Stolen narratives were the theme when the London Film Festival opened its 65th edition on the South Bank last week.

The big opening night gala at the Royal Festival Hall was a full-on Netflix-powered star-wattage affair, with Jay-Z, Beyonce and Idris Elba at the world premiere of black western The Harder They Fall. I liked the event and the energy more than I liked the film, but its very existence gives voice to characters whose stories have rarely been told on screen, whose black histories have been stolen by Hollywood.

At the same time, five minutes’ walk away at BFI Southbank, another film with a stolen narrative was world premiering – or, to be more precise, re-premiering after 90 years. This was Europa, a remarkable work of the European avant-garde, made in a Warsaw flat in 1931 by Stefan and Franciszka Themerson and looted by the Nazis from a Paris film lab in 1940.

It was believed lost, presumed destroyed, and the Themersons moved to London after surviving the war thinking they would never see their film again. Having nevertheless led a prolific creative life as illustrators and writers, the couple died here in 1988. But in 2019, the artists’ niece and heir, Jasia Reichardt was contacted by Poland’s Pilecki Institute suggesting that copy of Europa had possibly been discovered in Berlin’s Bundesarchiv.

The LFF event told the amazing story of its journey from Paris to the Reich Film Archive, into the East German State Film Archive and then, after German reunification, into the German Federal Archives in 1990. The story continued through the negotiation of its restitution to the Themerson estate, its restoration and digitisation via the BFI National Archive to its premiere with a newly composed soundtrack on the first night of the festival. Europa thus becomes the first-ever film to have been reclaimed from Nazi looting.

Anne Webber is the co-chair of the Commission for Looted Art in Europe and was central to Reichardt getting her aunt and uncle’s nearmythical film back. “Over the years, we have facilitated the return of books, paintings, manuscripts, porcelain, silver, furniture,” she told me. “But this is the first time we have been asked to get back a film. To see it on the big screen, with an audience, after all this time was a glorious moment.”

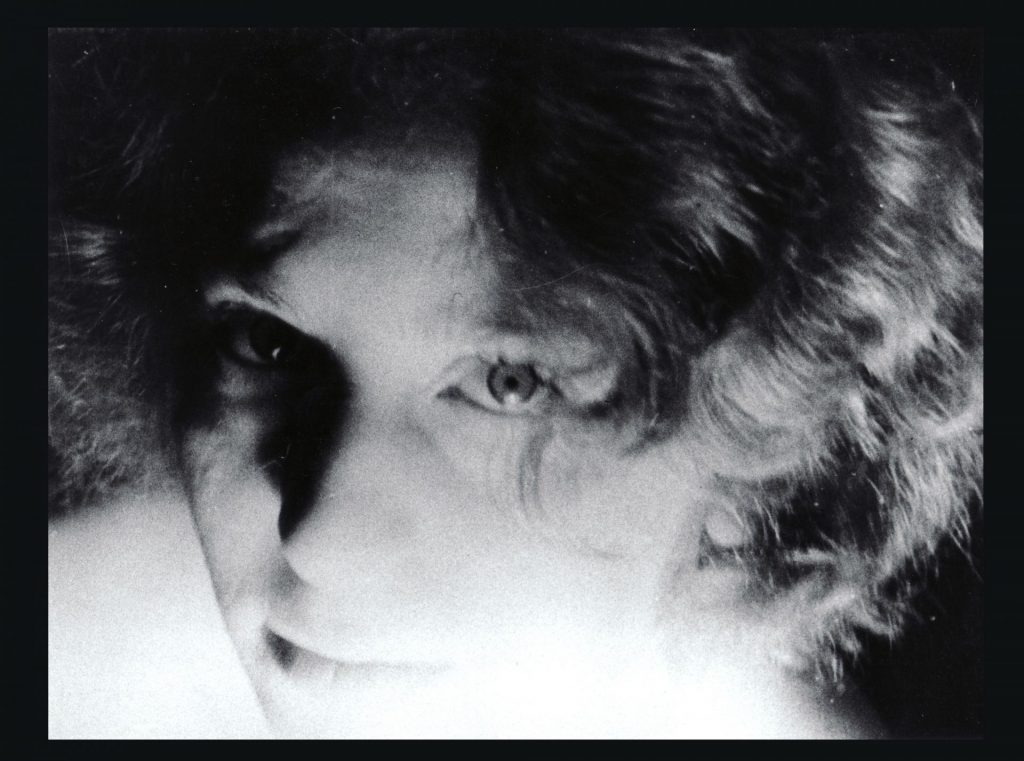

Despite its long and eventful history, Europa is only short, running to just under 12 minutes, yet it packs in a vast and powerful amalgamation of detail, so much so that I felt compelled to watch it again, as soon as it had finished. Adapting a poem by Anatol Stern, the Themersons assembled and shot hundreds of images, overlaying them using pioneering DIY techniques. Close aesthetic comparisons and influences would be better-known contemporary works such as Luis Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou or Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera.

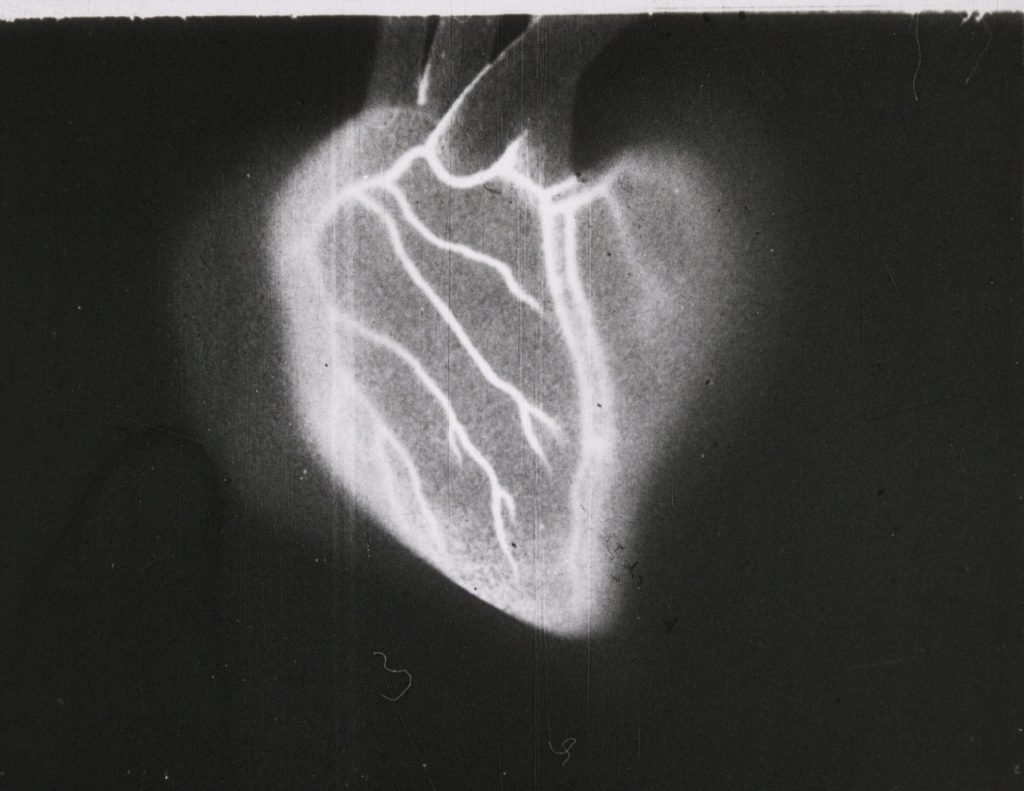

In Europa, layers of meaning accumulate – a fat man eats a stew, another chomps a cigar, newspapers are stuffed into another’s mouth, while an animation of a beating heart pulses, floating over images of dancing girls and neon lights drifting into industrial crowds and typewriters and railway tracks.

A woman peels and slices apples, fading into a swinging pendulum or the back of a wooden lute, into shots of a crucifixion and men in the trenches and barbed wire. Then a boxer, then a fish, then a pipe before naked women run, leaves fall, weeds grow and, shot from above, a diver springs from a high board.

Commonly read as an anti-fascist statement, it feels like it is has as much relevance today, reflecting on the alienating influence of industry and modernity, the saturation of media information, the bloated excesses of capitalism, a yearning for connection.

Preserving and reviving this significant work was a task relished by Will Fowler, a curator at the BFI National Archive. He described receiving the film earlier this year as “a tantalising moment.”

“Nitrate film has to be handled with such care,” he says. “Only a few specialised firms can do it, it’s flammable and precious and opening the can when it arrives it like receiving treasure. Europa had a spectacular look when we got it and, considering the biography and the backstory of the object, it’s remarkably undecayed.”

This is the first-ever film the BFI have received that has been in Nazi hands and, as such, it represents a landmark. “It’s gone from Poland, to Paris, through Nazi capture, to East Germany, then to the Bundesarchiv and now it’s finally here with us, in our Master Film Store. You could say it has now found a home and a place to rest in peace.”

Europa will now rest in its cannister, at -5 degrees and 33% humidity. But a film’s real power can only be unleashed when it is screened. I wonder, then, how this crown jewel of the European avantgarde rates as a ‘lost film’ in terms of the importance of its discovery and where it takes its place in the BFI collection. “As an object, it’s story is remarkable, but as a film, it’s a strident piece, still avant-garde after 100 years, still radical in style and punchy with provocative imagery,” says Fowler. “It’s a real find and the concentration of creative energy that’s gone into every frame is incredible.

“Hopefully it can now live on for centuries and go on provoking a reaction. There’s a genuinely unique, latent power in this one.”

The power is enhanced by a new soundtrack on which one can even hear mashed-up snippets of a notorious campaign speech by current Polish president Andrzej Duda. The new soundtrack was commissioned and composed by Dutch musicologist Lodewijk Muns, and features the theremin, invented in 1928 and therefore at the cutting edge of contemporary sounds that might have been available to the Themersons at the time.

Europa will now receive wider distribution, alongside four other surviving Themerson films. Benjamin Cook, whose LUX label will take the film around the world, said: “This is truly one of the most important film rediscoveries of recent years, a major lost work of the European avant-garde and an affirmation of the Themersons’ contribution to cinema history.”

I wonder if there are there many more stolen filmic masterpieces stored away in national archives? Anne Webber doesn’t know for certain, but believes the story of Europa could well open several more cans of nitrate worms. “There is a huge reluctance to return looted art,” she says. “But it has a value way beyond its mere meaning and although this the first time we’ve seen it in the cinema space, the principle is the same – if you take away someone’s art, you steal their taste, their life work, their creativity.

“In this case, there’s a sense of an audience now getting to see the work of the Themersons. They worked in other disciplines but now this act of restituting and restoring their film is, in a way, to restore them to the artistic pantheon, a status the Nazis stole from them.”

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37