Two events, a decade apart. Paris in June 1944 is thrumming with the prospect of liberation. The Allies have landed at Normandy and are advancing steadily through northern France towards the capital. The city is holding its breath, ready to celebrate.

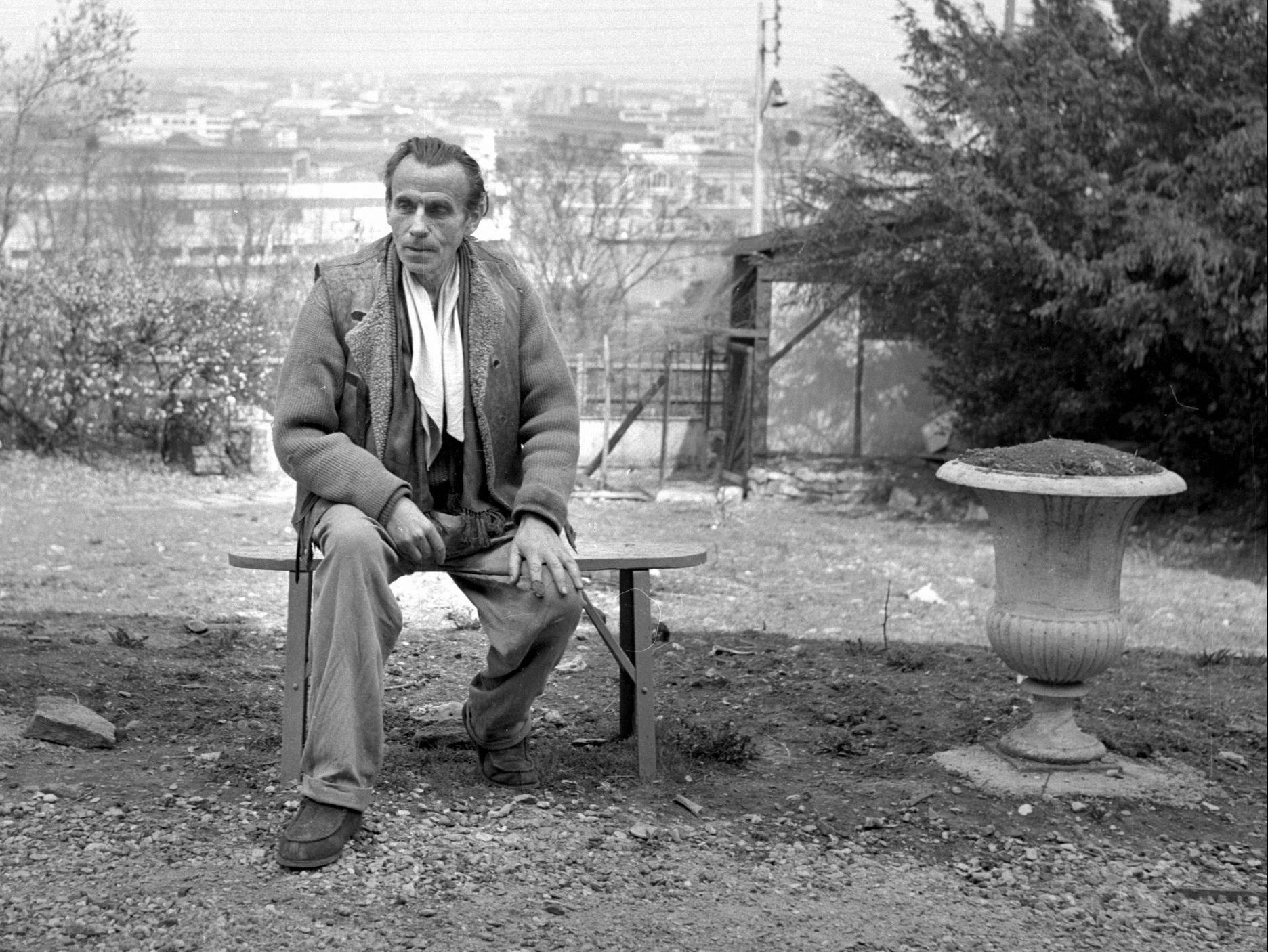

One man not particularly relishing the arrival of liberating forces is Louis-Ferdinand Destouches, physician and, under the pen-name Céline, a literary giant whose 1932 Voyage au bout de la nuit, ‘Journey to the End of the Night’, is regarded as one of the finest works in the history of French literature.

The reason Céline is feeling distinctly uneasy at the prospect of the end of the Nazi regime is that he had established himself even before the Germans arrived as a virulent anti-Semite. As far back as 1937 he’d published Bagatelles pour un massacre, ‘Trifles for a Massacre’, a rampagingly antisemitic work that advocated France’s alliance with Hitler’s Germany in order to eliminate Jewish influence in the country.

Two years later came Ecole des cadavres, ‘School for Corpses’, and in 1941 Les beaux draps, ‘A Fine Mess’, to complete an obscene, spittleflecked trilogy, a book in which Jews, Freemasons, the Catholic Church, the education system and the French army itself were thoroughly filleted by Céline’s raging pen. The books were so extreme even the Vichy regime banned them and death threats were posted regularly through the letterbox of the author’s Montmartre apartment.

On June 17, 1944, Céline puts on an overcoat in the lining of which his wife Lucette has sewn some gold coins, ushers her out of the door, picks up their cat, hurries down the stairs, emerges furtively into the street and bustles off to the Gare de l’Est. Everything he owns is left behind in the apartment. In Celine’s pocket are forged identity papers that will abet the Destouches’ escape to southern Germany, where they will hole up with Philippe Pétain, head of the collaborationist Vichy government, and his cabinet at the castle of Sigmaringen. Almost as soon as his train pulls away, the Montmartre apartment is ransacked.

Ten years later, also in Paris, Simone de Beauvoir watches as her lover Jean-Paul Sartre sits and reads the manuscript of a novella she has just spent three months writing. The year, 1954, will see Beauvoir win the Prix Goncourt for her roman-à-clef Les Mandarins, ‘The Mandarins’, but that spring she isn’t quite sure whether her slim, autobiographical work Les Inséparables, ‘The Inseperables’, is strong enough to follow that 600-page epic.

It’s an intensely personal work, perhaps too personal. She values Sartre’s opinion above all others and effectively leaves him with a casting vote on the book’s future.

The manuscript tells the story of two teenage friends, Sylvie and Andrée, of whom Sylvie is based on Beauvoir and Andrée on her childhood friend Élisabeth Lacoin, nicknamed Zaza, who died of viral encephalitis in 1929 at the age of 21. It was an intense friendship that some speculate might have been a romantic one.

“I loved Zaza with an intensity which could not be accounted for by any established set of rules and conventions,” Beauvoir wrote in her autobiography. “The least praise from Zaza overwhelmed me with joy; the sarcastic smiles she so frequently gave me were a terrible torment.”

In her memoir Force of Circumstance Beauvoir describes how on finishing the book Sartre “held his nose; I couldn’t have agreed more: the story seemed to have no inner necessity and failed to hold the reader’s interest”. The manuscript was thus left behind in a drawer. Two incidents, one city, a decade apart more than half a century ago, yet both find themselves in the limelight today for similar reasons but with vastly differing implications.

From Sigmaringen, Céline managed to make his way to occupied Denmark where, at the end of the war, he was arrested as a collaborator and served 18 months in a Danish prison.

He remained in Denmark after his release and in February 1951 was tried in France in absentia and given a one-year prison sentence, a F50,000 fine and had half his property confiscated.

In April he was granted an amnesty on the grounds he was a disabled veteran of the First World War – his right arm had been badly injured – and in July he returned to France, although not to the Montmartre apartment that had been requisitioned and given to Resistance hero Yves Morandat.

Right up until his death in 1961 Céline complained that several novel manuscripts and a number of other works were stolen when his Paris flat was pillaged. He also retained his intensely paranoid antiSemitism: when Beat writers William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg visited Céline in 1958, they were assailed at the gate by ferocious dogs, animals kept, they learned, to ward off Jews.

It’s taken more than 70 years, but he was right about the manuscripts. For decades Céline scholars and biographers had searched for and speculated upon the whereabouts of the disgraced author’s literary trove, all to no avail.

Then in August this year, Le Monde newspaper ran a story that startled the nation. The Bibliothèque nationale de France, the newspaper revealed, had just authenticated more than 6,000 pages of material handwritten by Céline, the papers removed from Montmartre after his hasty departure as the Allies closed in.

Among the yellowing bundles held together by wooden clothes pegs are three novels, several novellas, revised versions of previous novels and a number of letters and personal papers. In literary terms, it’s a goldmine.

For the past 15 years the manuscripts have resided with a Libération journalist named JeanPierre Thibaudat, who says they were given to him by an anonymous donor on condition that their existence not be revealed until after the death of Céline’s wife Lucette Destouches, as he did not wish for her to benefit from their publication.

Destouches died in November 2019 at the age of 107. Thibaudat has refused to reveal who handed him the cache or where the material was between 1944 and 2006, when it came into his possession.

While the collection is unquestionably worth millions – a few years ago the Bibliothèque nationale de France paid 8m euros for the handwritten manuscript of Voyage au bout de la nuit – there remains the question as to what to do with all this unpublished work.

Céline’s legacy is mixed to put it mildly: some say his literary brilliance permits the work to be judged separately from the man, others that his hideous track record of antisemitism should condemn him to as much obscurity as posterity will allow.

When a decade ago Céline was slated for inclusion in the 2011 annual Recueil des Célébrations nationales, ‘Compendium of National Celebration’, to mark the 50th anniversary of his death there was an outcry that led not only to his removal from the book but the title of the publication itself being changed to Livre des Commémorations nationales, ‘Book of National Commemoration’, the name by which it has been known ever since.

The Thibaudat papers promise a row to make that contretemps seem like a polite disagreement.

In the meantime, no such brouhaha surrounds the publication of another lost work, Simone de Beauvoir’s Les Inséparables. The novella, criticised by Sartre and deemed ‘too intimate’ to be published during her lifetime finally appeared in France last year and this month sees it published in the UK in Lauren Elkin’s elegant, sensitive translation. For Sarah Ditum in the Spectator, The Inseparables is “quite perfect”. Of Sartre’s rejection of the original manuscript Boyd Tonkin in the Times wrote, “Not for the first or last time, Sartre got it wrong”.

Newly-discovered work by a deceased author is always an exciting moment. Sometimes, as in Beauvoir’s case, their publication is absolutely justified. Cold Comfort Farm author Stella Gibbons’ Pure Juliet, found by her family 25 years after her death and published in 2016, was universally well-received, for example.

Other posthumous publications are more questionable, such as Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman, a prelude of sorts to To Kill a Mockingbird that the author herself had shown no interest in publishing during her lifetime but which appeared with what some regarded as indecent haste after her death in 2016.

Céline’s legacy, mixed with a strong and vocal lobby in France that demands great literature stand on its own whatever the sins of the author, is far more complicated and guarantees fierce argument for years to come.

Whatever the quality of the lost work, can it ever expunge the memory of three of the most horrific, bigoted treatises ever written against a group of people? Can the sympathy for the marginalised on which Voyage au bout de la nuit was constructed, winning the book so many admirers, now ever be seen as anything other than a hollow pretence?

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37