I’ve always been a football supporter. I have seen some big games, great games, matches I will remember for the rest of my life. But there is one very different game that I will never forget. It was a match I helped to organise in the Olympic Stadium in Kabul in the summer of 2002.

The result was England 1-0 Scotland, but none of the players was English or Scottish. They were all Afghans. One team wore England strips provided by the FA. The other team wore Scotland away strips provided by the SFA.

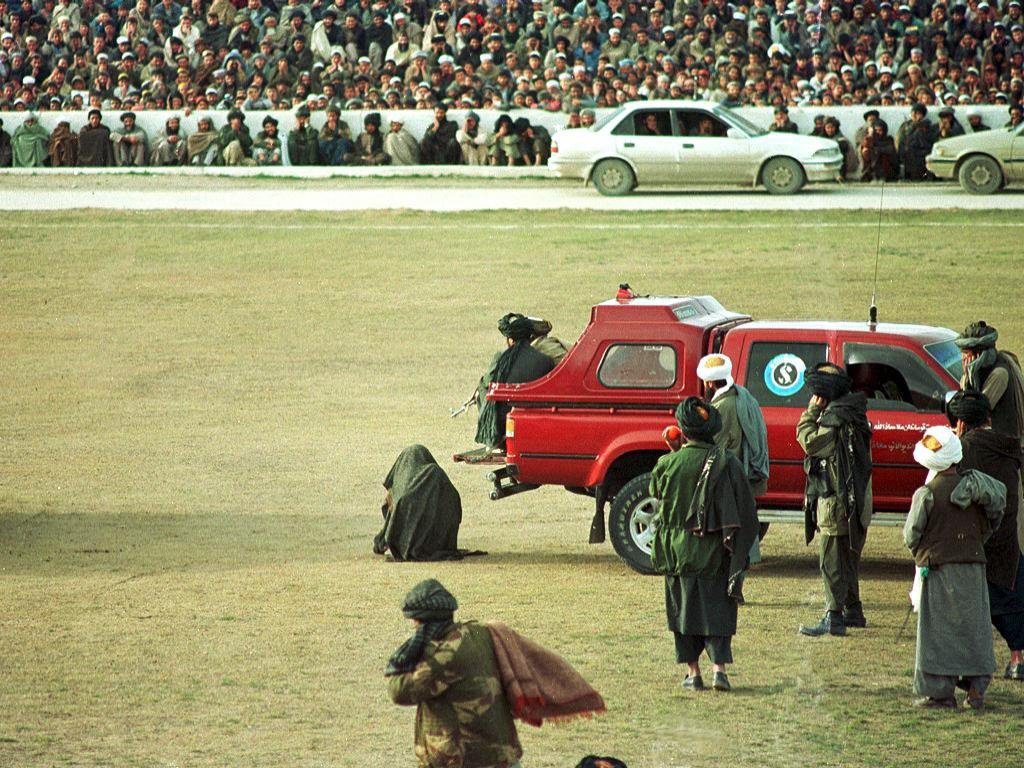

What made the game so special was not the scoreline but the fact that it was taking place at all. Because the stadium in which it was played had become known the world over not for football matches, but as the venue for Friday public executions carried out by the Taliban regime which had ruled the country from 1996 to 2001.

Football has the capacity to move, to thrill, to unite. But that day it brought home its power to be a symbol of change.

Before the match in Kabul, my American colleagues were nervous about security – what would happen if thousands of people came to the stadium?

How could we be sure they were safe. The truth was I couldn’t be sure. I couldn’t guarantee anything. But we advertised the game on local radio and went ahead.

The night itself was a fantastic occasion. On a beautiful summer evening, the terraces which had borne witness to brutal executions were full of fans there to watch what a sporting stadium should be used for. Kick-off was delayed for 15 minutes because one team had been at a wedding, but soon we were underway. At half-time, the crowd rolled out their prayer mats and said their prayers.

Team Kabul wore the England shirts and their opponents, Young Generation, wore the Scotland colours. In a tight game, the winning goal was scored by Najeeb of Team Kabul/England.

I was in the country as part of a joint UK/US team to visit aid projects funded by the two governments, many of which would not have been possible under the Taliban. We visited a bakery where women were allowed to work and a new newspaper able to report freely, both unthinkable under the Taliban. Already girls were being allowed to go to school which had been banned by the previous regime.

At the Pul I Charki refugee processing centre outside Kabul we were told by UN officials that they were witnessing the biggest movement of refugees back into a country in living memory. You can tell something about a country depending on whether people are trying to get into it or out of it.

I asked people why they were coming back. “Because there is hope for my country,” they said. And that football match was a small expression of hope, for those who played and for the thousands who watched, many with their own memories of seeing people killed on the very field where now they could watch two teams kick a ball about.

What a contrast with the desperate scenes we witnessed in recent days as Afghans clung to the undercarriage of a US transport plane seeking any way possible to flee from the return of the Taliban, including tragically, a young Afghan footballer, Zaki Anwari.

The game was only a tiny example of new-found freedom. There were many far more important ones over the years. Millions of girls were allowed to go to school. Women were allowed to work. Elections were held and the Afghan parliament had a diversity of representation which would have been entirely impossible under the previous regime. All this was only possible through the effort of the armed forces from the USA, the UK, the Netherlands, Australia, Canada and of course the Afghan forces themselves.

The country was not fully at peace. There was corruption and violence – sometimes terrible terrorist attacks with great loss of life. Four hundred and fifty-seven members of the UK armed forces lost their lives and many more from other countries. Over the years the allied effort reduced in size and became much more of a support function.

Allied casualties dropped markedly and a stalemate emerged which allowed millions of Afghans much greater freedoms. If nothing had been gained by those efforts, there would be nothing to be lost today. We wouldn’t be concerned about the loss of education for girls, about women judges and journalists being forced out of their jobs or about the brutal intimidation of the population. What we fear may be under threat is only there because of the progress that was made.

We have to judge what comes next by actions, not words. The Taliban claim they have changed. Time will tell. Let us hope the changes made over 20 years will not now be lost.

Pat McFadden is the MP for Wolverhampton South East

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37