Many musicians flirt with revolution, but few have lived it. Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis, who died last week aged 96 and was best-known for his soundtrack for Zorba the Greek (1964), was one of those few, boasting a history as a partisan fighter and political exile, having been at the centre of events in Greece’s turbulent 20th century history.

“Always I have lived with two sounds, one political, one musical,”, he once said, but his politics and the fame of Zorba obscured an output of staggering breadth, from chart hits to works that spoke to the soul of his nation and tried to grapple with the greatest of human tragedies.

Born on the island of Chios, Theodorakis combined a musical virtuosity with a physical robustness. Greek folk music, rebétika (the song tradition of the urban poor), and the sounds of the Byzantine liturgy fed his musical inspiration, but by his teens, his imposing 6ft 5in frame (friends called him o psilos – ‘the tall one’) meant he was made for action as much as the delicate business of musical creativity.

In the Axis-occupied Athens of 1943, the 18-year-old Theodorakis took up arms with the communist resistance. The following year, with the inception of the Greek Civil War, he was sent to the notorious prison camp on the island of Makronisos, as the government moved against the communists.

He was tortured and lucky to emerge alive. He studied intermittently at the Athens Conservatoire, earning his degree there in 1950, before going to Paris in 1954, where more study and the composition of the ballet Antigone, staged to great success at Covent Garden in 1959, followed.

But just as fame as a serious composer beckoned, Theodorakis scored Michael Powell’s film The Honeymoon (1959), and the title song was later recorded by the Beatles. It was a sign of things to come, as in 1965 the bouzouki-soaked Zorba’s Dance became a chart hit. Coming as Theodorakis was also spearheading the éntekhno sound, which fused high and low culture in its mix of rebétika, Byzantine and western influences (his LP Axion Esti (1964) was a classic of the genre), Zorba’s Dance defined Greek music in the foreign imagination forever.

Based on the sirtaki folk dance, Zorba’s Dance was an unlikely pop hit, but it nonetheless climbed to the UK Top 10 to sit alongside the Beatles’ Help!, the Stones’ Satisfaction, and Dylan’s Like a Rolling Stone, as well as hits by the Kinks, the Byrds, the Walker Brothers and Sonny and Cher. It was typical of Theodorakis that as he became a pop star of sorts he also officially entered politics, becoming an MP for the United Democratic Left in the 1964 Greek elections.

But Greece, and Theodorakis with it, was soon to face more upheaval. When the 1967 military coup came, Theodorakis’ music was banned and he was interned in various prisons and camps before being placed under house arrest. After international pressure was brought to bear to free the tuberculosis-stricken composer, he was sent into exile in Paris in 1970.

But imprisonment had not silenced Theodorakis. He was in detention when his Mauthausen Trilogy, based on the poetry of camp survivor Iakovos Kambanellis, was premiered in London. He scored Costa-Gavras’s Z (1969), which fictionalised the 1963 assassination of Greek politician Grigoris Lambrakis, while under house arrest. His March of the Spirit, a stirring setting of a poem by Athenian lyric poet Angelos Sikelianos, was also written during his imprisonment, and it is difficult to imagine a more galvanising call to overthrow the oppressor: “Today I call to all comrades/ Help us raise the sun over Greece/ Help us raise the sun over the whole world.”

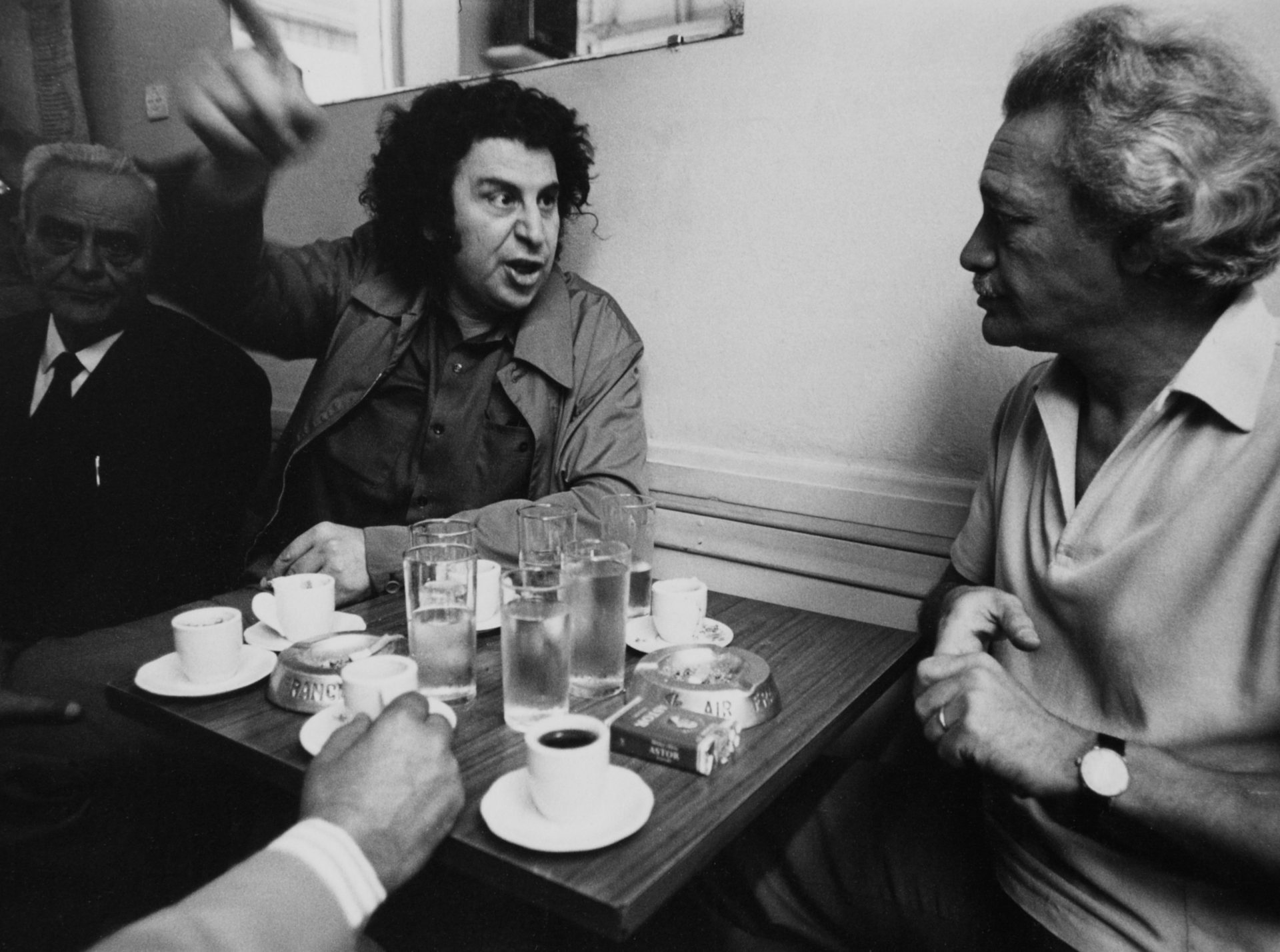

He conducted the London Symphony Orchestra performance of March of the Spirit shortly after leaving Greece, and thereafter stood on the world stage as a symbol of the struggle for freedom, rubbing shoulders with musical and political giants alike as he advocated for the Greek cause.

While a setting for Pablo Neruda’s Canto General were among Theodorakis’ works written during his exile, he again combined the politically conscious with mainstream success. His soundtrack for the Al Pacino police corruption drama Serpico (1973) – its main theme again dominated by bouzouki strings, but the rest bearing the influence of funk and brilliantly evoking the crime-ridden New York setting of the film – earned him a Grammy nomination. Following the fall of the junta, Theodorakis returned to Greece as a national hero, but after being elected to parliament as a Communist Party representative in 1981, he was branded a traitor by leftists when he joined the centre-right New Democracy party and served for two years as a government minister. He continued to compose acclaimed symphonic music, opera and ballet and became music director for state radio and TV in 1993.

For all of his undoubted heroics in Greece’s worst years, latterly Theodorakis’ politics made him a controversial figure as he fell prey to the characteristic follies of the far left. He condemned Nato intervention in the Kosovo War, saying “all that is being said about ethnic cleansing is merely pretext [for American imperialism]”.

In the midst of the Greek financial crisis, Theodorakis decried the Greek government’s diplomatic approaches to Israel, speaking of Zionism’s “control over America and the banking system”. In a letter to centre left newspaper Ta Nea in 2017 he was dismissive of Stalin’s crimes and depicted him as the saviour of Europe.

Well into his eighties, Theodorakis had joined many of his fellow Greeks in demonstrations against a European Union bailout deal that he called a “national betrayal”. He was tear-gassed at one such event – clearly his appetite for action hadn’t waned.

His combination of political passion and artistic inspiration made him representative of his country’s best qualities, and it was not for nothing that, announcing three days of national mourning, Conservative prime minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis called him the ‘Universal Greek’.

Now listen to the playlist:

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37