Angela Merkel’s first G7 Summit as German chancellor was a G8, at which Russia’s status as a full member of the political and economic elite was confirmed. It is a sign of Russia’s fallen standing that G8 is today G7 again; yet also a sign of Vladimir Putin’s hold on Russia that he will soon be the only leader from that 2006 St Petersburg gathering still in power. Bundestag elections September 26, followed by new coalition formation, and the Merkel era is over. Putin has seen them all off.

There she is, in the official photo outside Constantine Palace, in trademark uniform of plain jacket and dark trousers, sandwiched between Italian PM Romano Prodi, who left office two years later, and Tony Blair, who would be gone within a year; Putin is centre stage between French president Jacques Chirac (RIP) and US president George W Bush, now a painter more than a politician. Japan’s Junichiro Koizumi and Canada’s Stephen Harper complete the G8 line-up.

Putin has stayed in power through a mix of political skill, constitutional trickery, and thuggish methods more suited to dictatorship than democracy. By contrast Merkel, in winning her four terms as chancellor, never lost sight of the special responsibility upon a post-war German leader to uphold democratic, constitutional values.

Friend and enemy alike must also recognise that staying in power for sixteen years, in a genuine democracy with a complex electoral and political system, puts her in the top league of political operators. She is on her fourth US president; her fourth French president; her fifth British prime minister. It would be somewhat out of character for her to write a no-holds-barred memoir, but my God it will be worth reading if she does.

As Germany looks towards the post-Merkel era, it does so with some anxiety, for her strengths are not easily transferable. The ‘Mutti’ nickname, which began as a complaint from MPs who felt she was too controlling, stuck as a positive in the country, to which she emanated a sense that whatever the problem, she would solve it. It was a remarkable political achievement, for it made most Germans, including millions who didn’t vote for her CDU party, feel it was nonetheless best for Germany if she remained as Chancellor.

‘Alternativlosigkeit’ – lack of alternative – was named ‘most hated word of 2010.’ It is partly what led the right-wing AfD to call itself Alternativ für Deutschland. Yet had she chosen to stand for a fifth term, the chances are she would have won, and part of the anxiety for her party is that CDU Chancellor candidate Armin Laschet is seen as something of a lightweight not merely alongside Merkel, but alongside those he defeated in the race to get his name on the ballot.

She came to represent stability, even amid a succession of huge crises – eurocrisis, global financial crisis, refugee crisis, finally Covid. The jury is very much out on whether she handled the last of these well. The complexities of Germany’s political system, and lack of progress on digitalisation, exposed weaknesses perhaps long in the making.

It was also unfortunate that the crisis coincided with the period when the so-called Union of the CDU and its Bavarian sister, the CSU, was choosing its candidate to replace her. Laschet, Bavarian minister-president Markus Söder, Friedrich Merz and others seemed to be using the crisis for positioning and profile-building in their internal battle. In winning it, Laschet put himself deliberately at odds with Merkel, which may have explained her decision largely to stay out of the election campaign, a decision she reversed last weekend to express support for Laschet as he continued to slide in the polls. Likewise, Söder’s current stance of total support for Laschet sits oddly with both word and deed prior to Laschet’s crowning as candidate.

Initially, Merkel had singled out Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer as her chosen successor, but a mix of errors made, and internal battles lost, led to ‘AKK’ learning the hard way that Merkel support is always conditional. According to a gripping, highly critical new book, Macht Verfall (literal translation ‘Power Decay,’) by German journalist Robin Alexander, when she finally pulled the plug, Merkel commented to a colleague that she can put people in the right position, “but they have to be able to walk on their own.”

If someone cannot last the course, it is their fault.

Perhaps that is what is at the heart of the current German anxiety about what and who comes next. Merkel did a lot of the walking for everyone. She knows how to last the course. But maybe Mutti mothered the CDU so much it doesn’t quite know how to manage without her.

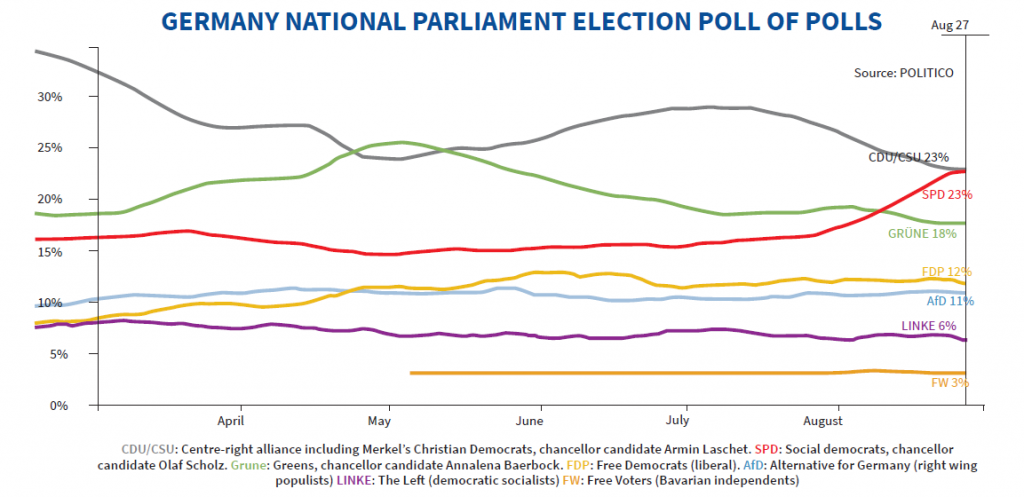

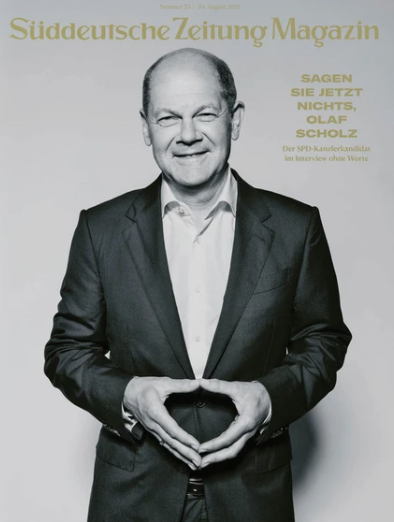

With the Greens’ campaign having stalled from the high point of Annalena Baerbock’s appointment as the party’s first-ever chancellor-candidate, the once-mighty but recently anything-but-mighty Social Democrats appear to be back in the game, and SPD chancellor candidate Olaf Scholz now genuinely in the running for the country’s top job.

Perhaps the enduring lesson of the Merkel era is the German yearning for stability. And a strange political irony may be developing – that Germany sees that stability less in Merkel’s successor as CDU candidate, the affable but gaffe-prone Laschet, and more in the dry and rather dull Scholz, who has served as finance minister and vice-Chancellor in her latest coalition government.

Campbell

Scholz is clearly aware of the Merkel power even as she leaves. His latest campaign poster has emblazoned across his photo the very clever play on words ‘Er kann Kanzlerin.’ ‘Kanzler’ is the German word for Chancellor. ‘Kanzlerin’ is the feminine equivalent, the one Germany has been used to for sixteen years.’ It is basically saying ‘He can be Merkel’!

Momentum is so important in a campaign. Baerbock had it, and has lost it. Laschet has never really had it. Last week a poll showed the SPD ahead of the Union for the first time since Merkel beat the SPD’s last chancellor, Gerhard Schroeder, fifteen years ago. Scholz has even taken to holding his hands in what has become known as “the Merkel Rhombus.” She does it to indicate calm. He does it to indicate to Germans, “if you want to see Merkel in your successor, then look no further than me.”

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37