“… from molten gold the Israelites did fashion a calf to be worshipped. And the Lord saw it and the Lord’s anger did burn hot, but Moses sought the favour of the Lord and the Lord relented over the evil he said he would do the people. Moses went down from the mountain and he approached the camp and saw the people dancing and the calf of gold and Moses did become extremely angry …”

Heaven alone knows what Moses would make of Warren Ellis and his adoration of a piece of discarded chewing gum. But I think he’d give him a pass. How could anyone be pissed off for long with the author of such a wondrous book as Nina Simone’s Gum?

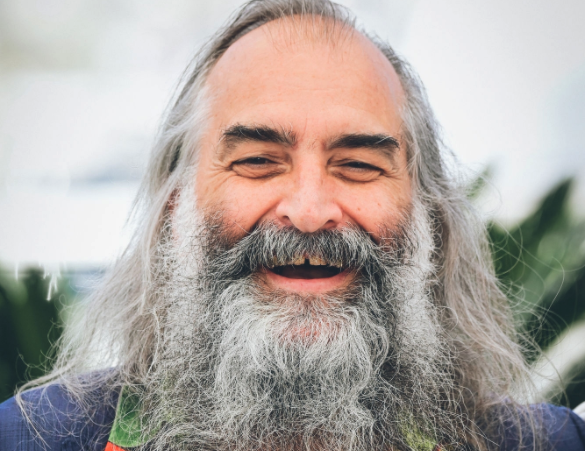

Ellis is an Australian musician; long-time collaborator with Nick Cave and multi-award-winning film soundtrack composer. Biblical facial hair is another reason for Moses to turn a blind eye to his apostasy.

Ellis is not – and this is the saving grace of his book, already into its third reprint – a professional writer. He’s better than that.

His book, and the many self-taken photographs that illuminate the oddness of the story, has a strange, mystical, quality transcending storytelling; it is a case study in existentialism. In places it reminded me of the first half of Robert M. Pirsig’s Zen And The Art Of Motorcycle Maintenance, before stuff turns dark.

I was recommended Nina Simone’s Gum by two friends on the same day, the definition, I guess, of good word of mouth. The story is simple; Ellis is present at one of Nina Simone’s final concerts and sneaks on stage as she leaves to requisition a piece of used chewing gum she stuck to her piano.

He folds it carefully in the white towel she used to mop her brow and secretes it away in a yellow Tower Records bag, preserving it, sacred and secret, for twenty-odd years before casually mentioning its existence to Cave, at which point the piece of chewing gum takes on a life of its own, becoming a central exhibit, with its own marble plinth and its own insurance policy, in an international exhibition called Stranger Than Kindness.

Before that, fearing it will be lost, the gum is painstakingly replicated in silver and gold, scanned in 3D so it could one day be reproduced to the scale of a building in which Ellis imagines himself living.

If all this sounds utterly nuts, don’t worry, it is. But it’s wonderful with it.

Ellis is a collector. He forms extreme attachments to objects, granting them considerable influence over his life; an extreme example of most of us … anyone who ever saved an object because it gave them a breadcrumb trail out of the labyrinth of our lives, back to some kind of comfort.

His micro-attentiveness to passing details of life seeps through the book. Sometimes with great comic timing (he’s on the way to buy bathroom taps, he finishes watching The Sopranos), sometimes as though he, literally, sees something hidden from the rest of us (the ghost of Beethoven, clowns in his childhood garden). It all accumulates into something with the quality of a lyric.

His narrative is punctuated with occasional lists of cherished objects. A marble made of marble gifted him by Greek singer Arleta, a small model Eiffel Tower (“of which I own more than twenty”), a particular brand of Samsonite briefcase, busts of Beethoven.

All objects he cherishes and relies on in his journey from birth in the highlands of Victoria to international fame and success via spells down and out in Paris, London … and Banffshire.

But Nina Simone’s gum is the holy of holies and Ellis’ separation from it, as it prepares for its starring exhibition role, is the basis of this beautifully-told inquiry into meaning and meaninglessness.

Throughout this remarkable book, all those who come in contact with the gum become pathologically obsessed with its protection. Ellis attributes this, sincerely I have no doubt, to its connection to Nina Simone.

But it seems to me the enormous devotion these various caretakers display to its safety and preservation is rooted mostly not in reverence for the relic, nor even Nina Simone, but rather an appreciation of, and deep care for, Ellis.

It’s not Nina Simone’s gum after all. It’s really Warren Ellis’s. Always was.

Nina Simone’s Gum is published by Faber. Available widely.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37