The thousands of words, well-meant tributes and appraisals written about Gerd Müller since his death fail to address one intrinsic issue. Nowhere do we read that his passing was a release. His last six years were spent in a nursing home south of Munich, where he suffered increasingly acute dementia.

Heading a football is now believed to cause brain damage. Alcoholism is another cause of dementia. If you disbelieve the latter, read the Alzheimer’s Society website. “Alcohol consumption,” it states, “in excess has well-documented negative effects on both short-and long-term health, one of which is brain damage that can lead to Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia.”

Gerd Müller had a lot of help in his life from FC Bayern München, the club which gave him his platform and in return he gave them one of the most profuse amount of goals in sporting history. He was a one-off, Gerd. A short, squat fellow whose instinct for putting the ball in the net raised Bayern, and West Germany’s national team, to world acclaim over a sustained decade-anda-half during which no-one – absolutely nobody – scored more regularly or more reliably.

The fifth child of a Bavarian lorry driver, from a small town which was still under Allied occupation after the Second World War when Gerd was born in 1945, the father died from a heart attack when Gerd was 10. At 14, the youngest son left school to start an apprenticeship in a weaving factory. Five years later, Munich called.

The rest, as they say, is history. Or it was until that ended abruptly in 1979 when a new manager at Bayern gave him the thumbs down, literally. Müller had never felt rejection before and did not wait around for a slow decline to his career. He feared flying to the point where he needed a stiff whiskey to board a plane. But weeks after being substituted for the first and only time in his career, he was in Florida, joining Fort Lauderdale Strikers in the North American Soccer League.

It was nothing like the real thing. It was Hollywood in football boots. Franz Beckenbauer, his friend and captain at both Bayern and Germany’s national team played alongside Pelé in the New York Cosmos, financed by Warner Communications as an extension of the American entertainment industry. Trevor Francis, newly acclaimed as the first million-pound player, moonlighted for a summer with the Detroit Express, much against Nottingham Forest manager Brian Clough’s wishes.

And, obviously, the attempt to get football – soccer – off the ground in the United States meant an awful lot of flying.

At the most vulnerable time in his life, married and with a young daughter, Gerd Müller suddenly entered a different stage of his career, his life. He was paid a reported $80,000 a season, and actually bought into a restaurant, The Ambry in Fort Lauderdale. It catered for the German-American community, featured bratwurst and rib-eye steaks, and it exists to this day.

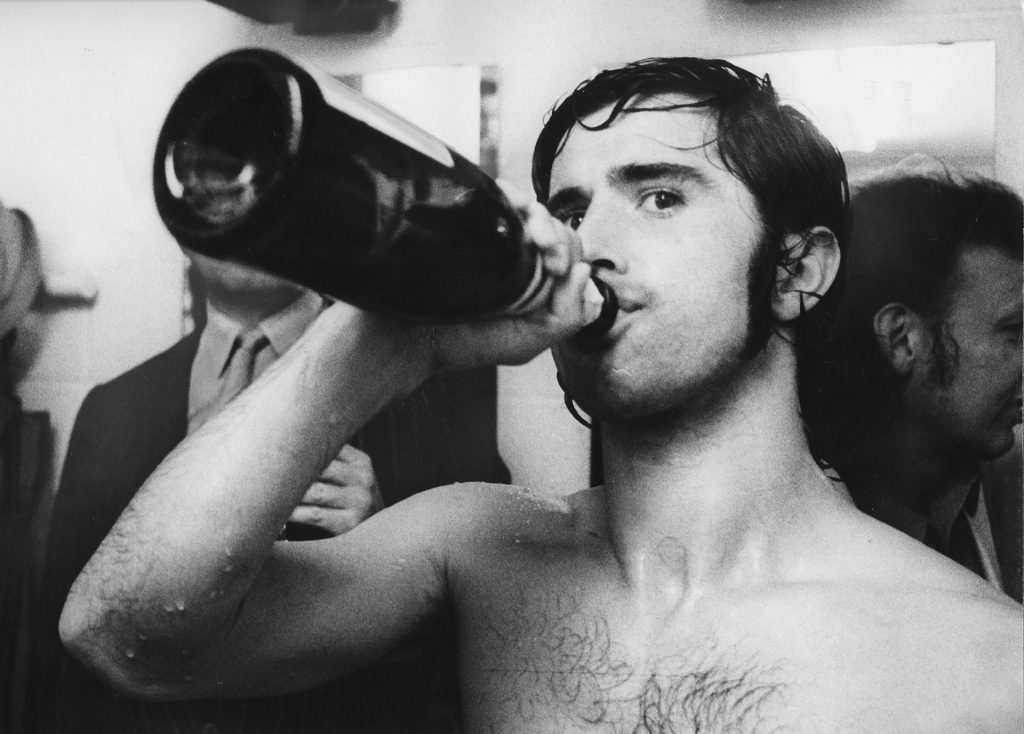

Retitled Gerd Müller’s Ambry, its nameplate emphasised “Steak & Spirits”. And reports soon circulated that mine host was both its best customer and spirits his best friend.

He was, in short, a declining footballer looking into a glass to fill the void. We read incessantly today of famous football stars of that era falling to dementia. The England 1966 World Cup winners, the Manchester United 1968 European champions one by one living with, or dying from, Alzheimer’s Disease which could be attributed to heading that old leather ball. Or it could be lifestyle. Or in some cases exacerbated by drink.

My own observation, having known many of these players, is that their careers should carry a health warning of another related aspect. Fame swiftly, suddenly, inevitably followed by sudden withdrawal.

Their lives are consumed by their “game” although the glamour of it masks the effort to sustain their skills, to stay whole in body and mind, and to stay focussed and “normal” when they are in the bubble of celebrity. Think of Garrincha, the “Little Bird” on the wing of the great Brazil side that launched Pelé’s global acclaim; Garrincha, like Müller, was a legend in the first third of his lifetime. A natural, spontaneous, matchwinning winger. Garrincha died aged 49 in an institution for alcoholics. A haunting message at the end of his bed read “name unknown”.

A different interpretation might have been that he fell into the disorientation that came after the playing had to stop. The withdrawal. Widen that concept: Consider Diego Maradona and his drugs to premature death story. Consider Edith Piaf, Elvis Presley, or Willie Pastrano. Was celebrity their lethal cocktail, or was it the unpreparedness for withdrawal once the roar of the crowd stopped?

Pastrano was an acclaimed American light heavyweight until either he took too many punches, or he simply aged. Either way, he tried to fill the void in the aftermath of boxing with, among other things, drink and dope. “It wasn’t the heroin I wanted,” he told a criminal court judge. “It was the boxing thing. Boxers should be rehabilitated like Vietnam veterans.” It wasn’t the punches, Pastrano insisted, “it was the applause.”

Has anybody better articulated the withdrawal syndrome than the ex pugilist? Müller to my knowledge never had public words for most of what happened in his life. He did, however, have three friends – Uli Hoeneß, Franz Beckenbauer and Karl-Heinz Rummenigge who not only shared the field with him but developed the business acumen to run Bayern Munich and to turn it into arguably the best-managed football enterprise in the sport.

They combined their knowledge of playing the game into hard-nosed business, knowing how and when to sign the best payers in Germany for the least amount of money. They knew there was no template for another Gerd Müller, but they waited until the next best thing, the Polish striker Robert Lewandowski, came out towards the end of his contract with their main rival, Borussia Dortmund.

They signed Lewandowski for nothing, paid him a wage no other Bundesliga club could, and built the team around him to feed Lewi the opportunities to challenge and even surpass their old friend Gerd.

Not that the trio in any way abandoned Müller. They brought him back from America. Back from the bottle. Back to his wife and daughter who had left Florida and returned home to Bavaria. Hoeneß in particular knew the flaws of being an ex-pro. And the three famous ex-players by then running their club made an uncompromising deal with their mate: They would pay for treatment in an Austrian clinic to wean him off the drink, and would then offer him roles from junior coaching to greeting guests back in Munich on condition that he gave it everything – absolutely his all – in breaking his addiction.

He did, and they kept their side of the bargain, ultimately until his death at 75 in the best care home anyone had heard of just south of Munich after his dementia was diagnosed almost six years ago. Even as their own time, and in the case of Beckenbauer personal health withered, the comradeship, care and responsibility the three Bayern big wigs showed towards Müller and his family have to rank as one of sport’s most endearing redemption stories.

And hearing Hoeneß give a farewell address from the centre of the pitch – typically praising Frau Ursula (Uschi) for her devotion to Gerd’s dying day – emphasised even further the bond between football, family and club.

That, and illuminating the Munich stadium with the simple message “Danke, Gerd!” surely meant more than references to Müller as the Muhammad Ali of football. Or to the Covid-restricted commemoration ceremony back in his birth town Nördlingen, the Bavarian town north of Munich where a candle was embossed with him depicted wearing a crown and the inscription “the eternal king of football”. Or to the book of “digital condolence” to remember the “Bomber der Nation”.

He apparently disliked the description – not because of the wartime connotation for someone born in a southern German town in 1945 – but because Müller believed it implied a brutish power rather than the consummate scoring machine that he was.

Knowing he could score from any angle at any moment was no shield against him. I once conveyed a personal apology to Gerd from Europe’s most accomplished footballer of their era, Johan Cruyff. It was the eve of the 1974 World Cup. Cruyff and I collaborated on a series of articles for The Sunday Times in which the Dutch captain, using a prototype of the Sony Betamax home video cassette recorder, studied the outstanding player from each of the 16 nations of that tournament.

Cruyff surprised me by choosing Müller, not Beckenbauer, as the key man of the then West German team. “I know, I previously said Müller isn’t a footballer, only a goal scorer,” Cruyff explained. “But he has something others do not. How he scores is unbelievable – always from 11 metres. He’s not tall, but he gets every ball in the air. Look at how he scores when any other player would lose balance.”

I suggested to Cruyff that Müller had an inner sense, like a homing pigeon. Gerd could not explain it, so how could opponents counteract him? “I have an instinct,” Müller had said, “Something inside tells me says Gerd go this way, Gerd go that way. And the ball is coming and I score. I don’t know what it is.”

It could only be called instinct. “Yes,” Cruyff agreed. “I too have reactions, feelings I cannot explain.”

When I passed this on to Müller, he simply smiled. He bided his time. And he scored the decisive goal to win the World Cup final, against Cruyff ’s Netherlands.

Simple, but neither a simpleton nor the unfeeling sniper, the Bomber, he was reported to be.

It took an age for giant talents like Brazil’s Ronaldo de Lima (1998-2002- 2006) to eclipse Gerd Müller’s World Cup goals record. Robert Lewandowski this year pipped the 40 Bundesliga goals in one season for Bayern set by Müller 49 years previously. And Müller’s calendar year record of 85 goals for Bayern and Germany in 1972 finally fell in 2012 to Lionel Messi’s 91 for Barcelona and Argentina.

Müller’s goals in 1972 came in 60 games. Messi’s took 69 matches. No player beat Müller’s goals per game ratio for Germany (62 caps, 68 goals).

Messi is the most exquisite player of his era; Müller’s short, squat, stocky 1.76m (5ft 9) frame was mocked on first sight by his first coach at München. “You want me to put a bear among my thoroughbred racehorses?” Zlatko Cajkovski, the Croatian trainer asked the building contractor Wilhelm Neudecker who, as Bayern president, paid 4,400 Deutsch Mark (about 2,250 euros, less than £2,000) to take the part-time player, apprentice weaver from TSV Nördlingen.

Cajkovski somewhat more rudely called the 19-year-old “Kleines dickes Müller” – Short Fat Müller.

The trainer was made to eat his words. Once in the team, the phenomenon proved largely uncontainable, un-coachable and basically undroppable.

Just let him listen to the voice “Gerd go this way, Gerd go that” and leave well alone. That was Cajkovski’s way, and Helmut Schön’s – the nation trainer’s throughout all of the games the Short Fat irrepressible Müller played for Der Mannschaft.

Schön never dropped Müller, although Raimund Hinko, the veteran Munich correspondent for Sport Bild did reveal the inside story of the “Doppelzimmer von Franz Beckenbauer und Gerd Müller” during the 1974 World Cup.

Herr Schön was called to the double room shared by Beckenbauer and Müller to settle an argument over who plays centre forward, Gerd or Uli Hoeneß.

“Just leave Uli out!” Müller apparently demanded. Schön would do no such thing, Müller backed down and together they won the tournament.

“Good-natured, polite, mild, sometimes even disinterested,” observed Hinko, “but..before the 1970 World Cup he became a raging wolf. ‘Uwe [Seeler] or me,’ he said.”

Hinko wrote that “Soul Doctor Schön put him in a double room with Uwe.” Seeler, then 33, and Müller, 24, both scored in the victory where Germany came from two goals down to eliminate England, 3-2, from that World Cup in Mexico.

Müller, not Schön, called time on his international career after the 1974 triumph.

That was reported as a reaction to wives and girlfriends not being invited to the post-tournament banquet; in fact Müller told the coach before the final that win or lose, he would finish at the age of 28.

Portent, perhaps, of the strain of being such a “natural”. The phobia of flying, the burden of fame, ultimately the player who could score quicker than others might blink fled the burdens of fame.

Rest in Peace, Bomber.

The Bomber’s Golden Decade

1966/67

Scores four goals in a two-legged semi to put Bayern into the European Cup-Winners’ Cup final; they beat Rangers 1-0 in extra time for their first European trophy. Bayern also retain the D F B-Pokal, the German Cup and Muller shares the Torjägerkanone, the Bundesliga Golden Boot – the first of seven times he will win the award. Voted German footballer of the year. Opens his international account with a brace in a 6-0 win against Albania; he will go on to score 68 goals in 62 games for West Germany

1967/68

Bayern lose two semifinals and are fifth in the Bundesliga. But Muller still scores 30 goals

1968/69

Miller wins his first Bundesliga, the Cup, the Torjägerkanone and is named German footballer of the year

1969/70

Wins Torjägerkanone and becomes the first German winner of the Ballon d’Or. Scores ten times, including the goal that knocks out England, at the World Cup finals

1970/71

Scores 39 goals in all competitions as Bayern win the Cup Bundesliga on the final day.

1971/72

Bayern win the league as Muller breaks the single-season Bundesliga record with 40 goals, a mark that will be held until Robert Lewandowski scores 41 in 2020–21. Scores twice in the European Championship semi-final and twice again in the final as West Germany beat the USSR 3-0; top scorer in the tournament.

1972/73

Bayern retain the league title and Muller retains the Torjägerkanone. He’ll win it for a final time in 1978. Muller then scores twice as Bayern win their first European Cup final, beating Atletico Madrid 4-0 on May 15 in a replay. He scores only three times in the World Cup, but one is a trademark spin and finish for the winner in the final against the Netherlands on June 7. He then controversially quits the national side.

1973/74

Bayern retain the league title and Muller retains the Torjägerkanone. He’ll win it for a final time in 1978. Muller then scores twice as Bayern win their first European Cup final, beating Atletico Madrid 4-0 on May 15 in a replay. He scores only three times in the World Cup, but one is a trademark spin and finish for the winner in the final against the Netherlands on June 7. He then controversially quits the national side.

1974/75

Scores in the 2-0 victory against Leeds to win the European Cup again.

1975/76

Scores five goals in a European Cup campaign that ends with a 1-0 win against St Etienne in the final.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37