Neither Labour nor the Conservatives will admit it, but both have lost their favourite line of attack against the other. Following the pandemic, and the announcement of a new tax to pay for extra spending on health and social care, the Tories can no longer be plausibly attacked as a right wing, laissez-faire, small government party. Equally, in ejecting Jeremy Corbyn from the parliamentary party, and obliterating all traces of Corbynite Marxism, Keir Starmer has shown that he is no left wing extremist.

To be sure, there will be some on both sides who will continue to fight on an ideological battlefield that wiser combatants have deserted. But the more thoughtful speeches of the conference season have pointed to the terrain on which the next election will be fought. Both parties will seek to persuade voters that they are more competent than the other. When Rachel Reeves, Labour’s shadow chancellor, tells her party’s delegates as the petrol crisis rages that she wants to fight the Tories on economic competence, the point is not that she will win – that is far from certain – but that her ambition is not as ridiculous as it would have been at any other point in the 11 years since Labour lost power. The real chancellor, Rishi Sunak, made his rival claim to competence at the Conservative conference this week: “I’m a pragmatist. I care about what works, not about the purity of any dogma.”

To say all this is not to say something wholly new. Competence has always been a potent electoral factor. In 1979, the Winter of Discontent wrecked Labour’s chances of staying in power. In the 1990s, the Tories never recovered from the humiliation of Black Wednesday – even though decision to devalue the pound ushered in an era of rising prosperity, falling unemployment and low inflation.

In September 2000, Tony Blair’s Labour Party briefly fell behind William Hague’s Conservatives for the only time in the 1997-2001 parliament, because blockades of oil refineries meant that many petrol stations had to close. Eight years later, Labour’s slide towards defeat began with a financial crisis for which the Tories successfully blamed Gordon Brown.

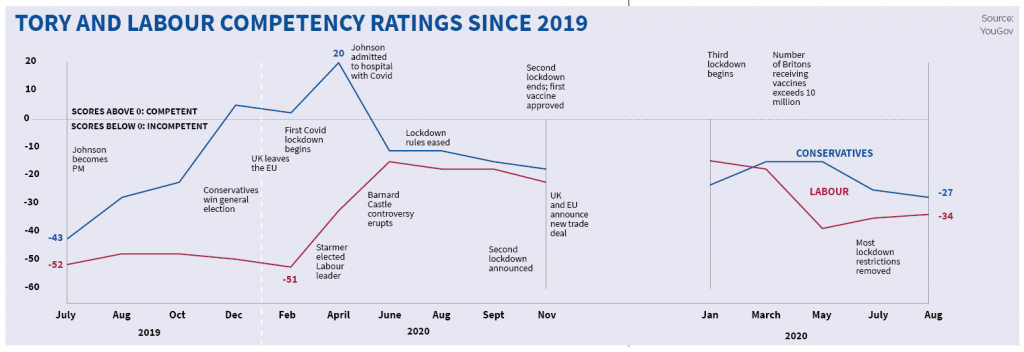

So competence has always mattered. However, with both main parties seeking to don the mantle of centrist prudence, competence now matters more than ever. How, then, do the two main parties stand on this crucial measure? Since mid-2019, YouGov has tracked this issue (see tracker graph).

Every eight weeks it asks whether people think the two main parties are competent or incompetent. The chart tells the story. In the dying days of Theresa May’s premiership, and with Corbyn still Labour’s leader, both parties had truly awful reputations. Just 16% of voters said the Tories were competent, while almost four times as many, 59% said they were incompetent. That produced a net score of minus 43. Labour’s figures were even worse: 12% competent, 64% incompetent: net score, minus 52. Boris Johnson’s arrival boosted the Tories’ competence rating, but it still remained weak until the election that December. The party’s net score went positive, with more people saying it was competent rather than incompetent, peaking in April last year, following Johnson’s time in hospital after catching Covid.

Labour, meanwhile, suffered terrible ratings until Starmer replaced Corbyn as party leader. From the middle of last year until early this year, the two parties enjoyed – perhaps a better word is endured – similar competence ratings. Both were clearly negative, though not horrendously so.

Fluctuations during that period could be explained by the ebb and flow of the news cycle. This was of course dominated by Covid and the on-off lockdowns, with Dominic Cummings’ trip to County Durham adding to the unfolding drama and damaging the Tory brand. Both parties have remained in negative territory this year, though once again Labour has slipped back to dangerously bad ratings while the Tories have mostly remained merely poor.

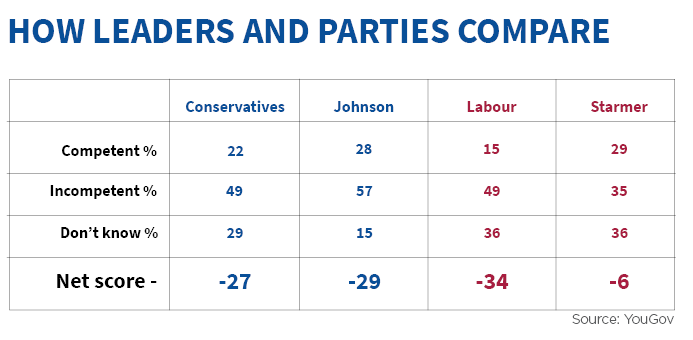

Before we look at lessons for the future, one more piece of polling evidence is worth noting. Normally the reputations of parties and their leaders are much the same – but not always. We are currently living through a period where this is only half true.

YouGov’s latest competence figures for the two main parties, compared with those of their leaders, show that on the Tory side, the net figures are much the same; the only difference is that more people have views about Johnson than his party – both positive and negative. But on the Labour side, Starmer runs miles ahead of his party. In net terms, while the Conservatives do slightly less badly than Labour, but the leader of the opposition is well ahead of the PM.

This is obviously good news for Starmer, but there are three reasons to be cautious. The first is that the numbers of people saying he is positively competent – 29% – is much the same as Johnson’s 28%. The difference is that as many as 57% accuse Johnson of incompetence, compared with just 35% saying the same about Starmer. With both Labour and its leader, more than one-third of voters are undecided. Many of them will come down on one side or the other by the time of the next election; but which way will they jump?

The second reason for caution is that history provides one clear example of what happens when the reputations of a party and its leader diverge. In the Winter of Discontent in 1979, the Conservatives piled up big leads in the opinion polls, while rubbish piled up in the streets. But apart from a few weeks at the start of the year, Gallup found that Labour’s James Callaghan was preferred as PM over Margaret Thatcher, his Tory challenger. In Gallup’s final election poll, 43% thought Callaghan would make the best PM, as against just 30% saying Thatcher. That 13-point lead was no use to Labour. It still lost the election. When campaign push came to voting shove, the standing of the party mattered more than that of its leader. It’s possible that Callaghan’s personal reputation saved Labour from an even heavier defeat, but that was scant comfort for a party that was cast into the wilderness for 18 years.

Third, Starmer does not even have Callaghan’s strong personal appeal. For most of this year, Johnson has led Starmer as Britain’s preferred prime minister, even while lagging him on competence. (Opinium finds that even after Labour’s latest conference, Johnson leads Starmer by a virtually unchanged six points.) In 1979, Callaghan had the benefit of having been a front-line politician for 15 years, and prime minister for three. Voters had developed clear views of him. Starmer’s reputation is less clearly defined. His ratings are softer. He provokes less intense hostility than either Corbyn did before the last election or, indeed, Johnson does today. But too few voters positively want him or his party in government.

These figures suggest that Labour and the Tories face different challenges if they are to win the competence war at the next election. Starmer must do two things: convert a reasonable but soft reputation into a positive and firmly-held belief that he really would be a good PM; and then persuade voters that he has reformed his party and made it as competent as he is. That second task is at least as crucial as the first: Starmer cannot win the next election on his personal reputation alone. And Opinium’s post-conference poll confirms that little has changed on either voting intention or competence ratings in the past month. Johnson’s challenge is different. He and his party share similar ratings: few voters see a difference between them. But as far as competence is concerned, that reputation is bad.

Johnson can take only limited comfort from the fact that the petrol crisis has not made it worse. He needs to take the advice he recently gave Emmanuel Macron: “prenez un grip” and govern more effectively than he has in recent months. With the polls showing only a modest Conservative lead, the competence battle could go either way.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37