After Lionel Messi renewed his contract with Barça in 2017, the club’s head of legal services, Román Gómez Ponti, sent CEO Òscar Grau an email that consisted of one word: ‘ALELUYA’, with the final A repeated 69 times. Grau replied: “The extension of Leo Messi… was important for the survival of FC Barcelona.”

The three separate contracts written by the club guaranteed Messi an annual salary of over 100m euros, according to a document obtained by Football Leaks and passed to Germany’s Spiegel magazine. One internal club document recommended, “The player needs to be aware of how disproportionately high his salary is relative to the rest of the team.”

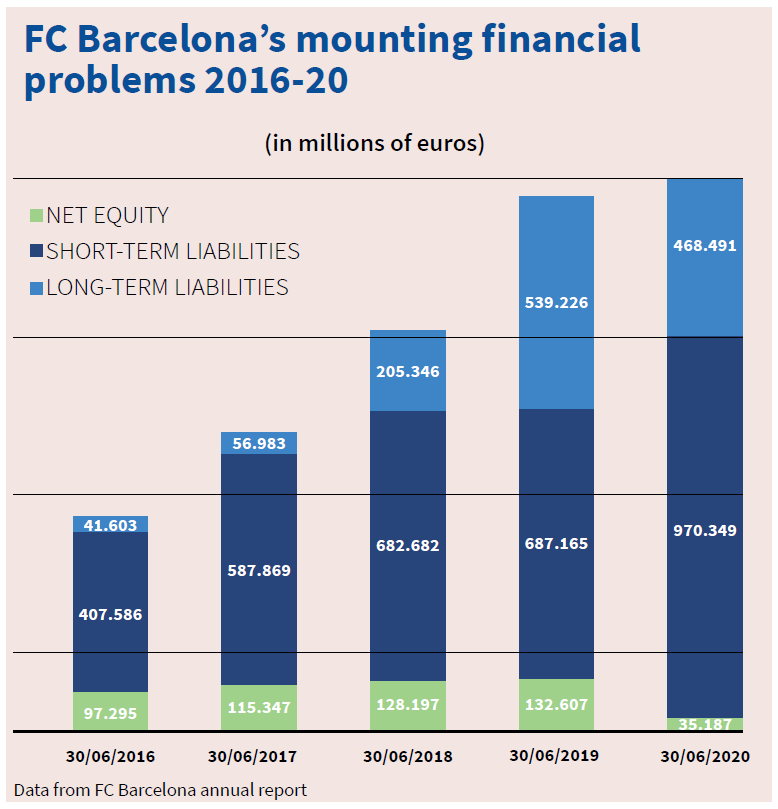

Indeed: Messi was earning about as much as a typical top-class team of the time. Pretty soon, Barça was paying him even more. Aided by the release clause in Messi’s contract, which allowed him to walk out of the door free at the end of each season, his father Jorge negotiated large annual pay hikes. Over the four years from 2017 to 2021, the player earned more than 555m euros (£470m) in total, according to highlights from his 30-page contract published in El Mundo.

Barça and Messi announced they would sue the newspaper, and Messi made plans to sue the five senior Barça officials who were in a position to leak the contract, but nobody denied the figure.

Bayern Munich’s chairman Karl-Heinz Rummenigge said he had “had to laugh” when he saw the contract. “I can only compliment him on managing to negotiate such an astronomical salary.”

A senior Barça official told me Messi’s salary had tripled between 2014 and 2020. He added: “Messi is not the problem. The problem is the contagion of the rest of the team.” Whenever Messi got a raise, his teammates asked for one as well.

After about 2015, Barça morphed from ‘més que un club’ into Messi’s club. ‘Messidependencia’ is an old concept in Barcelona, but originally it described an incidental phenomenon: Messi winning a tight match. Over time, Messidependencia became the system. Barça parasited off Messi, until he began eating the club.

Then, in 2020, sporting disaster, economic disaster and Messi’s decision to leave all struck at once.

During Messi’s first decade in the team, Xavi and Andrés Iniesta had enough status not to give him the ball too early in an attack. They would build on the other flank, waiting for the moment when they could switch across and put him one-on-one against a defender.

But as the duo faded from the team, and Neymar left, Barça’s strategy simplified into Messidependencia. From 2017 until 2019, Messi’s shots and assists accounted for between 45 and 49% of Barcelona’s annual expected goals, calculates the data journalist John Burn-Murdoch.

Almost the only other big modern club more reliant on a single player was Real Madrid (with its Ronaldodependencia) in 2014/15. One level below that, Lucas Pérez was practically a one-man team for Deportivo La Coruña in 2015/16.

Barça’s system became ‘get to the final third, then give the ball to Messi, wherever he is’. They were starting to resemble Argentina, without a shared passing language, playing simple, playground football.

Barcelona’s first team was abandoning Barcelona football. That made it harder still for boys from the club’s Masia academy to make the leap to the Camp Nou. Even if they got the chance, they landed in an alien system. Instead of Messi moving as part of a fluid collective, now his teammates simply reacted to his moves. Most were awed by him.

The midfielder Frenkie de Jong told me: “Messi’s really much better than the other players. I think people underestimate that. They see it every week, and eventually they start to find it normal. You’re playing here with the very best players in the world, in principle, but he’s quite far above that. You have to make sure you’re always trying to keep an eye on him, so that when you get the ball you know if he’s free or not.”

Meanwhile, although nobody at Barça wanted to talk about it, the king was growing old. Messi (and for the most part, Luis Suárez) stopped defending – an almost unheard-of privilege in top-class football. When Barça lost the ball, Messi would often trudge back alone, yards offside behind the opposition’s defenders, watching play unfold at the far end of the field.

Teammates like Ivan Rakitic, Arturo Vidal, Sergi Roberto and Antoine Griezmann acted as his legs, pulling 40-yard sprints to cover the holes he left. That dragged Barça’s midfield out of shape.

As the team aged with Messi, Barça’s training sessions slowed down. This was a shock for Griezmann, who had come from Atlético Madrid. There, he recalled: “Every training session was at the intensity level of a match.” To the quiet dismay of Barça’s younger players, football’s most demanding rondo descended into a warm-up routine.

In matches, Barcelona’s defenders and midfielders rarely overlapped any more. This went against the grain of modern football. The sport continued to evolve weekly, and the one-time innovators Barça were being overtaken.

The economist Joseph Schumpeter labelled the same process in business “creative destruction”: new entrepreneurs come along with new ideas, and the pioneering systems of yesteryear are junked. “Every day football gets more spectacular, the players physically, technically and tactically stronger,” remarked Barça defender Gerard Piqué. “I always say that the best defenders in history are those of today.”

Even Franz Beckenbauer, he added, was “worse on the ball, slower and understood the game less well” than Piqué’s generation. As for defenders who just kicked people, they had died out.

Piqué was right that football kept improving – but only outside Barcelona. While Barça neglected pressing, other teams updated it.

‘Gegenpressing’, the Germans called the latest version: chasing up the opposition the moment you lose possession, so as to win the ball near their goal, before their defence can organise. It was Ajax’s ‘hunting’ of the 1970s on fast-forward – a game so rapid it should be called ‘storming’.

Storming teams adopted some of Barça’s innovations, such as Pep Guardiola’s five-second pressing rule, but discarded others, like the obsession with possession. Whereas Guardiola’s Barça had hated losing the ball, for teams like Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool, losing the ball and then winning it back was the strategy.

Barcelona’s struggles on the pitch saw the sacking of manager Ernesto Valverde in January 2020. His replacement Quique Setién lasted only seven months before he was dismissed in the wake of an 8-2 loss against Bayern Munich in the Champions League – the first time in 74 years the club had conceded eight goals in a game. Next in was former Dutch international Ronald Koeman, who had played for Barcelona in the 1990s.

As the son, brother and father of professional footballers, Koeman had spent his life in a competitive environment. Messi didn’t scare him. The coach arranged a meeting at his captain’s house. Messi returned from Cerdanya on the Franco-Spanish border, where he was holidaying with his family and those of Suárez and Jordi Alba, to lay out his grievances with Barça.

Koeman replied that he only controlled the first team, and reportedly told Messi: “Your privileges in the squad are over, you have to do everything for the team. I’m going to be inflexible.”

Dutch directness had encountered Latin etiquette. Messi was offended – nobody spoke to him like that – and more so when Koeman then informed Suárez in a one-minute phone call that he was no longer needed.

Worse, nobody from the board rang the Uruguayan to thank him for his 198 goals for Barcelona. Messi could accept Barça’s decision to discard his best friend, but he couldn’t forgive the disrespect.

It hardly mattered anyway. Messi was planning to leave the club regardless, as he had told club president Josop Maria Bartomeu several times that year. Bartomeu had always asked him to wait, assuring him that if he still felt that way when the season ended, he would be free to go. Messi later explained his reasoning to the website Goal.com: “I thought the club needed more younger players, new players, and I thought my time at Barcelona was over. I felt sorry because I’d always said I wanted to finish my career here. It was a very difficult year. I suffered a lot in training, in the matches and in the changing room… The moment came when I decided to look for new ambitions.”

The one thing he had always wanted, he said, was “a winning project”: “And the truth is that there hasn’t been a project or anything else for a long time. They juggle and cover the holes as things come up… I want to compete at the highest level, win titles, battle in the Champions League. You can win or lose, because it’s very difficult, but at least you have to be competitive and not melt down like we did in Rome, Liverpool or Lisbon.”

“Leo’s big problem is that he competes with himself,” according to Barça’s former keeper and sporting director Andoni Zubizarreta. Messi had been carrying around the responsibility to win matches for 15 years, explained ‘Zubi’: “We have all had that responsibility. When you’re in the tunnel about to go out to play, you know who the good ones are in your team, the ones who’ll win it for you, especially in finals… A day comes when you look in the mirror and you say, ‘Ooof, this isn’t going to be so easy’.”

A male athlete of a previous generation might have made the decision to change clubs without worrying what his wife and kids thought. After all, Daddy’s job came first. But today’s sportsmen are from a generation of involved fathers.

When seven-year-old Thiago asked his father whether he was leaving Barça, Messi couldn’t bring himself to tell him he might have to make new friends at a new school. Thiago cried anyway, and said: “We’re not going.”

At the family meeting where Messi broke the news, his wife and three sons all burst into tears. “It was a drama,” admitted Messi later. Nonetheless, on August 20 he sent Barcelona a ‘burofax’ – a sort of registered letter carried by the Spanish postal service – officially stating his decision to go.

The Messis knew that his contract specified he could only leave on a free transfer if he announced his departure by June 10. However, a cavalier lawyer assured the family that the deadline wouldn’t apply in the special circumstances of 2020.

What the clause really meant, the lawyer said, was that Messi had to announce his departure soon after the end of the season. It was a mere quirk of fate that in 2020, uniquely, the season ended in August. Messi was sticking to the spirit of the agreement, said the lawyer, who was no doubt eager to come up with an interpretation that would please the great man.

The family seems to have accepted the assurance unthinkingly. Messi himself was sure he was free to go. Hadn’t Bartomeu always told him to decide after the season?

Like Cruyff before him, Jorge Messi (Lionel’s father) had succumbed to the fantasy that he was a brilliant businessman who could negotiate huge contracts alone. Yet in the biggest decision of his son’s career, with hundreds of millions of euros at stake, the family displayed the amateurism of a mom-and-pop shop.

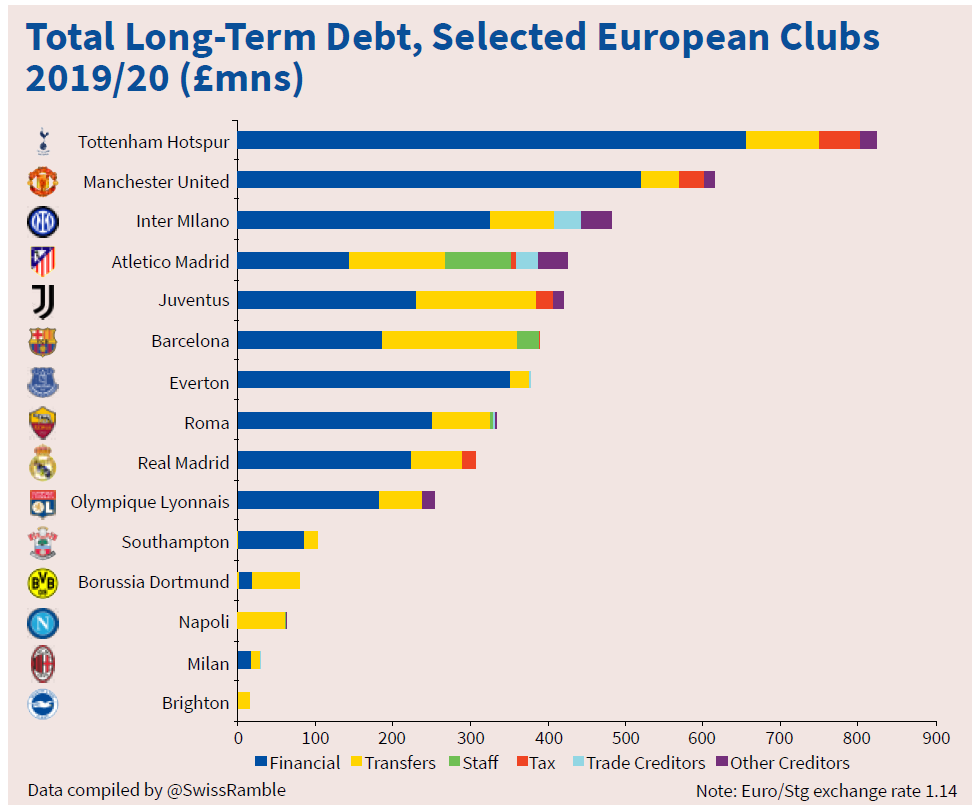

The Messis’ counterparty, Barça, wasn’t thinking like a business either. Had it been a more corporate club, a Catalan Manchester United, it might have met the family halfway: pointed out that the deadline for a free transfer had passed, but let Messi leave, probably for Manchester City, for a fee of about 200m euros (£170m).

By also shedding his salary, Barça would free up a total of over 300m euros (£254m) to rebuild the team. It would have been the pragmatic decision. After all, Messi, then 33, was free to walk out the door ten months later for nothing, while pocketing a hefty loyalty bonus.

But Barcelona isn’t a business. It’s a neighbourhood club run by local merchants who plan to live in town until they die, and who care above all about their reputations there.

Bartomeu, already despised for his disastrous transfers and conflicts with players, wasn’t about to become the president who lost Messi.

With masked demonstrators outside the Camp Nou demanding his resignation, he said the player could only leave if a club paid his release clause of 700m euros (£592m). No club was going to do that.

That was when Messi gave in.

The compromise reached last summer did not last and this month Lionel Messi ended his 18-year relationship with Barça.

He had been negotiating a new deal which would have included a salary reduction of 50%. However, Barcelona were unable to complete the necessary financial restructuring to get the deal over the line and reduce the club’s wage bill to stay within La Liga’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations.

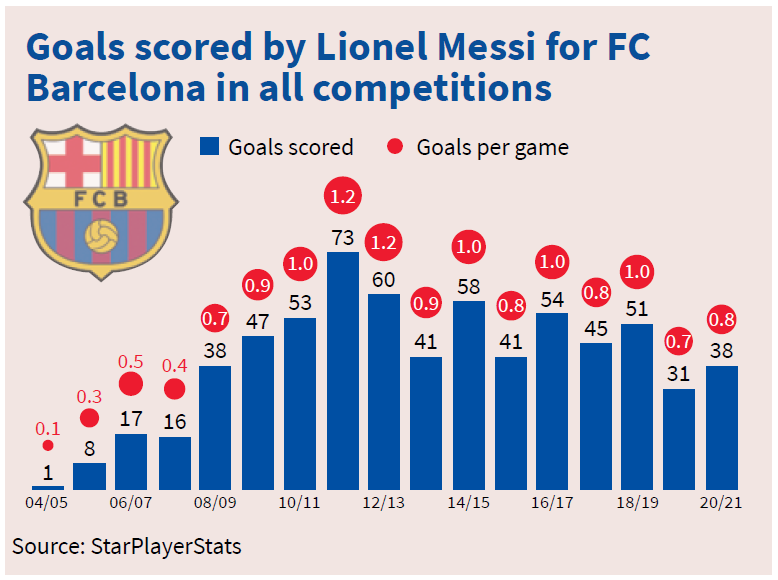

After 778 games and 672 goals, six Ballon d’Ors and 35 trophies – including four Champions League titles – last week Messi became a Paris St Germain player.

- This is an extract from Barca: The inside story of the world’s greatest football club, by Simon Kuper (£20, Short Books)

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37