Every chap about town should have a pair; evening shoes made from a hand grenade. Or perhaps for the ladies; a beach bag somehow contrived out of a war time commando waterproof.

Just two somewhat boggling innovations from an exhibition Britain Can Make It, held 75 years ago this autumn, which aimed to prove that having won the war Britain had the skills to win the peace by staging an ambitious display of the most compelling examples of homegrown design and invention.

It was launched with more than a dash of post-war jingoism. Movietone news hailed its opening at the Victoria and Albert Museum as a celebration of “new homes in a new world” and to stirring music, the commentator reminded viewers that after the years of rallying to the slogan “Britain Can Take It”, the exhibition was, as King George VI announced at the opening: “Proof of our power of recovery over all difficulties.”

Though ‘Britain Can Make It’ is a slogan snappy enough to satisfy Gove, Cummings, Johnson and Co, with their vacuous renderings of ‘build back better’, ‘levelling up,’ and ‘taking back control,’ none of this strutting attitude was evident in the monarch’s somewhat ponderous delivery nor indeed in the expression of prime minister Clement Attlee who looked on po-faced.

No doubt he was too preoccupied with actually changing society than merely talking about it.

Though later overshadowed by Festival of Britain in 1951 – “A Tonic To The Nation” – the 1946 exhibition caught the mood of a weary nation emerging from their own extreme version of lockdown. It was hugely popular with 1,432,369 visitors over 14 weeks, the men in double-breasted de-mob suits, the women in pearls and frocks, queueing around the block to discover what the future held.

They were thrilled to discover a cornucopia of luxury such as pottery, glassware and hardware, delighted at new brands of cutlery, jewellery, fashion and fabrics, suits and boots. One of the most popular sections highlighted the new, sophisticated living areas to suit people from a range of occupations, incomes, ages and families.

Well equipped kitchens, stylish bathrooms, a “brighter and better” lounge complete with a sun room for families, the room for a sports reporter with a phone by the bed and one described as the “well planned” living quarters suitable for a miner. An early, if patronising, example of levelling up.

A revelatory section, “From War to Peace”, demonstrated how wartime production had been harnessed for peaceful purposes, hence the evening shoes and the waterproof beach bag.

Other examples included an ammunition box from a Hurricane fighter plane which was used to make a pram, a tank periscope reimagined as a glass bowl and an airman’s goggles repurposed as gold and black coasters. Swords turned into ploughshares…

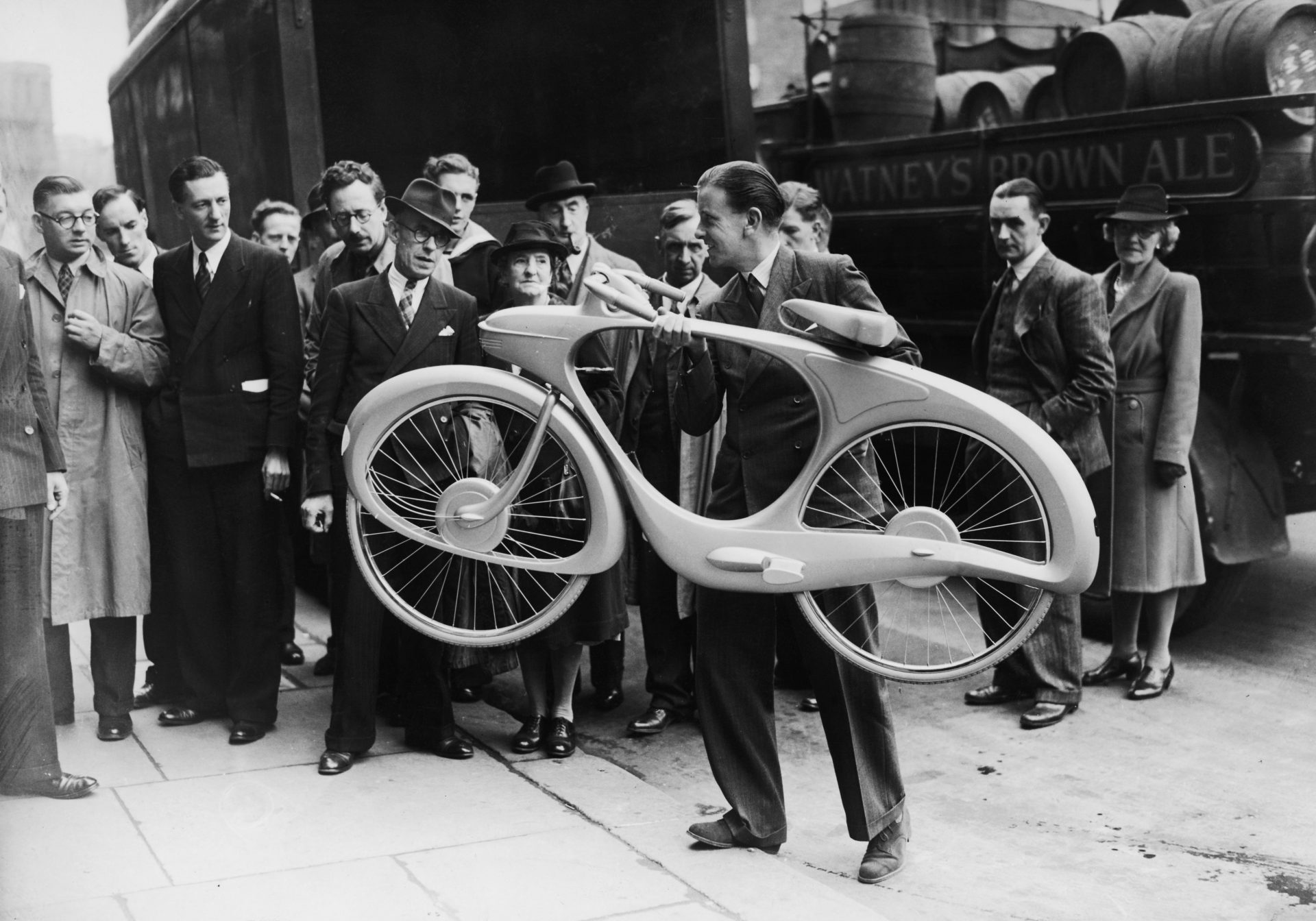

But what caught the eye were the visions of the future; a bike, all swirling curves, with an electric engine and a radio, an air conditioned bed, a sort of frame around a divan which will “get you cosy or cool at the touch of a switch”.

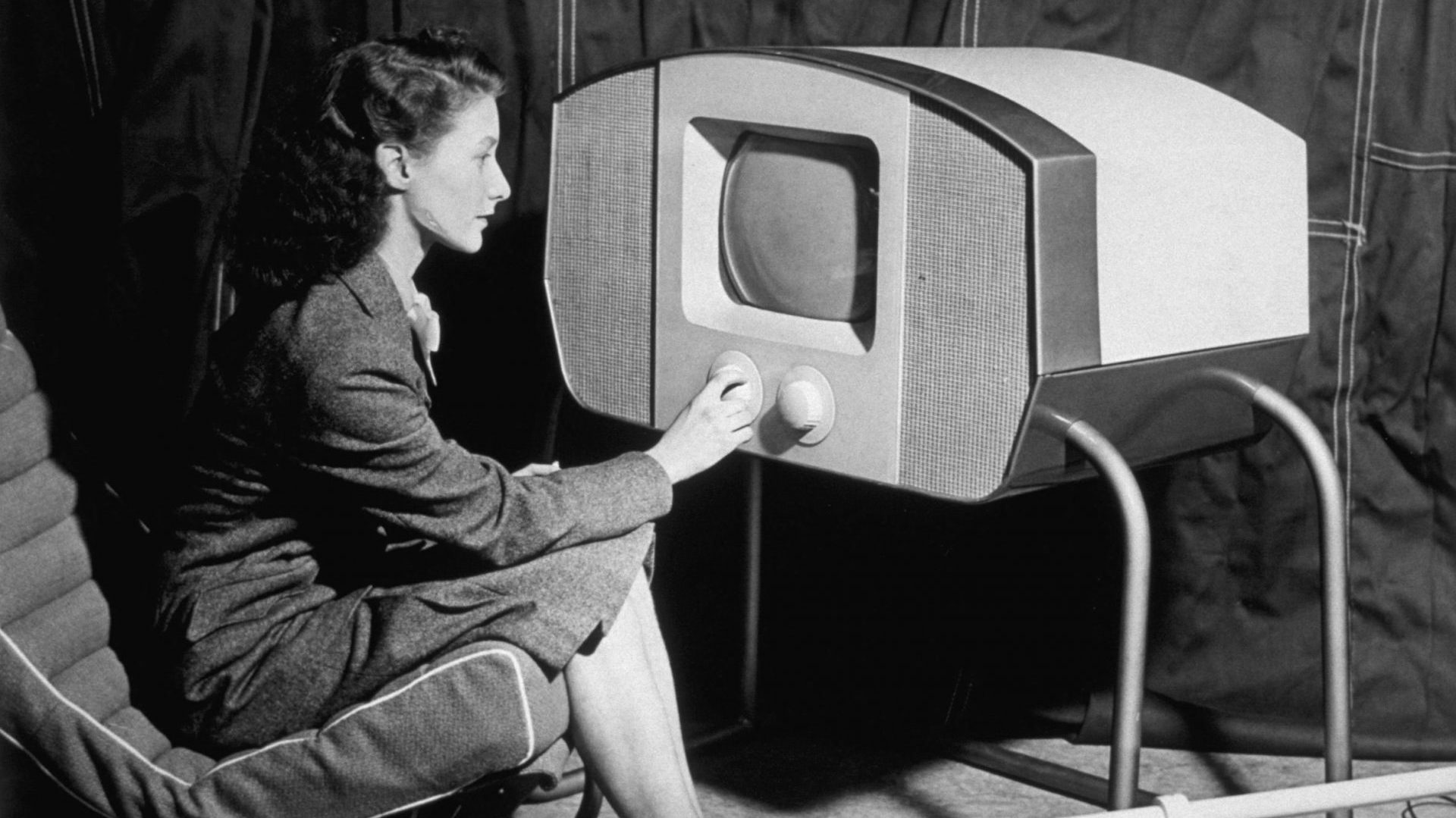

That new fangled TV thing – an astonishing 20 inches by 16 – was housed in a tasteful cabinet so it did not clash with the room’s furniture. It was forecast the device “will be as common a form of domestic entertainment as radio is now”.

For a public who had been trapped in their own country for six hard years, a plastic moulded travel case must have been an attraction, though a space ship which “will rise in a leisurely manner through the atmospheric layers” might have seemed an extreme form of escapism. “A trifle nebulous,” opined the commentator.

I cannot help thinking that an ambitious plan for a third class railway sleeper train would have been more useful than HS2.

Penny Sparke who edited Did Britain Make It? British Design in Context 1946-86 says: “The exhibition was important because, although a lot of the objects existed pre-war and only a handful were new, it was symbolic.

“This is Britain showing itself off to the rest of the world.

“All the great and good of the design world contributed to the exhibition and in terms of design aesthetic I think it was forward looking, picking up on some of the progressive thinking of the 1930s but with some new, industrially designed objects. It showed people what to buy for their homes.

“The designers had a huge belief in the future and that design would be one of the ways of reaching this better world.”

But it was not all sweetness and light. Another phrase cropped up amid the flurry of publicity which has resonance today – the metropolitan elite.

Many of the manufacturers felt that the London-based organisation behind the exhibition, the Council for Industrial Design (today’s Design Council) was part of a “tastemaking” metropolitan elite who did not fully appreciate the realities of manufacturing in the regions.

They resented the way the CoID rejected about two-thirds of the 15,836 goods submitted by industry for display in the exhibition.

Sparke, also professor of design history at Kingston University, near London, says: “Metropolitan elite? Absolutely it was. The Council believed that if you upped the taste of everybody it would sell more, therefore produce more and that would go into overseas trade.

“Taste was key to developing the market place and they were confident that their taste – middle, upper-middle class taste – was deemed to be the right and only proper one.

“They knew what they thought good design was and if you didn’t you had to be educated.”

About 7,000 overseas buyers visited the exhibition, which generated orders of between £25 and £50 million pounds, a tiny amount compare with 2017 figures which showed that the design sector was responsible for an estimated £3.949bn of Gross Value Added – the worth of the contribution by a company or organisation to the economy.

Nonetheless, Sparke is pessimistic. “My sense is that design as an aesthetic has lost its leadership culturally.

“There is so much fragmentation. Today there is a huge, huge, effort on part of designers to be ethical, sustainable, socially led, politically driven, which is great, but it doesn’t result in things anymore.

“Everything is about going green, working with nature, like putting up buildings with plants growing on the outside. It is as if they are saying, ‘we’re good people and we’re doing good things.’ It’s a little bit bandwagony.”

That certainly seems to be the mission of the V and A’s contribution to the London Design Festival this September which is to include projects which will explore the challenge of climate change with a pavilion constructed from aluminium, which has the world’s lowest carbon footprint, and a couture gown worn by an artist robot.

And the ‘bandwagony’ approach gives us a clue perhaps as to the thinking behind a design festival planned for next year provisionally entitled Festival UK 2022 but known by some as the Festival of Brexit.

Details of the £120m worth project are under wraps but there is talk of it being an exploration of the human mind through architecture, neuroscience, technology, light and sound.

And, of course in this era of Johnsonian flim-flam, it already has a slogan: “Open, Original and Optimistic.”

Will it rival the utopianism of the designers of 1946? How to match the ingenuity behind a brand of saucepans made from the old Spitfire fighter plane? How to measure the post-war glow of pride that must have suffused the visitors knowing that many of them had donated their saucepans back in 1939 – to provide the steel metal for the plane?

Whatever its failings the 1946 show was born out of a fierce creativity and an authentic desire to show that a brighter future lay ahead.

Talk about build back better.

■ London Design Festival runs at the V and A, until September 26

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37