King Alfonso XIII of Spain was a conundrum. On the one hand, he manifested the patrician comportment of so many of Europe’s hereditary monarchs which led to revolution across much of the continent throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.

On the other he was a proponent, in words at least, of constitutional monarchy and limited liberal democracy; a humanitarian nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1917 for charitable work during the First World War.

Irony, indeed, then that history can draw an almost direct line from Alfonso to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, five years after he fled the nation – a war which still shapes and scars the face of politics in Spain today.

The rise of Spanish republicanism, its far right adversaries and the eventual dictatorship of General Francisco Franco, all can be placed at Alfonso’s door. And that’s because he had another trait all too common to hereditary monarchy – vanity. A hundred years ago this summer, it would occasion his downfall.

As the 1920s approached, Europe’s colonial project in Africa had pretty much run out of steam. Populations no longer wished – if indeed they ever did – to be ruled from European capitals by kings, dictators or ministers whom they had never met and had neither knowledge nor interest in their lands or culture.

North Africa, especially, was in a state of flux. Driven by the cataclysm of the First World War, colonial rule was grinding to its painful denouement. Spain and France had long held territory in the nation we now call Morocco, but its disparate peoples were fighting back.

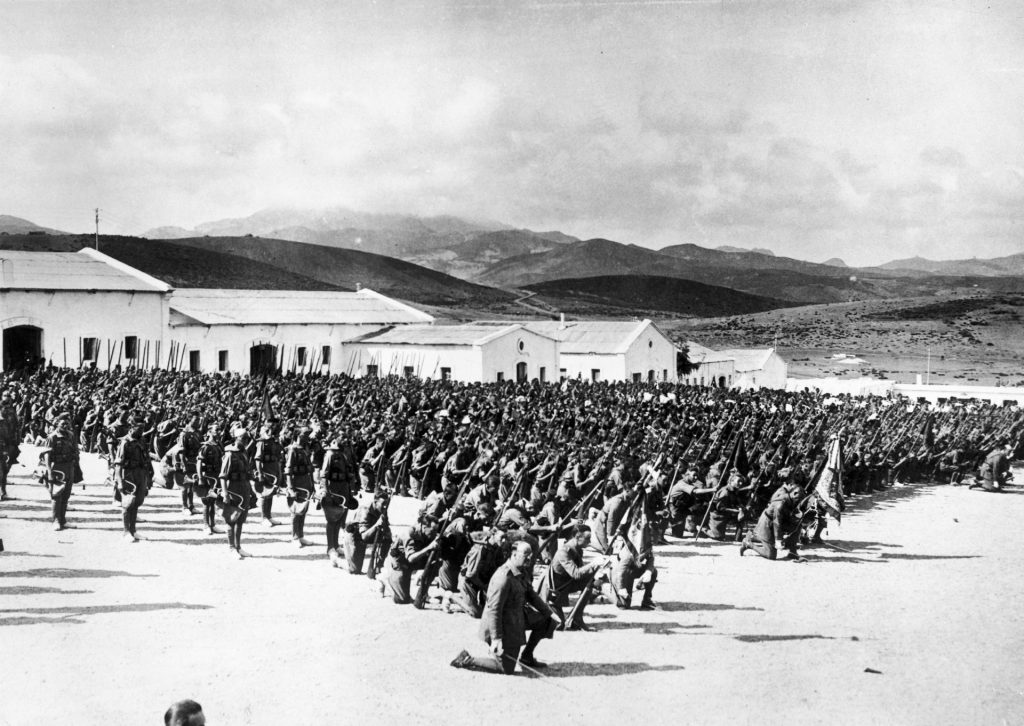

War between the Spanish and Berber tribes of the Rif mountains broke out in 1921 and, for the former, it would be a turning point not just in their colonial ambitions but in the future of their entire nation.

Heavy defeat to the United States in the Spanish-American War of 1898 had seen the end of Spanish rule in the Americas and the loss of territories – notably the Philippines – in the western Pacific. Humiliated and in hock to French military support in Morocco, Alfonso was desperate to save face.

At home, facing the rise of republicanism, an economy in freefall, and protests fuelled by poverty and unemployment, Alfonso would see 33 different governments come and go between 1902 and 1923, yet his constant interference in parliamentary business only exacerbated his dwindling reputation.

The king decided only an outstanding military victory would deflect attention from domestic woes and international embarrassments and was prepared to go behind his parliament, the Cortes, to get it.

The Feast of St James – Spain’s patron saint – falls on July 25. Following the outbreak of the Rif conflict, Alfonso sent a telegram to General Manuel Fernández Silvestre, commanding a division near Annual in the Beni Ulicheck valley of northeastern Morocco.

Its first line read “Hurrah for real men” and demanded Silvestre launch an attack against Rifian Berber guerrilla strongholds. Victory would be announced on the feast day.

It was a catastrophic error. While the arguments for and against have been debated many times over regarding a battle that very few beyond Spain or Morocco have heard of, there is a case to be made that, via the vicissitudes of political fate, the events of summer 1921 led directly to the Spanish Civil War 15 years later and the totalitarianism of Franco.

The Battle of Annual, which began on July 21, was an unmitigated disaster – a mixture of ineptitude and vainglorious overreach. “A classic example of military incompetence,” wrote historian Antony Beevor.

The Rifs under Muhammad Abdel Krim al-Khattabi, more commonly known as Abdel Krim and once a civil servant with the colonial regime, routed the invaders.

The Spanish were more than 100km from their coastal base in Melilla with no supply lines or communications, but Silvestre was pugnacious and eager to please the king.

He also went against the orders of his commanding officer and warnings of retribution from Abdel Krim. The upper estimate is that Spain lost 22,000 troops at Annual and in subsequent fighting as they retreated to Melilla, most of the casualties barely literate, ill-trained and ill-equipped conscripts ridden with typhus or malaria. Exhausted and with morale extinguished, their retreat descended into chaos.

By comparison, only around 800 Rif guerrillas were reported dead. Disgraced, Silvestre almost certainly killed himself, although his remains were never found.

As an act of antonymic national self-aggrandisement Annual probably has no historical equal. In the Congress of Deputies, prominent socialist Indalecio Prieto said: “The campaign in Africa is an absolute failure of the Spanish army, without extenuation.”

Alfonso became known by critics as “the African dolt” who only fuelled outrage by declaring in the wake of the battle that “chicken meat is cheap”. Holidaying in France, he did not return to meet families of those killed, nor offer to pay ransoms for those captured.

Throughout Spain there was overwhelming anger towards Alfonso and the torpid generals living their comfortable colonial lifestyles, alongside sympathy for the lice-ridden, underfed conscripts.

As the Rif war continued and Spanish losses mounted, public opinion swung. The following year the Cortes began an investigation into what the Spanish now call the Disaster of Annual (Desastre de Annual).

Alfonso was implicated but prior to the report’s publication in 1923, soldiers embarking for Morocco mutinied while protestors in Barcelona and elsewhere simultaneously waved Rifian and Catalan flags and burnt Spanish ones.

The military turned. On September 13 Alfonso’s captain-general in Catalonia General Miguel Primo de Rivera seized power. The king was outflanked but, believing the coup would divert the public from the damning report, offered his support.

It allowed him to cling to his position as head of state as de Rivera became de facto dictator, suspending the constitution and establishing martial law.

In many ways de Rivera was fortunate. The monarchy and previous administrations had proved so incompetent that his assumption of power was generally accepted by the liberal middle class who felt nothing could be worse than the disorder of the last few years. They also accepted de Rivera’s reforms of the military intended to win the war in Morocco and cement the army’s position in Spanish society.

One immediate beneficiary was a young officer from Galicia. He was second-in-command of the Spanish Foreign Legion and responsible for the relief of Melilla, on the north African coast, besieged by Rifian forces following the rout at Annual, Francisco Franco.

Sergio Barua a soldier in his force said of Melilla: “My memory is the smell, the corpses, at every step a dead body, every step more horrible.” But Abdul Krim failed to press home his advantage, realising other nations had citizens inside Melilla.

His hesitancy allowed Franco to effectively save thousands of terrified, starving civilians and 1800 disease-ridden troops. He was promoted to lead the Foreign Legion and then to general, Spain’s youngest.

His stock grew, as did the brutal reputation of his Foreign Legion.

Facetiously nicknamed “the bridegrooms of death” it saw itself as saviour of the real Spain, especially among colonialists and monarchists. Conversely, it represented a nationalism that progressives in Spain found increasingly distasteful.

De Rivera’s regime, initially successful, stagnated as public opinion continued to mount against overseas campaigns. Consequently, government support for the Africanista army in Morocco, especially the Foreign Legion, wavered.

Yet Franco’s role in ultimate victory over the Rifs – at the cost of possibly 43,000 Spanish soldiers alongside French counterparts – achieved with the morally dubious practice of bombing and gassing Rifian villages using German ordnance, brought him to even wider prominence.

Back home, facing unemployment, agrarian and trade union unrest, allegations of corruption, the rise of the republican left and Basque and Catalan nationalism, de Rivera’s government collapsed in January 1930 – he died two months later.

The following year democratic elections saw socialists and republicans triumph. The Second Spanish Republic was declared, the military at home withdrew its support for the monarchy – bringing it into direct conflict with its colonial counterparts in Africa – and Alfonso fled to Italy.

Spain was now deeply divided. On one side were the Africanistas, monarchists, fascists, landowners and the rural areas of north and north-west Spain (including Franco’s home region Galicia) who ascribed to traditional values of the Catholic church.

Nostalgia for the 15th-century Reconquista when Spain was reclaimed from North African Islamic occupation ran deep. On the other were socialists, communists, anarchists, the landless, trade unions and democrats who defended the legitimacy of the Second Republic.

Something had to give. Five years after Alfonso’s departure, emboldened by the rise of fascism elsewhere in Europe and perturbed by the formation of the left wing Popular Front coalition in the Cortes which, under prime minister Manuel Azaña, was reducing the influence of the armed forces, the military in Morocco attempted to reverse the democratic outcomes of 1931.

Convinced a communist takeover was imminent, the Africanistas mutinied.

Franco, initially unsure but primarily an opportunist, broadcast a declaration of rebellion from the Canary Islands whence he had been banished by a government hoping to clip his wings. Military leaders crossed from Morocco into mainland Spain.

Over the next three years the nation became a battleground for competing ideologies, its civil war dragging on until 1939, often as a proxy for antagonism between Hitler’s Nazis in Germany who backed Franco and Stalin’s Soviet Union supporting the Republic. “It was the first battle of the Second World War,” wrote historian Adam Hochschild. It touched the lives of every Spaniard – killing possibly half a million and mutilating or exiling many more. Franco was, of course, ultimately victorious and ruled until his death in 1975, 54 years after Annual.

The thread leading from Annual to the Spanish Civil War is, naturally, one knotted with ifs and buts. History could have veered in any direction over the intervening years and Franco was as much an unwitting actor as he was a master auteur.

Every war has causes and consequences and so many led to the onset of the Spanish Civil War. Nonetheless, had Alfonso XIII not been so desperate to swagger before his subjects and failed so spectacularly in the execution, Francisco Franco might just have remained a footnote in Spanish military history.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37