Even now, 60 years on, the memories are haunting and profoundly shocking.

Mohamed Arezki Ait-Ouazzou, one of those present that day, remembers people falling “like potato sacks” before being picked up and thrown in the river Seine.

Another, Mohammed Ouchik, recalls the sight of others being lined up on Pont Neuilly, then suddenly pushed to their deaths in the water below. For days afterwards bodies were dragged from the water, their arms bound to prevent them saving themselves.

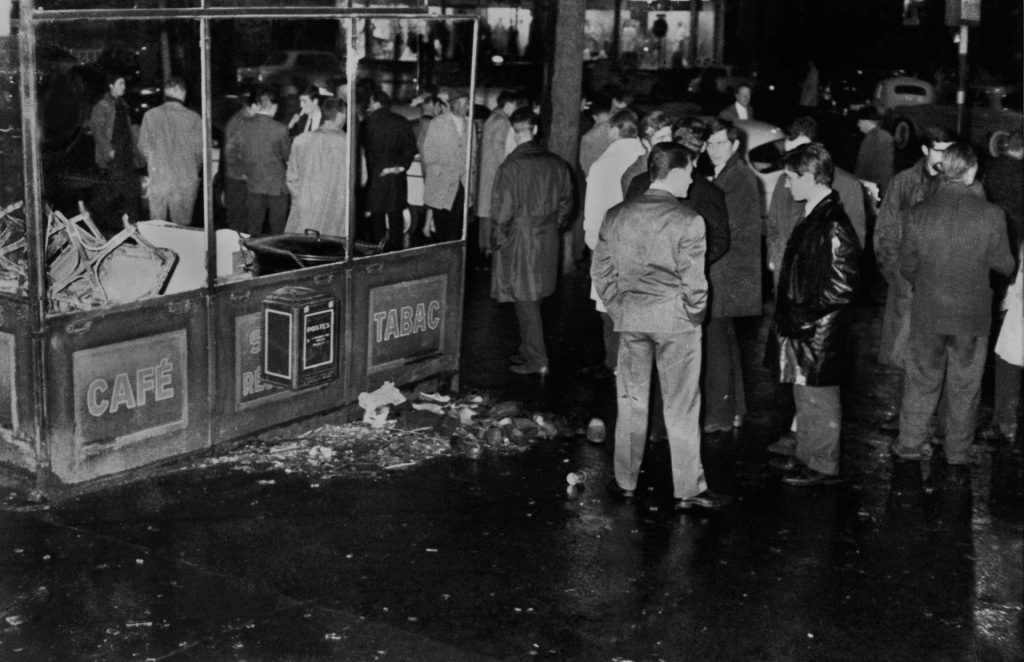

This was the scene on the streets of Paris on the evening of October 17, 1961, the same streets on which Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg had been filming À bout de souffle just two years earlier; at the heart of a city seen as one of the most civilised, sophisticated and dynamic places in the world; home to thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir and others considered at the forefront of a new enlightenment spirit.

The victims were protesters demonstrating against discriminatory measures imposed on French Algerians, against the backdrop of the North African country’s war for independence from France. The perpetrators – those responsible for drowning their fellow citizens; for shooting some and garrotting others; for cracking skulls with rifle buts and pickaxes – were the police officers and security forces of the French Fifth Republic.

The truth about their actions that night were long suppressed and the world at large was ignorant of them for decades. Even now, the story of the massacre is one that France has not fully come to terms with. Even now, there is no clear idea of how many were killed that night.

Such was the cover-up at the time that the authorities would initially say only two, then three, deaths had occurred. After 37 years of denial and censorship of the press, in 1998 – the year France celebrated the World Cup victory of its multicultural football team, with its talismanic French Algerian Zinedine Zidane – the French government finally acknowledged around 40 deaths. There are credible accounts that put the death toll at more than 200, or even as high as 300, with a few hundred more missing.

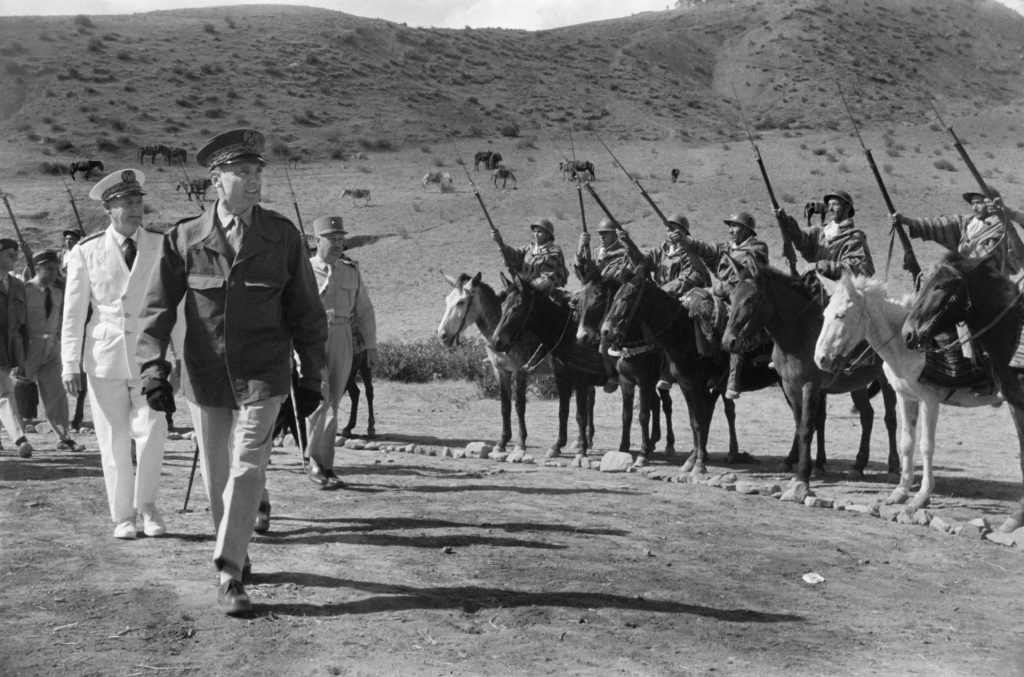

To understand the events of that night, and the collective silence about them that followed, it is important to understand, firstly, one of the issues that defined France throughout the 20th century and beyond – its relationship with Algeria – and secondly, one man: Maurice Papon, who was chief of police at the time.

Algeria had been an integrated part of France since it was colonised in the mid-19th century, so its struggle for independence after the Second World War was akin to a civil war in its brutality and cruelty.

Most of the violence – and the overwhelming amount of deaths – had been in North Africa. But metropolitan France did not escape the bloodshed.

The National Liberation Front (FLN) had taken its campaign across the Mediterranean, with bombings targeting police in Paris and its suburbs.

Meanwhile, the Organisation Armée Secrète (OAS) – a paramilitary group set up to resist Algerian independence – conducted its own campaign in Europe and Africa, with bombings and assassinations (Charles de Gaulle and Sartre were among those it targeted).

Early in 1961, de Gaulle had won a referendum backing his policy of offering self determination to Algeria and he had begun secret peace negotiations with the FLN. The end of the war was looming, but the bloodletting was not yet over.

Despite the high level talks, the FLN resumed bombings against the French police at the end of August 1961. Up to the beginning of October, 11 officers were killed and 17 injured.

In response, raids were carried out on the city’s Algerian population (which numbered some 150,000). Many were arrested and there were foreboding reports of some being thrown into the Seine by police.

At the beginning of October, a nighttime curfew for “Algerian Muslim workers”, “French Muslims” and “French Muslims of Algeria” was introduced. The French Federation of the FLN organised a mass demonstration against it, scheduled to take place on October 17. Police refused permission for it to go ahead, but the organisers proceeded anyway. The stage was set for a day of chaos and carnage. A massive police operation was staged to prevent the protesters gathering, blocking Metro and train stations, but an estimated 30,000-40,000 managed to join the demonstration, many of them women and children.

The FLN had ordered that the demonstration be a peaceful one, insisting that the marchers were to be presentable and unarmed. Ait-Ouazzou, who was among the organisers, was tasked with searching participants to make sure not even a flick-knife was being carried.

There seemed to be less restraint on the part of the police. Raids were carried out across the city and attempts made to break up demonstrations, by blocking routes and rounding people up.

Algerians were taken off trains and lined up and beaten in tunnels before being shoved onto buses bound for detention centres.

Some died on the spot. One young man, who was frogmarched out of Madeleine station to the background sound of shots being fired across the city, recalls being squashed with thousands of others into the Palais de Sports, an indoor arena near the Porte de Versailles. Every 15 minutes more people piled in to be greeted by brutal “welcoming committees” of police.

Several thousands still managed to avoid the police blockade and protest peacefully along the orderly boulevards of Hausmann’s elegant city centre. But when they reached the Opera district, they were cornered by a wall of police. They retreated. The police charged, shooting as the screaming crowd dispersed. Some of those chased to the shores of the river were dumped in the water and not seen again.

Photographs from the time show pictures of besuited, moustachioed men lying on the ground, some possibly dead, with even the sepia tint unable to disguise the streaks of blood on the pavement.

Some eyewitnesses reported seeing bodies piled up as the death toll mounted.

It had become a rout, but the violence was not yet at an end. By now, the police were dispersed on manhunts across the city centre and suburbs, rounding up anyone they could find. Clara Benoit, a Renault worker and Algerian sympathiser who had gone to observe the protest with her husband, Henri, managed to save one wounded person they found staggering into a doorway.

“There were several police cars lined up, and getting out of them were Algerians, arms in the air, being bludgeoned as they walked along,” she said. “I found it disgusting, and still remember how we were shocked because these people had been arrested, without weapons, they weren’t fighting back, they had their hands on their heads for protection, and they were still being pushed to an annex of the police station.”

As the evening wore on, the round-up centres where detained Algerians were sent became more and more crowded. There are reports of torture and multiple indiscriminate killings.

Many were kept in these locations for several weeks, while the torture continued. One recalls spending weeks breathing the musty stench of the hall he was kept in, buying snacks and cigarettes from riot police, preferring to urinate in his pants rather than run the terrifying gauntlet of policemen along the route to the toilets and get beaten as he went past. “They tortured us with hot iron rods to learn the names of our leaders,” he recalled. “At night they woke us with jets of water.” He was eventually deported to Algeria, where he learned his family had already been killed.

The terror did not end that night. Rahim Rezegat, then 17, had stayed away from the protest after hearing about the police brutality, and hidden in a hotel off the main drag. One Friday, there was a big round up and he saw members of the security forces coming towards him. “As soon as they got here,” he remembered, “they killed someone who was performing his ablutions.” Rezeget was taken to a detention centre in Vincennes, where police stood in line, kicking and spitting at the detainees, and hitting them with truncheons.

The raids and violence continued for days after October 17. And so, it seems, did the drownings. Bodies were still being discovered along the banks of the Seine for weeks afterwards.

The stories from October 17 and its aftermath are gruesomely varied, but one constant is Maurice Papon. As head of the Paris police he had not only overseen the violence, but had seen it, up close. He had stood metres away as tens of civilian Algerians were killed in the police headquarters’ courtyard. Officers would then throw bodies into the Seine off the nearby Pont St Michel, muddying, quite literally, the evidence for any future inquest.

His role is central to understanding the events of the day, but also why they remained obscured for so long, and why they continue to haunt France. After all, this was not the first time he had organised a massacre.

As a functionary in the Vichy regime, Papon had helped orchestrate the round-up of 1,600 Jews from the Bordeaux region and sent them off to the Nazis. Yet his collaboration did not impede his career after the end of the Second World War. (He covered his tracks skilfully, becoming involved with the French Resistance as Germany’s defeat became inevitable.) In fact, he did rather well and found himself progressing through a series of public service roles.

In the 1950s, he was sent to Algeria, where the bloodletting was intensifying. Here, he actively supervised methods later used in Paris – prohibited zones, detention centres, torture of civilians and summary executions.

In 1958 he became head of the Paris police and thus played an important role when, a few months later, a political crisis precipitated by the war in Algeria saw the collapse of the Fourth Republic and the return of de Gaulle. The president later gave him the Legion of Honour.

The police force he now led was, in many ways, in his image. He was far from the only former collaborationist in its ranks. Indeed, it is said to have still included many officers who rounded up Jews in Paris for the Nazis in 1942. Two days before Papon’s appointment, 2,000 officers had tried to enter the National Assembly, encouraged by far-right deputy Jean-Marie Le Pen – father of current presidential candidate Marine – chanting “Sales Juifs! A la Seine! Mort aux fellaghas!” (Dirty Jews! Into the Seine (river)! Death to the (Algerian) rebels!).

With their fellow officers being murdered by the FLN, many of those in the force must have felt like they were at war. And Papon certainly encouraged that sense. On October 2, 1961, at the funeral of an officer killed by the FLN, he had said: “For one hit taken we shall give back ten!” Before the month had ended, his officers would do just that. In another speech, on October 2, he had told officers: “You also must be subversive in the war that sets you against others. You will be covered, I give you my word on that.” Again, he was to prove quite true to his word.

According to eyewitnesses and official reports, he choreographed the massacre of October 17 himself. So ‘successful’ was it, that the tactics were repeated four months later, when another pro-Algeria protest – this one organised by left wing groups – was met with ferocious police violence and resulted in nine deaths at the Charonne metro station.

Neither massacre seriously threatened Papon’s position, however. It was not until 1967 that he finally left his post, amid the fallout from the still unsolved disappearance of a Moroccan dissident. Mehdi Ben Barka vanished in Paris in 1965. Theories suggest the French police were involved.

De Gaulle had arranged a soft landing for Papon though. The president helped him to become president of an aviation company which built the first Concorde. Papon also became an MP, for the de Gaulle’s Union of Democrats for the Republic.

By the end of the 1970s, he was a budget minister under president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. It was only in 1981, just days before presidential run-off election between Giscard d’Estaing and François Mitterrand, that Papon’s past started to catch up with him. But it was his wartime activities, rather than the events of October 1961, which first ensnared him.

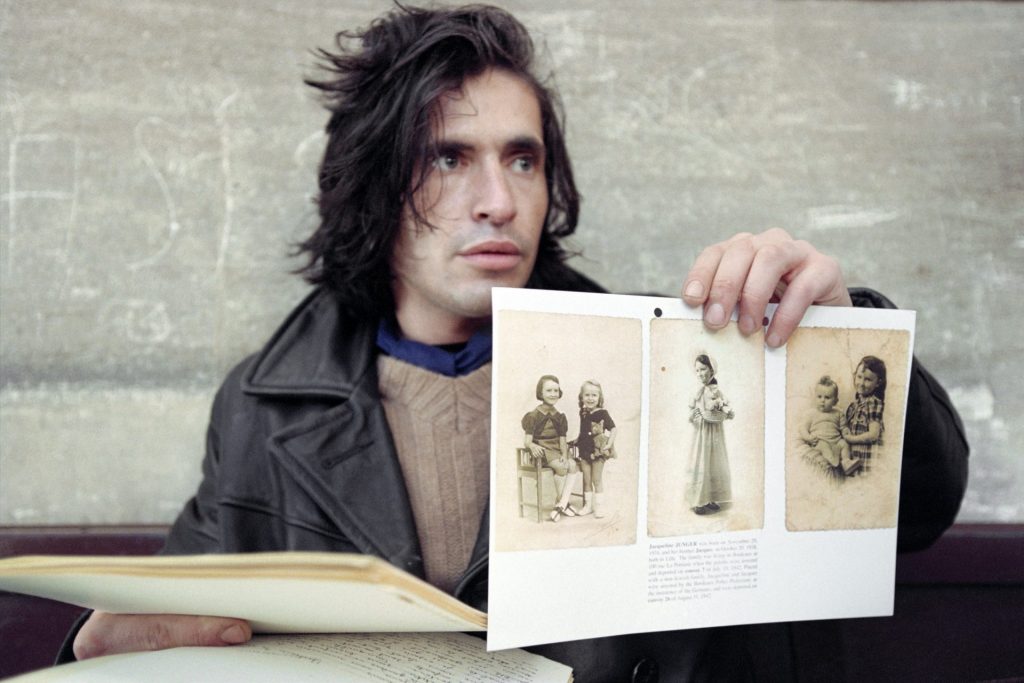

Reports of his involvement in the deportation of Jews surfaced in the press, thanks to the curiosity of a young historian, Michel Bergès. While trawling departmental archives, Bergès had come across evidence regarding the forced deportation of Jews from Bordeaux between 1942 and 1944 to a transit camp near Paris, from where they were sent to death camps. Several were signed by Papon. Bergès showed them to former resistance fighter Michel Slitinsky, whose Jewish family had perished after being deported. He took the documents to the satirical weekly Canard Enchaîné, which agreed to publish.

Papon was officially charged with crimes against humanity in 1983, but due to the slow French judicial system and political reluctance by, among others, François Mitterrand, he wasn’t tried for years.

Finally, in 1998, after the longest trial in post-war France and a traumatic seven months for the French public, he was found guilty. Sentenced to only 10 years on the grounds he couldn’t have known about the death camps at the time, Papon was released after only two and a half due to deteriorating health. He argued he had only ever followed orders and ensured good treatment of those in his custody.

He never expressed remorse for his actions, maintaining he had no choice. He died in 2007. He was buried with his state medal despite political disapproval.

While Papon’s wartime activities are now well established, his role in 1961 has never had the same public airing. Rather, it has been left to investigative reporters and authors to piece together what happened on the streets and courtyards of Paris.

“He was never held to account for the massacre,” colonial historian Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison told me. Lawyers had tried, but got nowhere amid enduring establishment reluctance.

“Yet we’re talking about a crime of humanity,” Grandmaison said. “A premeditated, politically and religiously motivated racist act prepared by a collective, involving torture and orders from above.”

With many senior figures still relics from Vichy France and implicated in brutal practices in Algeria, it wasn’t in anyone’s interests to drag Papon’s history into the light – bad as Papon was, he wasn’t even uniquely so.

Perhaps one reason he was never pursued over 1961 was that the French were never given the full story of what happened. Or, if they were, they were soon encouraged to forget.

Contemporary reports of the massacre minimised the scale and brutality, even though detailed information and witness reports were initially available – this did, after all, take place under everyone’s noses.

Communists spoke out, and soon afterwards, feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir condemned the massacre in her memoirs, pointing the finger at Papon. “Corpses were found hanging in the Bois de Boulogne, and others, disfigured and mutilated, in the Seine,” de Beauvoir wrote. “Ten-thousand Algerians had been herded into the Vél d’Hiv (a velodrome close to the Eiffel Tower), like the Jews… once before.”

Information was allowed to disappear, documents were destroyed or hidden. According to Reporters Sans Frontières, copies of the Algerian newspaper Liberté were confiscated by police. It had contained an article by Algerian journalist Hakim Sadek, entitled When the Seine was full of bodies.

There was pressure and censorship, but also a widespread failure of a media cowed and listless after years of government control, and also maybe wanting de Gaulle’s administration to succeed. Many editors stuck to the government line rather than report the events on their doorsteps.

hotographer Elie Kagan had many pictures of that night, including images of two Algerians sprawled over a small stone wall – one dead — after panicked police had sprayed them with gunfire. He said newspapers refused to publish them saying they were “too shocking”. One editor told him that if he used the pictures he would face repercussions. “They said ‘fantastic pictures, but we will be attacked if we use them’.”

Protesters were shown being arrested and Algerians filmed being deported from France, but nothing was said about piles of corpses or police stranglings. Even the foreign media, perhaps parochially underestimating the horrors or simply preferring the comfort of official figures, made little of the slaughter.

This made it easier for people who had been involved, including Papon, to continue to occupy roles in society. The massacre – or anything much about colonialism – was not taught in schools.

Even Algerian children were in the dark. Algerian and French writers did eventually keep the story alive through reportage and novels, but it was the dogged work of historian and writer Jean-Luc Einaudi, a chronicler of French suppression of Algeria’s independence movement, that finally pushed it front and centre. His 1991 book, La bataille de Paris, meticulously brought the story to life.

Community activists have been trying to reinsert this ‘confiscated memory’ into France’s historical narrative. Some have erected banners by the Seine reading “We drown Algerians here”.

Survivors now attend memorial events. On the 40th anniversary of the killings, the socialist mayor of Paris, Bertrand Delanoë, unveiled a plaque on Pont St Michel, near police headquarters, “In memory of the numerous Algerians killed during the bloody suppression of the peaceful demonstration on 17 October 1961.” The centre and right-wing opposition on Paris City Council boycotted the unveiling ceremony, while police unions protested Delanoë’s decision.

Photo: François DUCASSE/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

It was October 2012 when president François Hollande spoke of “several dozens of deaths under tragic conditions”, his words marking the first proper official acknowledgement. Emmanuel Macron has gone a bit further, and also became the first president to acknowledge systematic torture in Algeria by the French. But neither spoke of repentance.

The relationship between France and Algeria remains strained as a result of the violent events in which they were involved in the middle of the 20th century. The last echoes of October 17, 1961, are still with us.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37