What happens when none of the parties win and each of the parties is disappointed with their performance? That is the big take-away of Germany’s dramatic but ultimately frustrating first election of the post-Merkel era.

Two hours after polling stations closed their doors and the first exit polls were published on Sunday night, the seven candidates gathered in a TV studio for the “elephant round”, a traditional fixture of German elections in which the big beasts are invited to set out their opening negotiating positions.

They all looked miserable, as well they might.

The hapless Armin Laschet, Merkel’s heir apparent, grimaced when invited to take personal responsibility for the Christian Democrats’ worst performance in post-war history.

For all the positive spin she tried to put on her parties’ results, the Greens’ Annalena Baerbock knows that she is being blamed for failing to take opportunity of the huge surge in popularity she received on her appointment as candidate in spring.

Christian Lindner, the flashy but ultimately vacuous leader of the liberal FDP, who forsook the opportunity to go into government with Merkel four years ago, won’t make the same mistake again. He saw only the tiniest increase in his party’s vote.

On the two extremes, both the far-right AfD and the left-wing Die Linke fell back sharply.By a process of elimination, Olaf Scholz should have been smiling.

The obituaries of the Social Democrats had long before been written. The party was supposed to be dead on its feet, representing a union-based, ageing and ultimately disappearing slice of the electorate.

Instead, it ended up with the highest share of the vote, ahead of the CDU by around two percentage points.

It was a remarkable turnaround. Within weeks of the start of the campaign, the SPD vote gradually rose.

Scholz said little of interest at any point, but, unlike his rivals, he made no mistakes. He played safe, posing as Merkel’s doppelgänger, even though he belongs to a different party.

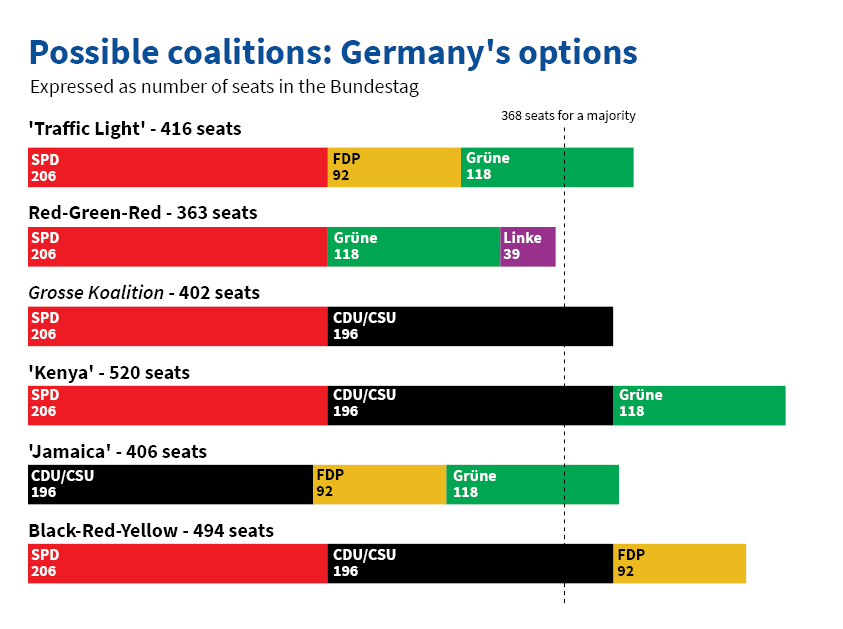

The bigger problem Scholz faces is that one of the potential coalition partners, the FDP, is reluctant to go into government with the centre-left.

The Greens could go either way and will play the big parties off against each other.

That is why these two smaller parties are being called the kingmakers. They are talking to each other first.

If they can settle their own differences – and there are many, on higher taxes, minimum wage, not to mention climate – they will be an unmovable force.

They share similar voters, better educated, younger and more urban, and so the pressure will be on Lindner and Baerbock, and the Greens’ co-leader Robert Habeck, who will now be the party’s most powerful voice, to find a way through.

They might yet opt for an alliance with the CDU, but the chances of that are slim.

For Laschet it is coalition or bust. He would go down in history as one of the CDU’s shortest and most ignominious leaders. Hence, he would be tempted to offer just about anything to entice the other parties to join him.

They know that, but they also know that he has little authority or credibility left.

Either way, this will be a three-party coalition and will not be assembled quickly. Asked whether Merkel would still be around to give her 17th annual New Year’s televised address (something she hates doing), the candidates said they hoped to get it done by then but couldn’t guarantee.

These elections have highlighted the many contradictions of German society.

Voters crave predictability in politics but have produced the most unpredictable and fragile of results.

Theirs is a politics of contentment in a country that never seems content.

They look around and see a country held back by bureaucracy and a failure to modernise. (I take a particular pleasure in reminding Germans that their broadband speeds are slower than Albania’s).

They are desperate for change but are also frightened by it. They know that Merkel’s time was long up, but also know they are going to miss her deeply.

This will now be a rougher ride. “Germans have to learn how to argue,” Karl-Rudolf Korte, one of the country’s top political scientists, tells me. “They have to realise that politics is about more than administrative problem-solving.”

For the next several months, everything will change, and nothing will change.

Merkel will stay on as the boss. If she makes it to December 17, she will overtake Helmut Kohl as the longest-serving chancellor of modern Germany. Not that she is hanging on in the hope of achieving this landmark.

She has made it clear, time and again, she wants out, to tend to her garden and not to have manage any more crises that befall the country.

Before she goes, she will have to oversee the G20 and the hugely important COP26 climate change conference in Glasgow. In January, Germany will take over the G7 from the UK with either an inexperienced or an interim government.

Europe and the wider world need a strong Germany as a bulwark of democracy and reason in an era of uncertainty.

In Merkel, it had a leader who gave them stability but in so doing sucked some of the lifeblood out of politics.

The going is set to get bumpier.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37