It all began with a fight over handbags, but the glittering feud between France’s richest men has now entered a spectacular new phase.

François Pinault (the businessman behind Gucci, Christie’s and Yves Saint Laurent) has given himself the luxury of a public victory in his 22-year long private war with Bernard Arnault (Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Bulgari, Givenchy and scores of others).

This summer, Pinault, 85, opened a home for his art collection in an exquisitely restored 18th century building in the heart of Paris – giving the French capital a modest equivalent to the Frick Collection in New York or the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

The two men, once friends, fell out in 1999 in a battle for the ownership of the Italian leather goods company Gucci. They pursued their multi-billion pounds in recent years by competing to build collections of the best contemporary artists, from Jeffs Koons to Damien Hurst to Mark Rothko.

The rivalry has now escalated from works of art to private art galleries. Arnault, creator of Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy (LVMH), the world’s largest luxury goods empire, outflanked Pinault in 2014 by opening his own “foundation” in the Bois de Boulogne on the western fringes of Paris.

Pinault was furious. He had long dreamed of having a gallery in the capital to show off his collection of contemporary art – said to include more than 10,000 works by 380 artists.

In 2005 he abandoned an attempt to build a private museum on the Ile Seguin, an island in the river Seine just outside the French capital once entirely occupied by a Renault car factory. He complained at the time that the French art establishment detested any challenge to the state and municipal domination of the museum industry.

The Breton billionaire, who turned a small timber business into the world’s second-biggest luxury goods conglomerate, was obliged to console himself with two private Pinault galleries in Venice.

No longer. François Pinault (a football fan and owner of his home-region club Ligue 1 club Stade Rennais) has not only scored the equaliser in his contest with Arnault. He has taken the lead.

He has invested 108m euros on the restoration of a beautiful but long-neglected, late 18th century circular building close to the Louvre and the Centre Pompidou in the centre of Paris. The Bourse du Commerce, once the place where French wheat and barley were traded, has been turned by the Japanese architect Tadao Ando into ten flexible light-drenched spaces for displaying art – 6,800 square metres in all.

The inaugural exhibition contains the work of 32 different artists from Pinault’s collection, including 30 works by the African-American artist, David Hammons.

The centre-piece is a giant candle – a wax reproduction by the Swiss artist Urs Fischer of a 16th century statue of the capture of the Sabine women. The “candle-statue” will burn to nothing in the coming weeks. Since Pinault is the owner of Christie’s auction house and one of the world’s most prolific art buyers, this is a surprising and subtle commentary on the permanence and value of art.

The seven-year-old Louis Vuitton foundation in the Bois de Boulogne is double the size of the new Pinault museum – 13,500 square metres. It is a work of art in itself, a “deconstructionist” tangle of a dozen glass domes by the Canadian architect Frank Gehry.

The foundation has been a reasonable success. It is, however, far from the centre of Paris and not easily reached by public transport. Louis Vuitton provides a free shuttle of tiny electric buses to carry visitors from a private bus stop near the Arc de Triomphe.

The new Pinault exhibition space is a short stroll from the Louvre, Les Halles, Notre Dame and the Marais. Location, location, location. When tourists return to Paris post-Covid, the Pinault exhibition will almost certainly overshadow Arnault’s foundation out in the woods.

Officially, the feud between two of France’s richest men (and the world’s 2nd and 32nd richest) ended more than a decade ago. Nicolas Sarkozy, when president, brokered a lunch meeting between the pair in 2009.

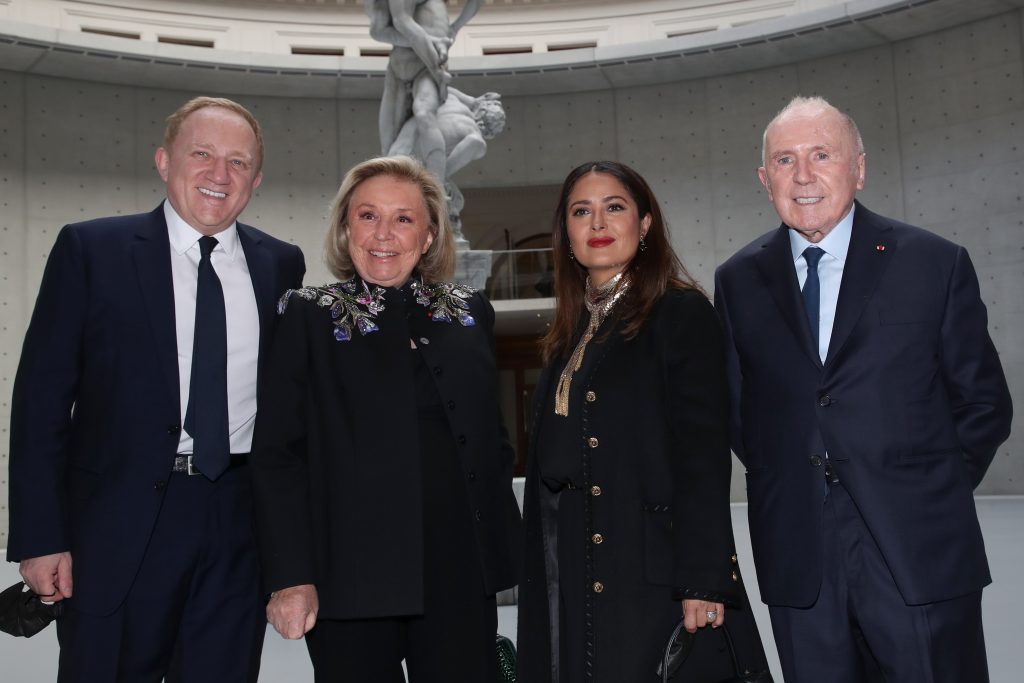

When the Louis Vuitton foundation opened, Pinault was given an advance private viewing. He returned the favour last month by inviting Arnault to preview his resurrected Bourse de Commerce.

Were these friendly invitations or acts of passive-aggressive one-upmanship between hyper-wealthy ex-friends? “Would you like to take my new custom-made sports car for a spin? Would you like to visit my personal art gallery?”

The men have similar life stories but very different personalities. Arnault is an urbane socialite and talented pianist. Pinault is reclusive, speaks with a rural Breton accent – but has a genuine and voracious knowledge of contemporary art.

Both men are provincials from outside the established French tribes of old wealth and influence, Pinault from the south-eastern corner of Brittany, Arnault from Roubaix on the Belgian border. Both turned deeply unglamorous family businesses – road repairs in the case of Arnault; timber-trading and farming in the case of Pinault – into luxury goods empires.

Both stumbled into the luxury business almost by accident. Arnault bought the Christian Dior brand as part of a fire sale of a struggling French textile giant in 1984 when he was 35. He controversially closed down or sold off the textile-making parts of the business and used Dior as the first building block in a luxury empire which now employs more than 120,000 people around the world, including 22,000 in France.

In the Forbes ‘real time’ global rich list, Arnault and family come second to Jeff Bezos of Amazon with an estimated fortune of $187.5bn. So much for France being an unenterprising country where it is impossible to grow rich.

Pinault is from an even more modest background. Arnault went to the Polytechnique engineering school, one of the breeding grounds of the French elite. Pinault left school at 16 to work in his father’s wood business.

He married ten years later into another much bigger wood company which he turned into one of the powerful in Europe before moving into retail and mail order (Printemps, Conforama, FNAC).

In the Forbes list, Pinault and family come 32nd with a fortune of $59bn, half that of Arnault. In France, he is usually third, just after Françoise Bettencourt-Meyers and family, owners of the cosmetics giant, L’Oréal.

The two billionaires were once friends and attended each others’ children’s weddings. They even lived in the same building in Paris.

That all changed in March 1999 when leading figures in Gucci, including its American designer Tom Ford, grew suspicious of the large, minority shareholding which had been acquired by Arnault and LVMH.

They increased Gucci’s capital and invited Pinault to buy up all the new shares, diluting Arnault’s holdings but also those of other shareholders. A two-year legal battle followed, settled in court, but Gucci remained under Pinault’s control.

He used the Italian-based company as the foundation of a new luxury conglomerate called Kering to rival LVMH. The pursuit of luxury brands by rival Arnault and Pinault empires in the last two decades is said to have pushed up the asking price of their targets by hundreds of millions of euros.

Something similar has happened in the art market. Pinault and Arnaud are far from the only super-wealthy collectors but their public rivalry has increased the price of works by artists like Koons, Hirst, Takachi Murakami, Subodh Gupta, Maurizio Cattelan and Richard Serra.

Art experts compare their competition to the inflationary bidding war for art in the 1960s between the Greek shipping billionaires Aristotle Onassis and Stavros Niarchos.

Opinions on Pinault’s motives as an art buyer differ. Despite his age and reclusive habits, he flies around the globe to visit artists and bombard them with well-informed questions. He also sells at a profit when the time is right. He bought Robert Rauschenberg’s celebrated painting Rebus in 1992 for $8m and sold it to the New York Museum of Modern Art for $30m in 2005.

“He is a hunter,” says the art expert Marc Blondeau, a frequent Pinault adviser. “Building up a mausoleum collection has no interest for him.”

Arnault, by comparison, is said to follow the opinions of his advisers. His collection is mostly the property of LVMH. It is often used to promote the image of the company and its individual brands.

What next in the war of the French billionaires? Pinault has seized the initiative. The clock is ticking on Arnault’s riposte.

Maybe the expensive candle burning in Pinault’s Bourse du Commerce is meant as a joke on his rival.