Tall and tanned, with scarcely a single silver hair out of place, Michel Barnier is the latest candidate to throw his hat into an increasingly crowded French presidential race.

Once denounced by Eurosceptics in the UK as “the most dangerous man in Europe”, Barnier, 70, is gambling that his technocratic CV – he has served as the EU’s chief Brexit negotiator, a two-time EU Commissioner and four-time French Cabinet minister – will swing voters round to his centre-right candidacy in next year’s election.

Last week, sounding like Joe Biden in the 2020 US presidential campaign, Barnier cast himself as the candidate to heal a fractured nation. “My country is not doing well,” he told the Financial Times.

“It is too divided and fractured – between urban and rural areas, between immigrants and non-immigrants, between the young and the less young.”

Barnier tempered his call for unity with a barefaced pitch to voters flirting with the far-right candidacy of Marine Le Pen: a three-to-five-year moratorium on immigration, putting on hold all requests for residency apart from asylum seekers and students.

His other main policies are a less carbon-intensive economy, a return to hard work and “merit”, and more respect for France on the world stage.

Like so many hopefuls, Barnier’s candidacy is testimony to the allure of the office of president of the Fifth Republic, first held by his political idol Charles de Gaulle. But unlike the imperious de Gaulle, Barnier is light on charisma, a somewhat prim figure with a professorial manner who hails from the Alpine mountains of Savoy.

“You can take the man out of the mountains,” wrote Dave Keating in the Berlin Policy Journal, “but you can’t take the mountains out of the man.”

Jean-Pierre Raffarin, the former French prime minister and a long-time ally, is more generous: “He’s no poet. He’s not a gambler, a player or an acrobat. But he is solid and reliable”.

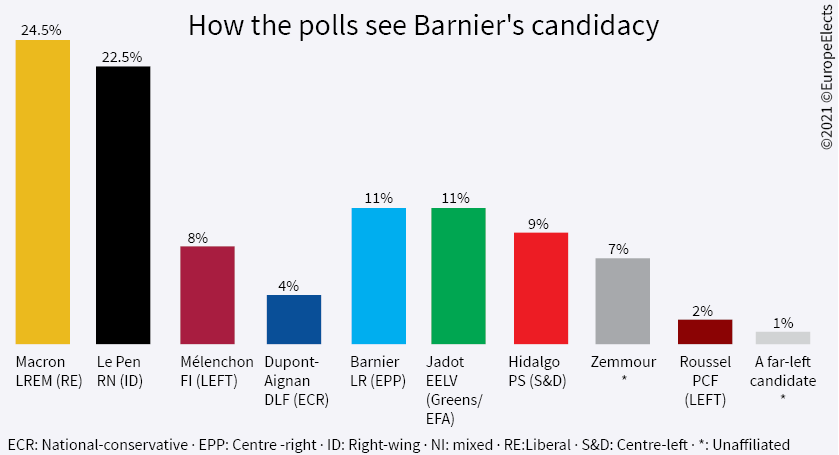

At present, Barnier remains a long shot. He lags behind two other strong candidates in the Republican centre-right party: Xavier Bertrand, head of the Hauts-de-France region, and Valérie Pécresse, head of the Paris region. His other weakness is that he belongs to a deeply divided party trounced by Emmanuel Macron’s En Marche! in the presidential election in 2017.

Bertrand, a former insurance salesman running slightly ahead of rivals in the polls, is resisting calls for a primary election contest to winnow out a lead party candidate for next year’s election. Unless this happens, the Republicans risk splitting the vote, thus guaranteeing a second-round run-off between Macron and Le Pen next April.

Barnier’s signature theme is competence. His office is packed with photographs and memorabilia referring to his role in organising the 1992 Winter Olympics in Albertville – his breakthrough moment in French politics.

As the most distinguished French politician to have served in Brussels since Jacques Delors, Barnier led the Brexit negotiations over four years in which he managed to contract Covid and have two new grandchildren. He emerged with his reputation enhanced as an effective negotiator, albeit at the price of flexibility (especially on Northern Ireland).

Barnier knows all the nooks and crannies of the EU’s internal market.

Between 2009-14, as single market commissioner, he helped to rewrite the rulebook on banks, insurance and markets after the global financial crisis.

During this period, he clashed regularly with the Cameron coalition government and the City of London which pressed for special defence clauses against further economic integration – a proposal vehemently rejected by Barnier who objected to “cherry-picking”, a warning repeated to deaf ears in the Brexit talks.

The million euro question is whether Barnier’s Brussels experience will translate into votes in the first round of voting next spring. (Delors toyed with running for French president but backed out in the end, realising perhaps that his stature abroad was higher than at home).

As Monsieur Brexit, Barnier has yet to reveal how he intends to break the stalemate within his party over how to unite around a single candidate – a matter to be discussed at a party congress later this month. Certainly, there are few clues in his Brexit memoir, La Grande Illusion, published ahead of his presidential campaign.

This worthy tome promises but fails to reveal any secrets other than his disdain for the “baroque” Boris Johnson and his description of Brexit as a “tragi-comedy”. The title is more telling: a reference to the eponymous 1937 Jean Renoir movie which features a group of French prisoners of war plotting an escape during the First World War.

The movie – widely acclaimed as a masterpiece – is based in turn on the 1909 book by Norman Angell which argues that war is futile because of the common economic interests of all European nations. Such high mindedness is very much in the character of Barnier.

How ironic, therefore, if his own candidacy for the top job in France turned out to be a grand illusion too.

BARNIER IN QUOTES

“I don’t even want to smile but there is definitely something that is deranged in the British system.” On hearing then Brexit-secretary Dominic Raab’s surprise that UK trade was “particularly dependent upon the Dover-Calais crossing”

“A courageous and tenacious woman surrounded by many men who put their personal ambitions ahead of their country” On Theresa May.

“Listen to expressions of popular sentiment … and respond to them [with] respect and political courage.” On what lessons the EU must learn from Brexit

“No one has managed to show me what is the added value of Brexit, even Mr Farage.” On Nigel Farage

“Everybody will have to pay a price – EU and UK – because there is no added value to Brexit. Brexit is a negative negotiation. It is a lose-lose game for everybody.” On Brexit

“I can’t work out what’s stopped the UK up to now from being ‘Global Britain’ except its own lack of competitiveness. Germany is ‘Global Germany’ while being solidly inside the EU and the eurozone.” On ‘Global Britain’

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37