I first met Ernest Hemingway in Spain, at a small resort on the Costa Brava north of Barcelona. I had just turned 16 and he had been dead 25 years.

He was waiting for me at the back of a Tossa de Mar mini-mart, beyond aisles of raffia beach mats, souvenir ashtrays and tanning oils, on a shelf of foreign language paperbacks. The Dangerous Summer, a slim account of a bloated last European hurrah for Hemingway; the author as bullfight groupie questing through Spain in 1959 in the wake of a couple of hotshot matadors.

Poet Charles Bukowski once described how the walls of the Los Angeles Public Library trembled as he pulled a volume of his great influence John Fante from the shelf for the first time. Same here. As my finger settled on that Hemingway spine, an under-inflated lilo creased over, limp in the breeze. The moment I touched that book, life changed.

That early summer day in Tossa, I began to traverse the wide spectrum of Hemingway obsession, a journey that turned into my own mad quest to understand this strange writer, strange man.

It wasn’t the most auspicious start to a lifelong fascination. The Dangerous Summer is just dreadful, full of insane sentences like this: “Then he raised his hand as he faced the bull and commanded him to go down with the death that he had placed inside him.”

Bullfighting, bullshitting; by this very late point in Hemingway’s career it was all pretty much the same. To borrow the immortal phrase of Top Gun’s Captain Tom ‘Stinger’ Jordan, Hemingway’s ego was writing cheques his body couldn’t cash. Just a couple of years after his dangerous summer in Spain, he was dead by his own hand.

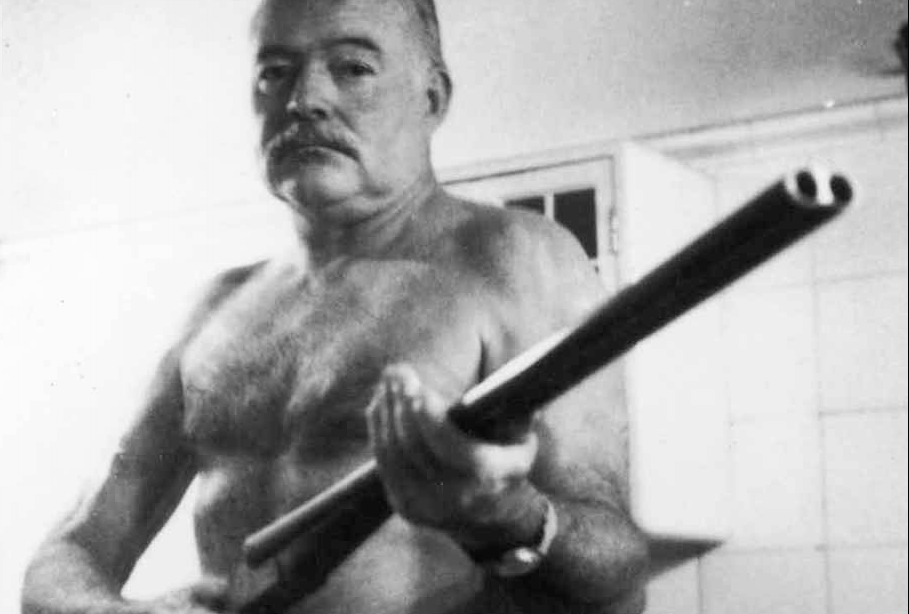

This, one might think, could be interpreted as a warning. After all, blowing your brains out with a duck-hunting rifle is not usually an indicator of a man relishing life the way Hemingway apparently did.

Far from it. The suicide of Ernest Miller Hemingway added to his appeal. He may have left it a bit late, but his death still contained something of the live-fast-die-young romance of a James Dean or a Jim Morrisson (both of whom I was equally obsessed with).

Even in the posthumously cobbled-together The Dangerous Summer, there was something powerful enough in the residue of this great writer’s talent to take a hold of me that would last to this day. Not just the words but the epic, exotic and ultimately tragic swagger of the man. More than enough for a shy teenager from the gloomy and wet north-west of England to lose himself in.

One thing The Dangerous Summer captures well is the old republican’s excitement at returning to his beloved Spain, a country he had long thought shut to him so long as the fascist Franco drew breath.

European discovery was central to the Hemingway story, since signing up age 17 as an ambulance driver for the Red Cross at the Italian front in the First World War. Getting his legs half blown up while handing out chocolate at the front, and being left heartbroken by the rejection of his nurse, didn’t put him off. For a boy from the right side of the tracks in Chicago, there has never been a writer more obsessed with life in Europe.

His oeuvre may not be entirely European, but this continent dominates all his major novels; The Sun Also Rises (France, Spain), A Farewell to Arms (Italy), For Whom the Bell Tolls (Spain) and Across the River and into the Trees (Italy).

Hemingway came to define our image of Europe in the 1920s; a lost generation carousing through France, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, in search of… well, they never seemed to know exactly what it was they were looking for, but had a strong hunch it would be found in the next town along, or at the bottom of a bottle.

Though the themes Hemingway explored relentlessly are dark – death, loss, courage in the face of inevitable death and loss, more death, lots more loss – the canvasses he stretched for their telling were vivid with adventure and discovery.

The writing itself was a revolution. The construction of those very ordinary sentences with those very ordinary words could wind you. More literary criticism has been expended on Hemingway than any other modern author. He’s been damned as a “major stylist and minor novelist” and praised as the “most outstanding author since the death of Shakespeare” (John O’Hara, no less, in the New York Times). But the quality of the prose in the best of his work, is undefinable. There’s some kind of magic at work.

Hemingway’s heroes – overseas, multicultural, alpha males – were exciting enough, but the author himself was a blockbuster, bigger than any of them.

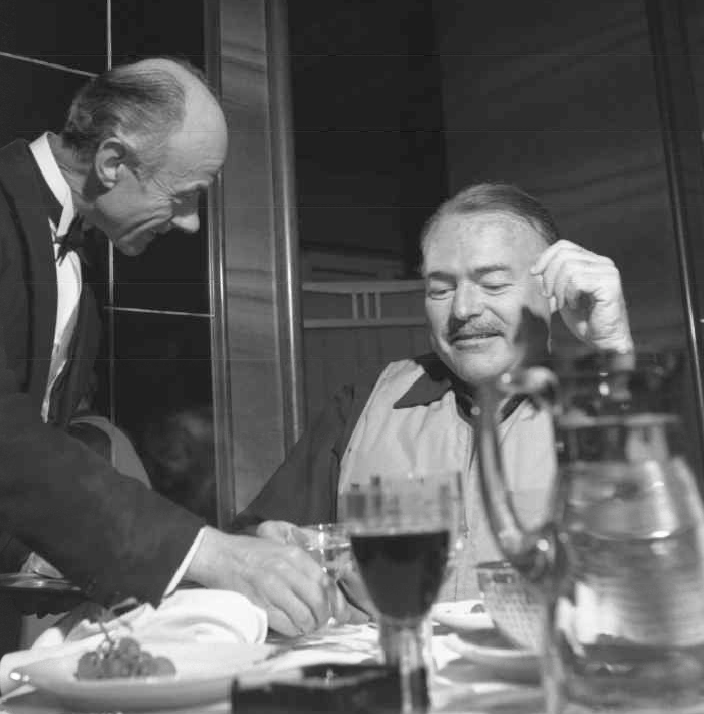

Blown up in Italian trenches; boozing in Paris with Fitzgerald and Joyce and Picasso; running with bulls in a little town nobody had ever heard of called Pamplona; landing record catches of marlin in the Gulf Stream; besieged in Civil War Madrid; organising U-Boat seek-and-destroy missions from his fishing boat; boxing and braggarting and boozing in Sloppy Joe’s; killing lots and lots of very big animals in Tanzania; emerging from jungle plane-crashes to find his obituary on front pages around the world; flying bomber raids with the RAF; commanding a troop of French guerilla Maquis; liberating the Ritz Hotel in Paris from the Nazis; downing ducks in Idaho with Gary Cooper; downing daiquiris in La Floridita with Spencer Tracy and Marlene Dietrich; four wives, a Pulitzer and the Nobel Prize for Literature. Busy boy.

Even if a lot of it was self-promotional baloney (and a lot of it was), there was enough material crammed into a mere six decades for a dozen men to have shared between them. He seemed positively gluttonous in his appetite for life. Right to the moment of his suicide, 60 years ago this week in his mid-century modern home in Ketchum, Idaho.

President Kennedy’s hot-take on news of Hemingway’s suicide in July 1961 – “he almost single-handedly transformed the literature and ways of thought of men and women in every country in the world” – sounds silly today, but at the time it accurately conveyed the magnitude of shock the world felt at his unexpected exit.

The subsequent slew of biographies – Carlos Baker’s being the earliest, most entertaining and most misleading, the most comprehensive being Michael Reynold’s five volumes and the most interesting perhaps being Paul Hendrickson’s Hemingway’s Boat – are unconvincing on how everything that had been so good could turn so bad, so quick.

Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s six-hour, three-part documentary on Hemingway broadcast this week on the BBC is much better at portraying the chronic collapse of a man whose public life was at odds with the tormented existence he endured.

In truth, Hemingway’s was a short and unhappy life. Burns and Novick reveal an often brutish and bullying, sexually-repressed, paranoid maniac, often violent towards those closest to him; possessed of a bottomless professional jealousy, a hatred for his mother and haunted by his own father’s suicide by gunshot; above all, a man on the run from himself, bedevilled by unmeetable expectations of himself, which he would live up to or die trying.

He took everything, most especially Ernest Miller Hemingway, way too seriously. Sure, it had its moments, but life inside his head really wasn’t all that much fun, however the endless publicity photographs made it appear.

This most photographed author of all major 20th century writers rarely let the mask slip (by way of evidence I scoured the global photographic agency Getty Images. Contained within are 2,622 photos of Norman Mailer, 2,263 of James Baldwin, 1,521 of Virginia Woolf, 1,894 of F Scott Fitzgerald, 1,891 of Harper Lee, and 1,124 of Graham Greene. Hemingway beats them all with 2,733 images).

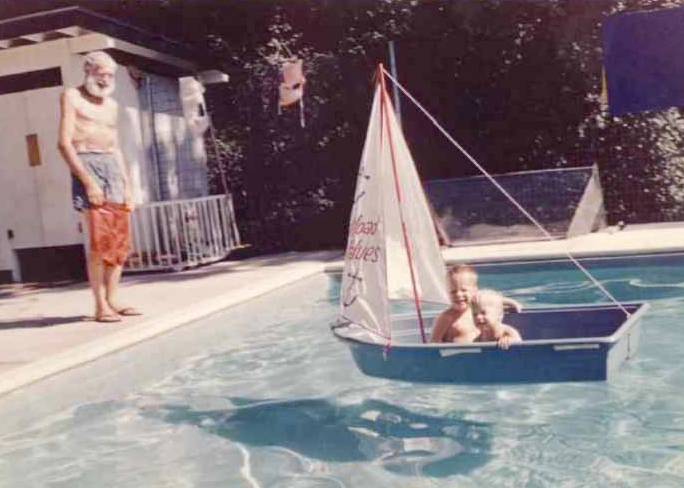

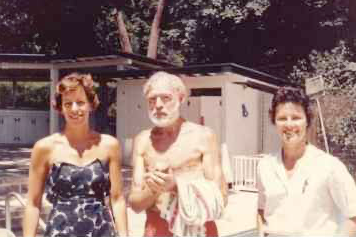

I thought I’d seen them all, yet in the act of searching the Getty archive, three photographs startled me. They are published here for what might well be the first time in decades, if ever, and give a snapshot of just how little of that public Ernest Hemingway was left at the end.

Unposed, garish Kodachrome snaps taken poolside at the family home of a doctor from the Mayo Clinic where Hemingway had been secretly receiving electroconvulsive therapy for depression and paranoia.

Throughout his life, the camera lens was always kind to Hemingway. With his heavyweight boxer’s build and matinee idol grin, here was a colossus of both modern literature and modern life. Even after death that sense of enormous scale prevailed; the press photographs of his strangely ordinary burial reveal the huge polished casket of a fallen giant.

But here, in these snaps, the giant is shrunken and withered. Sagging skin separates bone and his old man’s biceps. The snowy destitute beard. Fragile as perished elastic, he looks like a man in his mid-nineties. He’s 61, just weeks from killing himself.

This was the Hemingway that stared back at him in the bathroom mirror each morning in his few weeks of release after kidding the doctors at the Mayo Clinic he was cured.

When Hemingway applied the final, final full stop of his story with the same shotgun he used for duck-hunting with Coop, this was all that was left. Today, there’s even less.

A little thing like a fatal gunshot was never going to get in the way of the Hemingway industry for long. His reputation – already on shaky ground during his lifetime, particularly after the publication of the derided Across the River and into the Trees and before his Nobel-winning comeback novella The Old Man and the Sea – has suffered for it.

Trash that should have stayed on the cutting room floor where Hemingway left it, has been spliced together and delivered to the world as though the great man was still banging away on the old Royal Portable, wherever it is Roman Catholic suicides end up these days.

The titles are the only decent thing about most of them – Hemingway was, and for my money still is, the best composer of titles in the business. True at First Light, The Garden of Eden, Islands in the Stream… all post-mortem exercises in the extraction of value from a dead author famously neurotic about the quality of his published output. Hemingway’s legacy deserved better than his executors were prepared to sacrifice by way of lost royalty opportunities.

The one good thing published after his death, A Moveable Feast, is a dreamily romantic portrait of life in Paris as a young man, before success and wealth destroyed the ambition and poverty a sentimental Hemingway remembers as defining the happiest days of his life.

The title, chosen by his last wife Mary comes from this sentence: “If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.”

Nobody chooses these things that attach themselves to us, and stay with us the rest of our lives. It’s all an accident, happy or otherwise.

Though Hemingway’s influence on me has, at times, felt overbearing and not always improving, I guess on balance I’m glad it was a Hemingway I picked up in that Costa Brava book store.

It could have been much worse. Next to it was a Jeffrey Archer.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37