There is a song in the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical Cats about getting away with mischief.

Two elaborately named feline miscreants – partners in crime – explain that when their theft, destruction or other misdeed gets discovered, the humans always ask the same question: “Was it Mungojerry? Or Rumpleteaser? And most of the time, they leave it at that.”

It is very much the same with the Boris Johnson government. Faced with any particular crisis they have a choice of two culprits to blame – and nothing need ever be the fault of Brexit, because it can be the fault of coronavirus.

This approach shouldn’t work, especially as the government is responsible to an extent for coronavirus as well, given it has managed the response to it – but it is trotted out time and again whenever a minister is asked to account for the various difficulties facing the UK at the moment.

Reality, alas, is not so easy to smooth over. Just as we might not know how quickly we can run a mile, we can be certain we would run it less quickly if made to carry a sandbag the whole way, we can know Brexit is an extra obstacle at a time we need to be unencumbered.

And the worst bit is that we haven’t yet felt the whole crunch of Brexit – and some of the problems it has already caused have got somewhat lost among the Covid chaos.

So here, then, is a summary of some of the Brexit problems we’re facing: a few obvious, some swept under the rug, and a couple you may not have heard of at all…

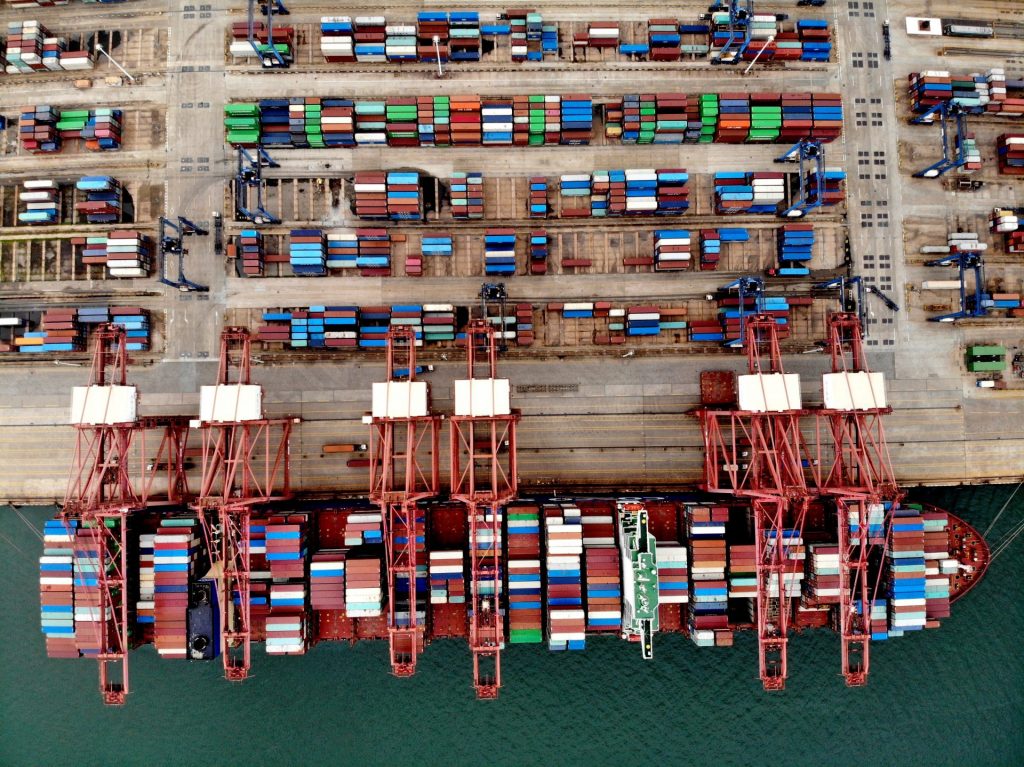

It is fair to say that there are global problems with shipping and supply that go far beyond Brexit – the disruption of a global pandemic will take months if not years to unravel. One of the big problems is shipping.

Not only are shipping containers largely sitting in the wrong places, thanks to months of unusual economic activity, but ports across the world are struggling for staff, often because they are either sick or isolating – meaning that even when a ship could in theory stock up on empty containers and move them to where needed, they have to leave before they can be loaded.

That’s the problem facing the entire world. For the UK, we are trying to manage that alongside a wholly separate and quite visible border problem – a whole series of new checks and bureaucracy introduced as a result of Brexit, as well as further logistical challenges with moving goods around the country by lorry (of which more anon).

We were barely prepared to handle the initial, global, problem alone, and so managing that, along with the self-inflicted ones, has left visible signs of shortages – shelves are already empty, and there are anecdotal reports that the stock that is there has a shorter shelf life than usual.

The problem is worse than most of us realise, though. The latest data from the Confederation of British Industry show that right across the economy retailers have the lowest level of stock since it began collecting data, back in 1983. And we’re not talking marginal differences either: the figures are more than 15 points lower than they have ever been. Expect disappointments at Christmas.

Whatever supply chain miseries await England, Scotland and Wales in the coming months, Northern Ireland is set to fare worse. Already struggling with greater supply difficulties than the rest of the UK, Northern Ireland – where tensions over the Protocol have already led to disturbances on the streets – is set for further disruption as additional GB/NI checks are introduced.

Grace periods on new checks were due to expire from October, but the UK and EU have agreed a last-minute extension – but they will end at some point, and the constant uncertainty as to when isn’t helping either.

Supermarkets are warning of empty shelves, and Marks & Spencer has already cancelled Christmas: Northern Irish shoppers will not be able to make a Christmas order with the retailer, as it simply doesn’t know if it will be able to deliver.

It is seemingly impossible to turn on the television without seeing a news report about the shortage of HGV drivers in the UK right now, and the difficulties that is causing – especially for the broader supply problems already discussed.

The idea of the hard Brexit that the Johnson government pushed through parliament was that it would let the UK diverge from EU rules and ‘forge its own destiny’.

Many of us feared that meant cutting workers’ rights, safety and product standards, or food and animal welfare standards – and those fears remain. Yet, there are undeniably areas where divergence could, potentially, provide a benefit.

One example is in the application of new gene-editing technique known as CRISPR, which unlike genetic modification (GM) before it doesn’t involve splicing together genes from different species, but rather making tiny ‘edits’ of a sort that could appear in nature.

One such CRISPR modification allows us to tweak the wheat used to make bread that could reduce our intake of a chemical linked to cancer which is produced when bread is toasted.

The EU is hyper-cautious on anything resembling GM, and so has classed CRISPR modifications as GM, making them all but unsellable in the bloc.

It might be good for the UK to be able to use this technology in its foods, then – but if it does so, it risks consequences.

An example of this can be seen in the UK trying to diverge on what seems like the pettiest of issues: when the government suggested it might try to change various data protection rules slightly in a bid to curb the endless barrage of pop-up consent windows that appear when you browse the web.

That’s a change most of us would welcome – but the EU swiftly said it would assess any changes to see if the UK legislation was still functionally identical to the EU’s (as is their right).

If not, the EU can revoke the agreement that the systems are functionally the same, creating a huge headache for the UK’s successful tech sector – and maybe even persuading some to leave these shores.

It is a clear sign, if one were needed, of just what Brexit means. There is a risk we have won the freedom to diverge from EU rules, provided we never actually try to do it.

As if having to declare Kent a special secure zone for HGVs and turn half a motorway into a lorry park wasn’t enough, the UK borders have more trouble in store as further checks come into force at the start of next month.

Readers of this newspaper, like other avid Brexit-watchers, will be aware that our border hassles are about to become greater – but the changes could still catch many people off-guard.

The changes affect animal products coming into the UK – exporters have been affected since January, as the EU did not reciprocate the UK’s unilateral delay of checks.

Products won’t be physically checked (as the infrastructure for the UK to do so is, predictably, still not ready), but EU importers will need to show paperwork – which has proven hugely disruptive the other way.

The Food and Drink Federation, who represent UK manufacturers, say the sector has lost £2 billion in exports since Brexit.

The UK is trying to manage an unprecedentedly vast change of legal status for foreigners living in Britain at the same time as turning the screws on an ever-more suspicious and mean-spirited hostile environment system. The two cannot continue to run in tandem without causing major headaches.

The deadline for applying for ‘settled status’ has now passed, and more than five million people did so. Those who did not apply for whatever reason – and we have no way of knowing how many people this is, given we were caught off-guard by the number of applicants – will soon find themselves running foul of authorities.

Landlords are now required to check the immigration status of new tenants, and being an EU citizen is no longer enough to qualify – which could soon catch people out.

Similarly, the NHS is required to charge any EU citizens for healthcare provision, if they did not apply for settled status.

There is a further problem brewing for the future in the millions of people with ‘pre-settled status’, who will need to apply at the right moment in the next five years (which will vary for each) for settled status.

If people – many of whom don’t have English as a first language – don’t understand the difference in the two statuses, they could find themselves losing their right to remain in the UK. Those warning of the potential for a new Windrush are not wrong to worry.

There is a huge array of issues relating to Brexit, large and small, that can’t fit into any neat category. European expats living in the UK complain of the difficulties of sending presents home – they pay for two-day delivery and a parcel arrives six weeks later with a hefty customs charge.

Musicians are facing nightmarish barriers trying to organise European gigs – a huge blow to one of the UK’s strongest cultural exports.

The UK and EU have not agreed a clear system over mutual recognition of judgements from each others’ courts, risking the UK’s future as a major centre for international law. Elsewhere, scientists working with overseas colleagues on a variety of projects are complaining that the delays at the border are leading to delicate samples or specimens defrosting and being rendered useless.

On top of all of that, the Withdrawal Agreement includes a five-year renegotiation of how the deal is being implemented – which will surely be used by both sides to try to tilt things in their favour, creating a whole new wave of uncertainty in the future.

Brexit might not be the only problem we’re facing – but it’s hard to think of a single one it is helping with, and hard to keep up with the number it is hindering.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37