have met friends and family for strolls. We have enjoyed picnics on greens. We have even, as restrictions lifted, held parties in the park (some people sadly failing to clear the mess afterwards).

In a time of need, city parks have provided crucial, much-loved places to escape the confines of our front rooms. Green spaces that might previously have been stamping grounds mainly of dog walkers, joggers, the odd down-and-out and those pushing prams have taken on an importance to almost all of us. After all, where else did we have to go?

Little wonder, then, the fierce reaction of locals to park closures by some overzealous city councils, from Middlesbrough to London, in the early days of the pandemic.

Take what happened in London’s Tower Hamlets. After Victoria Park was shut to prevent “disorderly behaviour”, a Parks Action Group was swiftly formed, the mayor of Hackney attacked for letting authorities “overstep their legal powers”, and the park hastily reopened – apologies all round.

Victoria Park, protestors pointed out, had been established in 1845 to allow the working classes the chance to enjoy a clean green space during industrialisation, as so many city parks were in Britain and elsewhere around the globe in the 19th century.

Most, like Victoria Park, were the handiwork of benevolent local politicians who called upon the concept of “rational recreation” to back their schemes, often commandeering parts of common land or partially forgotten territory on the edge of cities before suburbs existed as they do now (the land at Victoria Park was said to have been a hideout for some avoiding transportation to Australia and had even been nicknamed “Botany Bay”).

In the UK, a parliamentary committee at the time had recommended the opening up of green spaces for the “middle or humbler classes” and with the Town Improvement Clauses Act of 1847 and the Public Health Act of 1848 that were to follow, authorities from Derby to Leeds and London had the means at their disposal to act.

Such historical ghosts seemed to swirl in the air during those early lockdown showdowns. Modern-day busybody councillors had no right to encroach on these seemingly sacred spaces. “VICTORY FOR VICKY” screamed the headlines in the local press.

Of course, it has not just been in Britain that urban parks had their moment in the limelight during Covid. The majority of people across the planet are now city dwellers. According to the United Nations, 55% of the world’s population lives in cities. By 2050, this is expected to rise to 68%.

Given that the world’s population has ballooned from 1.6 billion in 1900 to 7.8 billion now, this represents an awful lot of people crammed in cities in a short space of time.

Taking another historical perspective, it was only in 1800 that the global population reached one billion, having achieved this feat over a period covering around two million years. By 2050, it is expected that the global total will be more than nine billion. So, pandemics aside, city parks are (very soon) going to be more important than ever.

The health benefits of getting out and about in a green space in an urban setting are not lost on the World Health Organisation, which has been banging the city park drum for years. In 2016, WHO published a 91-page report that highlighted the many and varied ways parks are good for us.

These included “psycho-physiological stress reduction” (connected to the positive effects of being in a natural setting), a boost to “attention retention” (how we handle cognitively demanding tasks), “improved social capital” (being around other people lifts your mood and advances social cohesion), stronger immune systems, better fitness, less obesity, and less inhalation of pollution.

Add to all this more Vitamin D from exposure to sunlight, better sleep, improved mental health, “reduced cardiovascular morbidity”, reduced type 2 diabetes, and “improved pregnancy outcomes” (heavier and healthier newborns), and parks would appear to be key to our wellbeing. They even “enhance pro-environmental behaviour”, says WHO, making us generally more “eco” and better citizens of the planet. Forget an apple day It’s a park a day you really need.

During the pandemic many of us have clearly been doing just that, while enjoying these seemingly endless health benefits, which do not even take account of various other pluses the European Commission highlights in a separate The Future of Cities report: “Urban green spaces can host birds and bees, provide cleaner air, allow water to infiltrate the soil, and reduce the impact of heatwaves.”

They also improve “creativity, entertainment and economic activity”. The more you delve into the positive qualities of parks, the more you wonder why every nation does not have some kind of secretary of state for green urban spaces up there with chancellor of the exchequer or foreign secretary.

Although perhaps no such new positions are required. According to figures from the European Commission, the “greenness” of European cities has increased by 38% in the past 25 years so that now, apparently and astonishingly, 44% of Europe’s urban population lives within 300 metres of a park.

Meanwhile, city mayors across the continent have been focusing on securing more public parkland, just as those ahead-of-their-time city councillors in Valencia were back in the 1950s.

One city, which has faced a related problem and found a similarly advantageous solution, is Nijmegen, in the Netherlands. It is located on a sharp bend on the River Waal which creates a bottleneck and makes the area vulnerable to flooding. To minimise the risk, in the last decade a new two-mile channel has been dug, close to the village of Lent, parallel to the river – the Spiegelwaal.

Between the river and the channel is now a brand new island which – as a byproduct – has given the area a stunning parkland, accessible by bridge. It is called Veur Lent (‘Lent’s front garden’) and offers boating and beaches, as well as a festival area.

Berlin is one of the leaders of the city parks pack with a third of land given over to green spaces including no fewer than 2,500 parks, many in oasis-like spaces that used to be home to industrial sites in East Berlin.

Its showstopper park, however, is Tempelhofer Freiheit Park, which has grown out of the former Tempelhofer Airport, closed to planes in 2008 long after being developed in the 1930s by the Nazis, who built a giant curving limestone terminal (and also used the airport as a parade ground). Now it is a popular, 355-hectare park, with the old runways perfect for ‘kite land-boarding’, cyclists and skateboarders – attracting thousands of tourists each year.

Meanwhile in Paris, estimated to have a mere 9.5% of land in the form of gardens and parks, its eco-friendly mayor Anne Hidalgo has begun converting eight hectares of public space into parkland and ‘urban forests’.

“Wherever possible, in streets, squares, and playgrounds, we are removing asphalt to give space back to nature. With tree-planting programmes, real urban forests will act as the lungs for neighbourhoods across the city,” she says. Among the first of the new parks are the Hans and Sophie Scholl Garden by Saint-Ouen, and Jardin Elisabeth Boselli Porte de Versailles, named after the first female fighter pilot in the French Air Force.

The first “urban forests” are to be in front of the Hotel de Ville, the city hall, and behind Opera Garnier, on a plaza by Gare du Lyon and along a pedestrianised stretch of the River Seine. Tree planting dates for these are yet to be set.

In Copenhagen, one of the world’s greenest cities with an aim to become carbon neutral by 2025, a new 70-acre nature reserve is planned for an industrial area in the North Harbour and parkland has been added around Copenhill, a power station that converts waste into energy. You can even hike onto the roof of this power plant (or, bizarrely, ski down a new artificial ski slope on one side).

A similar “rooftop park” is to be found above the Warsaw University library overlooking the River Vistula, now well-established with trees and banks of plants after opening in 2002. And in Barcelona plans are afoot to turn a fenced-off area with little greenery close to Barcelona Football Club’s Camp Nou stadium and into a terrific 26-hectare park, all part of a scheme to try and fall in line with WHO recommendations that all cities should have a minimum of nine square metres of green area per inhabitant (Barcelona currently falls short with about six square metres).

One European city has put its own spin on creating solving the problem of too few green spaces for its growing population. In Amsterdam, home to a huge, 2,500-acre park known as Amsterdam Forest to the south of the city centre that was established in the 1930s, there is little room for more parks in the packed streets around the main canals.

So a novel approach has been adopted: to bring ‘park life’ into the city, as though turning Amsterdam into one big living park, This evolving policy includes planting green borders along streets and trees wherever possible, closing some roads within the A10 ring road to create ‘green play streets’, and encouraging the adoption of ‘green roofs’ and ‘green walls’ on buildings.

It is clearly a popular (vote-winning) approach, even if it is hard not to speculate on how much is rhetoric. The mayor of London’s office, for example, aims to make more than half of London ‘green’ by 2050.

How precisely this will be achieved is not clear – are houses to be torn down to make way for parks? But it is a reassuringly environmentally friendly sentiment/target that might just be achieved with a bit of jiggling of definitions – private gardens being included and large ‘urban fringes’ recategorized as ‘green’.

As things stand, parks account for about 18% of London’s land – which would not have been boosted all that much had Boris Johnson’s ill-fated and expensive (£43 million) attempt to build a Garden Bridge gone ahead when he was mayor, despite all the grand talk of turning the capital green with a “floating paradise”.

It was walking in London’s largest public green space, the 2,400 acres of Richmond Park in southwest London, during the lockdowns that got me thinking about parks and the importance they play in modern city life.

The result was my new book Park Life: Around the World in 50 Parks in which I took a “voyage of the imagination” around the globe, deep in the travel-impossible lockdowns, remembering favourite green urban spaces from Berlin to Pyongyang, Odessa to Helsinki, Sydney to Cape Town, Quito to New York City (thanks to old notebooks and pictures taken during my 25 years as a travel writer).

It seemed the right time to celebrate the simple pleasures of parks – the wildlife, the landscape, the interesting people you might meet – as well as and the many secret histories they sometimes hold, wherever they may be. The conclusion, after looking back on so many, was simple, too: the greener the city, the happier the city, with Valencia’s Jardin del Turia a wonderful example of getting things right.

Cities, as United Nations figures show, are set to grow yet further. In the past 25 years alone, the world has seen cities increase by an area equivalent to the size of Ireland and this incredible pace is unlikely to slow.

Experts from the EU suggest that cities such as Brussels, Luxembourg City and Stockholm may grow by 50% by 2050, while Vienna, Budapest, Prague, Munich, Bologna and several French regional conurbations may increase between 20 to 50%. Plenty more parks will be needed soon, if we are not all going to go stir crazy the next time a pandemic comes along.

- Tom Chesshyre is author of Park Life: Around the World in 50 Parks published by Summersdale on September 9

TOM’S FAVOURITE EUROPEAN PARKS

National Garden, Athens

38 acres of tranquil parkland in the shadow of the Acropolis, close to the country’s parliament. It was commissioned in 1838 by Queen Amalia and completed by 1840. A German agronomist designed the park and imported over 500 species of plants – many of which did not survive the Mediterranean environment – and animals. While walking in the park in 1920, King Alexander was bitten by a monkey, dying of sepsis three weeks later. His death ushered in a series of momentous events for the region (among them the fleeing of the young relative who would later become the Duke of Edinburgh). Churchill later wrote: “It is perhaps no exaggeration to remark that a quarter of a million persons died of this monkey’s bite.”

Giardini Papadopoli, Venice

A tiny, quiet corner of Venice near the Grand Canal and Venezia Santa Lucia Station. The gardens, once far more extensive than today, occupy the lands of a demolished monastery and were first laid out in 1834. Much of the site was destroyed to create an extension for a bus terminal and the construction of a new canal.

Prater, Vienna

3,200 acres of land by the River Danube, home to the 65-metre Ferris wheel featured in Graham Greene’s The Third Man. The name derives from one of two Latin words (or possibly both): pratum, meaning meadow; and Praetor, meaning magistrate or lawyer. The name came to refer to a wide area along the river, much of which was used as a royal hunting ground. The famous Ferris wheel was the tallest in the world, until 1985.

Tiergarten, Berlin

Bang in the heart of the German capital with lakes and winding paths through woodlands, plus a weekend flea market on one side and tucked away beer halls. Another former royal hunting ground (Tiergarten might literally be translated as deer garden). The area was badly damaged in the war and much of the trees were felled. After the war, occupying British troops turned much of the area over to farmland. A post-war replanting scheme was seen as representative of the country’s wider recovery.

Lazienki Park, Warsaw

Wonderfully peaceful with its monument to Frederic Chopin (free Sunday Chopin performances in the summer), lakes and cafes. This is another European park that began life as a royal playground. In the 18th century, it was transformed by Poland’s last monarch, Stanislaus II Augustus, into a setting for palaces, villas, classicist follies, and monuments. It took the name Lazienki (‘Baths’) from a bathing pavilion that was located nearby.

Oosterpark, Amsterdam

To the east of the city centre, in a multicultural neighbourhood away from the main attractions but with little cafes and bars all around. Its creation at the end of the 19th century required the relocation of a centuries-old cemetery, prompting protests from locals. Part of the cemetery remains in the park, but the rest was moved to Nieuwe Oosterbegraafplaats (New Eastern Cemetery).

Jardin Darcy, Dijon

Close to Dijon’s main railway station, this pretty two-and-a-half-acre park is built above an intriguing, vaulted reservoir. It was built in the 19th century to showcase the city’s drinking water supply system, which had been created by local engineer Henry Darcy and relied on water brought in from a spring around eight miles away. Dijon was one of the first cities to have a modern drinking water supply.

Jardin del Turia, Valencia

An oasis of green snaking through Spain’s third-largest city, formed after the River Turia was diverted after a major flood in 1957. A man-made channel now carries the river south of the city centre, leaving the old course to offer several attractions, including ponds, paths, fountains, flowers, football pitches, cafés, artworks, climbing walls and an athletics track. It is traversed by many bridges carrying traffic across the park.

Jardim do Morro, Portugal

On a hill on the opposite bank of the River Douro to Porto, in Vila Nova de Gaia, with sweeping city views and great sunsets. (The name means ‘Garden of the Hill’). Accessible by cable car, the site features an amphitheatre-like set of curved concrete benches to enjoy the vista. It was established in 1927 – late by the standards of many European parks.

Richmond Park, London

Home to 600 deer with a bloodline stretching back to the days of Henry VIII, plus oak tree woodland, lakes and plenty of quiet corners. In the Second World War it hosted an extensive army base, and some ponds were drained to disguise them as landmarks. Some of the military facilities were repurposed to provide accommodation for some athletes during the 1948 Olympics. Cycling races also passed through during the 2012 Games in the city.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37