The theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre on 22 August, 1911, marked a low point for a museum already notorious for its poor security. Briefly, Pablo Picasso and his friend, the writer Guillaume Apollinaire fell under suspicion and though they were quickly exonerated, they were terrified all the same.

For while it was true that they had played no part in the theft of Leonardo’s masterpiece – later recovered in Italy – they were in possession of two ancient Iberian sculpted heads, stolen from the Louvre some five years previously.

Picasso had first seen the two heads in 1906, in the Louvre’s newly inaugurated Iberian gallery which introduced to the public the material culture of pre-Roman Spain, only recently unearthed at sites across the southeastern part of the peninsula. The statuettes were among a large haul of sculpted stone heads, busts and seated female figures recovered in 1871 from Cerro de los Santos (the Hill of the Saints), the site of a religious sanctuary in Albacete, dating from the 4th century BCE.

Now, the Cerro de los Santos heads are a highlight in an exhibition at the Centro Botín, Santander, which is the first to explore in detail the influence of ancient Iberian art on the work of Picasso. Curated by Cécile Godefroy and Roberto Ontañón Peredo in collaboration with the Musée National PicassoParis, Picasso Ibero includes loans from the Louvre, seen in Spain for the first time, among some 200 works of art from public and private collections.

Together with a plaster copy of the Lady of Elche, discovered in Alcudia in 1897, and a series of sculptures recovered from Osuna, near Seville, in 1903, the Cerro de los Santos treasure was a revelation to Picasso.

The product of sustained contact with successive occupying forces beginning with the Phoenicians and Greeks, and finally the Romans in 219BCE, Iberian art provided Picasso with a model of non-canonical art, that was nevertheless inextricably linked to the origins of western art, and specifically to his own Andalusian roots.

“In the space of two years”, write the exhibition’s curators, “Iberian art led Picasso towards a new form of representation, favouring the passage to primitivism and constituting one of the principal sources of proto-Cubism.”

Warriors and acrobats, birds and bulls, female nudes, and heads described in sparse, but expressive lines are as essential to Picasso’s work as to ancient Iberian sculpture and painting.

Dating from the 6th to the 2nd centuries BCE, the objects in the exhibition include large sculptures of animals and mythical beasts, pottery painted with geometric and narrative designs, and 30 of the 95 small bronze statues that Picasso acquired, probably at some point in the 1930s and 1940s. By comparing these with examples of Picasso’s work, the curators trace a longstanding dialogue, manifested in the artist’s paintings, drawings, sculpture, and ceramics.

To what extent Picasso had been complicit in the theft of the two statuettes in 1907 remains a matter of conjecture, but he referred to the incident some 50 years later in a characteristically off-hand manner, placing the blame squarely with Apollinaire, who had died in 1918. “Do you remember that affair I was mixed up in, when Apollinaire stole some statuettes from the Louvre? They were Iberian statuettes … Well, if you look at the ears of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, you’ll recognise the ears of those sculptures!”

Painted in 1907, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon represents a crucial moment in the modernist project, and its mythical status is today matched only by that of the Mona Lisa. Though not fully cubist, it contains essential elements of this fundamentally new way of seeing developed over the following years by Picasso and Braque. Pictorial space is compressed and flattened, and the angular, fractured figures are seen from multiple viewpoints.

Its subject matter was no less revolutionary, and the confrontational, even aggressive gaze of the women in “mon bordel” (“my brothel”), as Picasso liked to call his painting, is markedly different to the submissive attitude more commonly seen in traditional depictions of female nudes.

The disquieting nature of our encounter with the five women in Les Demoiselles is in large part due to their impersonal, masklike faces. Commentaries on the painting typically focus on the two women to the right, whose faces were modelled on African tribal masks seen at the Musee d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, but even a passing comparison between the two central figures and the Cerro de los Santos statuettes reveals similarities – in their frontal composition, in the shape of the eyes, and even the yellowish colour of the skin – that go some way beyond their ears.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was the culmination of a period of intense productivity rooted in Picasso’s discoveries at the Louvre in the spring of 1906 and nurtured that summer, on a trip to the Catalan village of Gósol in the Pyrenees, accompanied by his lover and model Fernande Olivier. In this remote location, far from the Paris art world, Picasso attuned himself to an unfamiliar, ancient aesthetic informed not by academic traditions but by what to his eyes were more natural, instinctive, and authentic impulses, that equated to some innate sense of Spanish identity.

Newly reconnected with some primal sense of his own ancestry, Picasso’s portraits of Fernande, and of Gósol’s innkeeper Josep Fondevila, are imbued with qualities that he observed in ancient Iberian art. A fragment of an ear, carved in limestone and dating from the 2nd-1st century BCE, is suggested as the source for Fernande’s ear in Head of Woman, 1906. Painted on wood, and simply delineated in earth colours, the painting has an unmistakably archaic quality.

Half-nude with a Jug, 1906, with its earthenware vessels and partially clothed figure is similarly timeless, and refers not only to the ancient tradition of depicting women at their toilet, but in its profile view of Fernande, it echoes the fragments of relief sculptures found at Osuna only a few years previously.

According to the curators, Picasso was “fascinated and almost obsessed” with Josep Fondevila, the landlord of Cal Tampanada where he and Fernande lodged that summer. Picasso saw in him “a strange and wild beauty”, and his aged, angular face was well suited to the emulation of an ancient Iberian idiom.

More recent precedents were key to Picasso’s experiments in Gósol, not least the work of his hero Paul Gauguin who had died in 1903. Gauguin was the only artist of his generation to make sculptures in wood, in which he emulated the indigenous styles of the Pacific Islands. Such examples may have been on his mind in Gósol, where medieval Catalan sculpture, such as the Madonna in the local church seems to have inspired Picasso to take up wood carving, the roughly hewn body of his Bust of a Woman (Fernande), 1906, contrasting with its finely wrought, but schematic head.

Back in Paris, and clearly enthused by this new direction in his work, Picasso produced some of his best-known portraits, of the American writer and collector Gertrude Stein, and also of himself.

The portrait of Stein was begun in 1905, but abandoned after more than 80 sittings, the masklike face completed from memory in the autumn of 1906, on his return from Gósol.

In it, as with his self-portraits from the same time, he combines the hard outlines, and inscrutable expressions familiar from Iberian sculpture, with a strong sense of individual personality.

At the same time, he launched into an exploration of the female nude, using strong lines and geometric forms in figures that have a solidity strikingly similar to Iberian examples.

Sculptures in wood and stone made in the spring of 1907 seem to be in direct response to the two stolen statuettes he acquired at this time, the simplification of form seen in these examples translating across to paintings, such as the Woman with Clasped Hands, 1907, in which the figure is reduced to a series of arcs, ovals and triangles.

These, and some 16 sketchbooks filled with studies, paved the way for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, but also for the work that followed, which became ever more linear and geometric, as Picasso moved towards what we now recognise as cubism.

Alarmed by their brush with the law over the theft of the Mona Lisa, Picasso and Apollinaire briefly considered dumping the stolen statuettes in the Seine, before deciding instead to return them via the newspaper Paris-Journal. The return of the statuettes did not signal an end to Picasso’s interest in Iberian art, however, and the exhibition relates his increasingly abstract figures of the late 1920s onwards, to small bronze figures of which Picasso eventually acquired examples for his own collection.

Equally, his longstanding interest in bulls, warriors and acrobats stems at least in part from Iberian examples, while The Kiss, 1929, seems to be directly related to a relief sculpture of the same subject from Osuna.

Later in his career, Picasso’s work had largely moved on from the overt emulation of archaic art, though his decorated cooking pots of 1950 are an exception, and even the most “modern”-looking of his ceramics from the 1940s and 1950s are steeped in the influence of the distant past.

For Picasso, who must have felt his foreign, Spanish identity particularly keenly during his early years in Paris, ancient Iberian art provided not only a fresh new precedent, but a deep connection to his own ancestry and sense of self, that found its expression in a style that has ultimately become unmistakably his own.

Who really stole the Mona Lisa

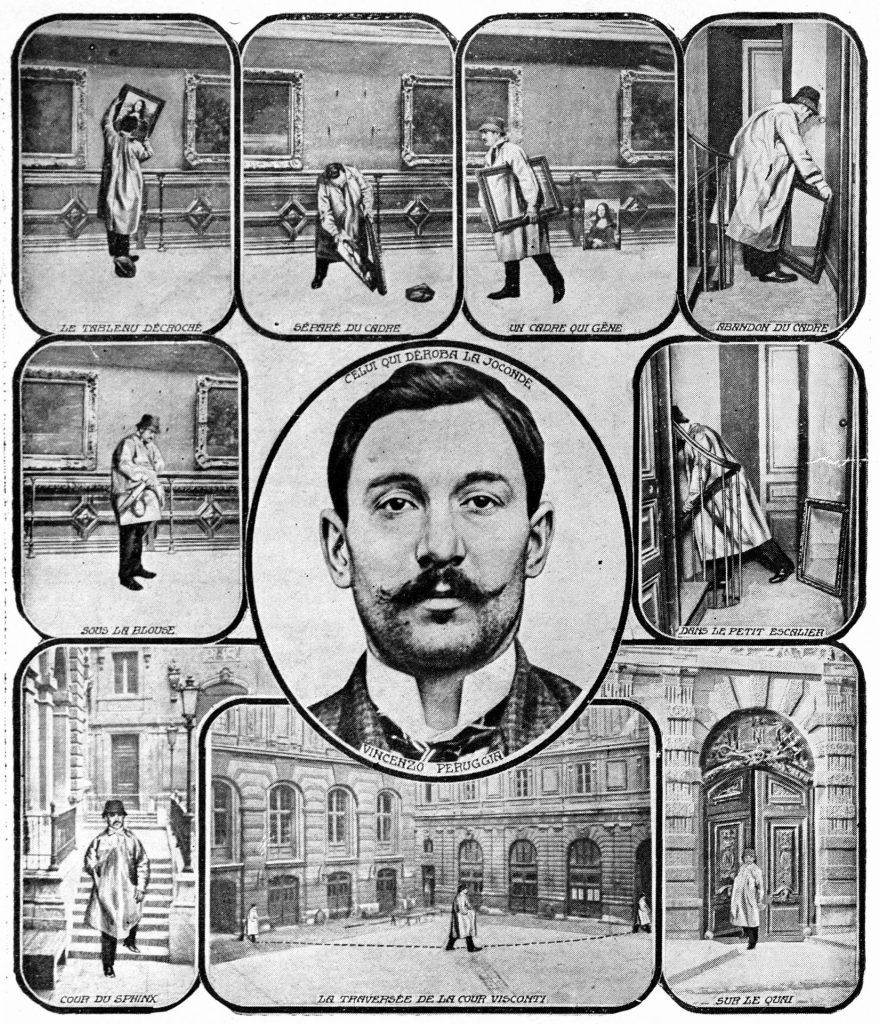

Pablo Picasso did not steal the Mona Lisa. Instead, an Italian former Louvre worker named Vincenzo Peruggia did. Acting either from greed or, as he claimed at his trial, a burning sense of patriotism and a desire to retrieve for Italy a work he falsely believed had been looted by Napoleon, Peruggia pulled off the theft on the morning of Monday, August 21, 1911, having hidden himself in an art-supply cupboard in the gallery overnight, dressed in the white smock he wore in his days as a museum staffer. Around 7.20am, Peruggia emerged from his hiding place, lifted the painting – ironically, in a protective glass case he himself had fitted during his time at the gallery – off the wall, stripped it of its case and frame, then covered it in a blanket. He took the painting down a staff stairway that led to the first floor, but found a locked door that could not be opened by the key he had kept from his time as a Louvre worker.

Luckily, another worker who presumed he was doing maintenance duties, opened it for him, and shortly after, Peruggia strode through the museum’s entrance, unmanned as the single guard had gone in search of cleaning equipment. Soon, he was at the Quai d’Orsay station, where he temporarily left the city.

Though the painting’s absence was noted by 8.30am, the fact that this was due to theft was not discovered until the following morning, when the museum reopened. A major project then underway involved the Louvre’s greatest works being taken to its roof to be photographed in daylight. It was assumed the Mona Lisa was away temporarily, and it was only after an amateur artist painting a still life of the gallery asked a guard to check when it would return that the alarm was sounded.

The incident because a cause celebre, with Picasso, American multi-millionaire JP Morgan and Kaiser Wilhelm all rumoured to have masterminded the painting’s disappearance. Arguably, it raised La Giaconda to its current status as the world’s best-known painting, although the fact that the Parisian police force detailed to track it down numbered 60 officers suggests it was already a pretty big deal. So too does the fact that the story made front pages worldwide, and that 28 months later, Peruggia attempted to sell the painting to a Florence art dealer for a “finders’ fee” of the equivalent of £1.5m in today’s money. He was asked to leave the painting with the dealer overnight until the banks opened, and when he returned for his money the police were there to arrest him.

At his trial, Peruggia refused to give up any possible accomplices – in its case it would have weighed 90kg, difficult for one man to lift alone – and was jailed for a year but released after only seven months as a bigger story had broken: the start of World War I. In 1916 he was captured by Austria-Hungary and held as a POW for two years until the end of the conflict. He returned to France where he died on his 44th birthday, in 1925.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37