There are many ‘what ifs’ in British political history. Most are meaningless. On the whole, we can not know what might have happened if X had become prime minister rather than Y.

There is more than enough happening in front of our eyes without spending time speculating about alternative dramas. Nonetheless, when writing a book about 11 prime ministers we never had, I became certain that one would have changed the course of British history.

My book is an investigation as to why those that were seen as possible or probable prime ministers failed to reach Number Ten. My inquiry begins with the brilliant and weighty Rab Butler and ends with Jeremy Corbyn, who after the 2017 election was briefly seen as a possible PM.

Even in the case of Corbyn, we cannot be sure he would have been an historic game-changer. If he had been prime minister he would have almost certainly ruled in a hung parliament while facing the pandemic and Brexit. He might have been swept away by the hurricanes, perhaps to his relief. We do not know.

We can explore why he and others who were more qualified failed to get to the top. The evidence is available for us to make an assessment. We cannot speculate confidently about what might have happened.

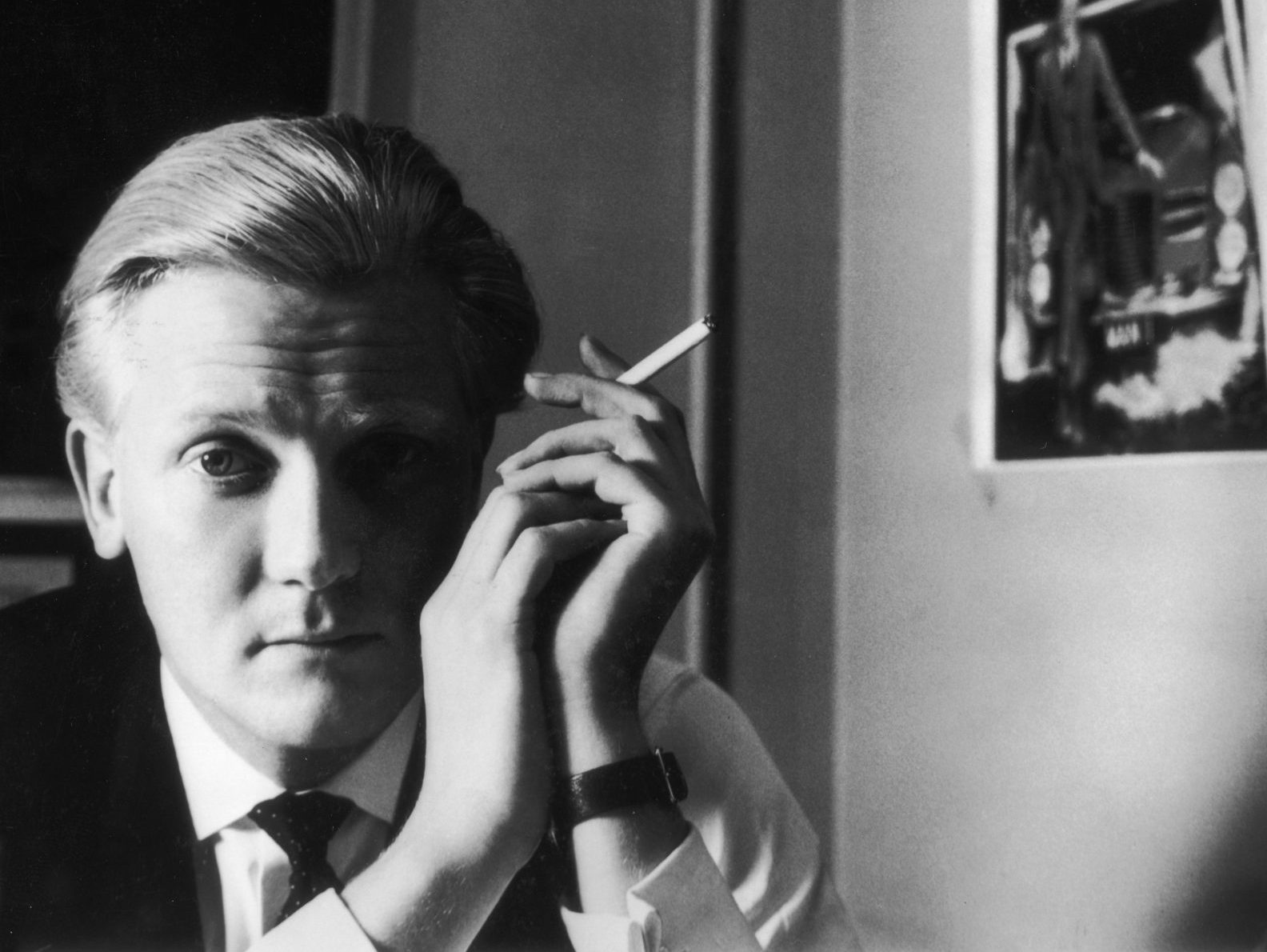

There is one exception. Of the 11 PMs we never had, I assert Michael Heseltine would have changed the course of British history. Had he been PM, what has happened would not have happened.

The UK would still be in the European Union, the term Brexit would never have been coined and the Conservatives, like all mainstream parties across the EU, would have broadly recognised the advantages of being a member.

Although there was feverish speculation about Heseltine’s prime ministerial ambitions throughout his career he only fought one leadership contest, the one in November 1990 when he challenged Margaret Thatcher.

This is quite common with the prime ministers we never had. They are burdened by talk of their driving ambition and yet fight a single leadership contest in their entire careers. In Heseltine’s case, he cleared the way for John Major to become PM and never made a further attempt to reach the top.

If Heseltine had won in 1990 he would have been an unambiguous pro-European Conservative prime minister. There would have been no equivocations from him on this policy area. He was as unyielding as his colleague, Ken Clarke, another PM we never had.

Clarke did not become Tory leader either. By the time he started to challenge in leadership contests, his views on Europe were too far removed from his party’s. But that was from 1997 onwards.

Heseltine made his move seven years earlier. In 1990 a section of the Conservatives had become much more Eurosceptic under the leadership of Thatcher but its hostility was far from fully formed.

Indeed Thatcher’s Shakespearean fall arose partly from her increasingly strident attitude to the EU. The main focus of Geoffrey Howe’s famous resignation speech that triggered her removal was on her aggressive approach to Europe.

She fell partly because she was too hostile to Europe, not because she was too soft. The Tories were in a state of unresolved flux in 1990.

Thatcher had never advocated leaving the EU and had signed up to every EU treaty while PM. There was not a single Conservative MP advocating leading the EU in 1990. A significant minority of Conservative MPs were opposed to the Maastricht Treaty, but none of them wanted to leave the EU.

Heseltine would have taken them on. There was no other course available to him with his convictions on Europe, as passionate and as firmly held as Edward Heath’s, the PM who took the UK into Europe. If Heseltine had become prime minister in 1990 he would have won the 1992 election as Major did, probably by a bigger majority. He was a much more effective campaigner.

Heseltine would have then secured a personal mandate to challenge the more militant Eurosceptics. Some might have left the Tories. The battle would have been bloody.

It is the battle that needed to happen for the Conservatives, in the same way that Neil Kinnock had no choice but to challenge the likes of Militant in the 1980s as Labour leader. Europe was the party’s fault line and there was no way around it. Major tried to keep everyone on board but merely fulled Eurosceptic militancy. David Cameron opted for appeasement. It had fatal consequences, not least for his leadership.

If Kinnock had become PM after the 1992 election he would have led a government and party more or less united in their support for the UK’s membership of the EU, in marked contrast to Major’s administration.

But the Conservative Party might have won subsequent elections and still taken the UK to the position it is in today. Similarly, if Ed Miliband had won the election in 2015 he would not have held a Brexit referendum, having courageously opposed the policy in the election.

But Labour had earlier backed the coalition’s legislation that guaranteed a referendum on any future EU treaty. This was also a route towards Brexit, as any such referendum would probably have rejected a new treaty.

Like Heseltine, Kinnock and Miliband are significant and complex prime ministers we never had. Their governments would have made the UK a different place in ways that we will never know for sure. But they might not have stopped Brexit given that the Conservative Party tends to win most general elections in the UK. Only Heseltine had the will to stop the move towards his party becoming the Brexit party.

There is an argument that Heseltine would have tried and failed to change his party. This view underestimates the power and authority of a prime minister in their early honeymoon phase, assets that Theresa May squandered when she was 20 points ahead and her cabinet were in subservient awe.

Heseltine would have had space from 1990 to guide his party towards a more pragmatic position. There were plenty of Tory MPs who were sceptical but willing to be persuaded that being part of the EU was in the UK’s interests, not least with a PM using his powers of patronage as well as his persuasive skills to sway them. By 1997 the party had changed and the cause was lost.

In 1990, Europe barely featured in the leadership contest, a battle fought by three pro-Europeans, Heseltine, Major and Douglas Hurd. From 1997, Europe defined who was to lead the party. William Hague was elected as a Eurosceptic. So was Iain Duncan Smith. Cameron even pledged to pull his party out of the centre right grouping in the European parliament to woo his Eurosceptics.

Only Heseltine had the character and the near presidential demeanour to reverse the tide when the currents were still fairly weak. He would have done so. Almost certainly given his indecision over what to do in the Brexit referendum, one of those to follow the alternative Heseltine tide would have been Boris Johnson.

When Heseltine failed to become PM in 1990, the UK began its painful journey towards the hardest possible Brexit.

- Steve Richards’ The Prime Ministers We Never Had – From Butler to Corbyn is out now from Atlantic Books

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37