Into the grey battlements of London’s brutalist estate, the Barbican, steps a woman. The camera tracks her as she saunters sedately through lush foliage which cascades over the walkways.

Who knew that such a verdant secret flourished in these concrete confines? That’s apparently the conundrum that exercised Greta Mendez, a Trinidad-born dancer and choreographer, who begins her thoughtful peregrination with: “Sometimes I look into a place and I wonder.”

Her words stayed with me as I too looked and wondered at an exhibition highlighting the work of ten British African artists at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge.

These are unashamedly works that discuss the predicament of the country’s black population in terms of identity, exploitation and the lingering effects of colonialism, yet it is as if the exhibition curators are trying to obscure that worthwhile aim by naming the project Untitled: art on the conditions of our time.

As curator Paul Goodwin explains: “Instead of focussing on the blackness ahead of the works themselves Untitled flips this order and focusses on the works first and foremost. Questions of blackness, race and identity are shown to be entangled in the multitude of concerns – aesthetic, material and political – that viewers can encounter without the curatorial voice obscuring their works.”

But when it comes to focussing on the works, is this clever or a conceit? And is it consistent? Far from eschewing a curatorial voice, each contribution is accompanied by lengthy notes which are often notably prescriptive. Here’s just one describing the contribution of Barby Asante. Her “performative and discursive art practice addresses the politics of place, space, memory and the histories and legacies of colonialism”.

And another – by Larry Achiampong and David Blandy – is “revealed to be underpinned by a capitalistic structure and subject to the same systemic racism that is present in reality.” No equivocation here.

So to argue that the encounter with the works should not be reduced solely to an exploration of Black British identity is subverted by the very interpretations offered to the viewer. Perhaps, in the spirit of the project, they should have been left unexplained to allow the viewers the freedom to make their own interpretation.

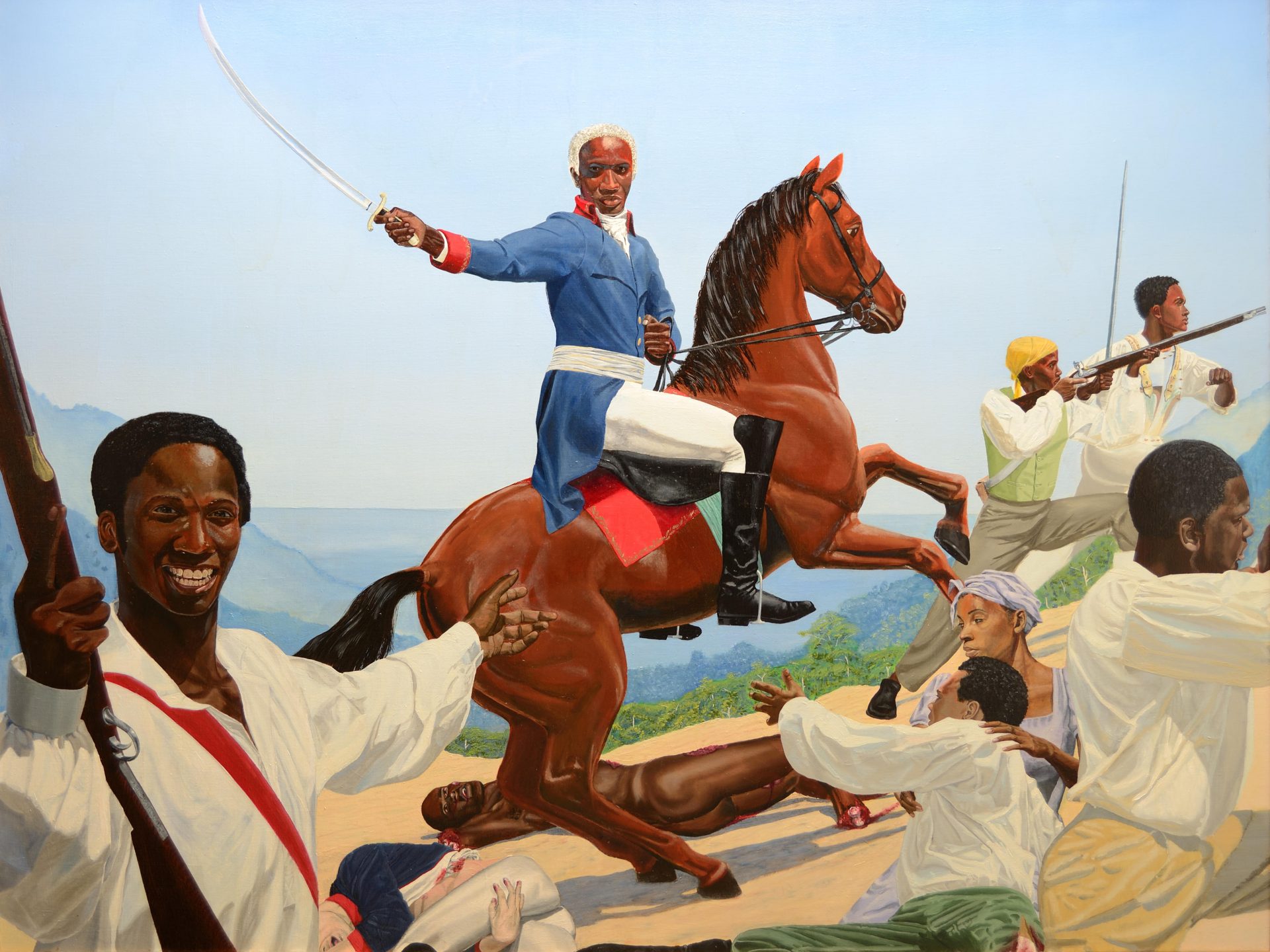

Any uncertainty as to the theme of the exhibition is immediately despatched with the paintings by Kimathi Donkor which greet the visitor in the first gallery. A striking image of the 18th century black freedom fighter, Touissant L’Ouverture at Bedourette, is a reworking of Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps which depicts the legendary Haitian revolutionary Touissant driving out the island’s French masters.

Donkor, who is of Ghanaian, Anglo-Jewish and Jamaican family heritage, and as a child lived in rural Zambia and the English west country, is known for his bracing views on race and colonialism, also offers the moving Nanny of the Maroon’s Fifth Act of Mercy which references a portrait by Joshua Reynolds painted in 1778 of one Jane Fleming whose family owned slaves in Jamaica.

More complex is a trio of videos by friends and collaborators Larry Achiampong and David Blandy, Finding Fanon, Part One, Part Two, Part Three. Inspired by the plays of Frantz Fanon (1925-1961) a psychiatrist and political philosopher from the former French colony of Martinique, his works explore the psychological impact of colonialism and post-colonialism. Achiampong is perhaps best known for his appearances in public wearing a round, black ‘golliwog’ head with crimson lips over his own head, while Blandy is best known for film using hip hop and soul, computer games and manga for inspiration.

Finding Fanon is shown on several screens set on a carefully chaotic set of branches, wires, rusty milk crates, bits of old TV sets, and is a thoughtful piece with the two creators often appearing as avatars of themselves wandering ‘in search of tomorrow’s dreams’ along seashores, dystopian cities and empty countryside. A voiceover intones their concerns about race and colonialism, war and the oppressive role of capitalism in a provocative way that never becomes hectoring. It is quietly, but forcibly, pessimistic.

A new work by Barby Asante is altogether more intimate. To make love is to create and recreate ourselves over and over again – a soliloquy to heart break is inspired by black feminist writer Audre Lorde’s Poetry is not an issue (1934-1992). The work is presented on four screens on three floors and pursues the legacies of colonialism with deceptively charming scenes performed by women reciting the poems while performing everyday rituals such as washing hair, braiding it painstakingly and winding on a turban.

Asante has also made a small selection of paintings from the Kettle’s Yard collection which was accumulated between 1957 and 1973 by curator Jim Ede and his wife Helen. They bought a row of dilapidated terraced cottages which they incorporated into one and lined with their ever-growing collection of art. The contemporary gallery was added in 2018.

The contrast between the spare lines of the new space could hardly be of greater contrast to the domestic setting of the original. The furniture has been left as it was when the Edes lived there, the books, and above all, the works. Ede collected paintings, sculptures and ceramics by more than 100 artists – illustrious names such as the sculptors Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Constantin Brâncusi and Barbara Hepworth, painters Joan Miró, Ben and Winifred Nicholson, David Jones.

For Jim Ede, Kettle’s Yard was more than a place to store his art. He held tea parties every afternoon for students and eager art lovers, they talked, discussed and played music. He would often lend students a painting to help them in their studies. He wrote how he hoped further generations would find a home there – “a welcome, a refuge of peace and order, of the visual arts and of music.”

Asante’s selection which includes a painting by Sonia Delaunay (Untitled), a design by Barbara Hepworth and a painting by Kate Nicholson called Sea Nymph and another of a boat by Veronica Ryan, Territories. Asante explains her choice of the latter two because they “connect to water though immigration, through transatlantic slavery and the weather which brings us here”.

Would the art lovers gathering to take tea with Jim Ede have come to that conclusion? Probably not. Ede was no stranger to the more arcane art of his day, eager to acquire or admire the new and difficult but there is a language problem here. Contrast the prolixity of the Untitled notes which explains that the exhibition “traces an interest in performativity, social participation, immaterial conceptualism, multimedia work and ephemeral practices?” with the description by Ede of a 1927 painting by Miró called Tic Tic which he used to illustrate the importance of balance in a work. It is positively poetic in comparison.

“If I put my finger on the spot at the top right all the rest of the picture slid into the left-hand bottom corner. If I covered the one at the bottom horizontal lines appeared, and if somehow I could take out the tiny red spot in the middle everything flew to the edges.

“This gave me a much-needed chance to mention God and by saying if I had another name for God it would be balance, for with perfect balance all would be well.” (Once a week the yellow spot which is in the bottom left is celebrated by the placing of a lemon on a pewter plate beneath the painting).

Given his eclectic taste in the bold and new and his enthusiasm for sharing opinions, Ede would take Harold Offeh’s Covers Playlist in his stride. The artist copies the poses struck by black singers in the 1970s and 80s on their album sleeves – most strikingly balancing naked in his kitchen in the position made iconic by Grace Jones. His new film Down at the Twilight Zone is a raucous documentary of a night in the LGBT life of Toronto, Canada.

It’s a contrast to Greta’s enigmatic ramble around the hanging gardens of Barbican filmed by an artist who goes by the enigmatic soubriquet NT and to the engaging figurative charcoal drawings by Phoebe Boswell of fishermen in Zanzibar which illustrate her own experiences in a “contradictory cultural legacy rooted in colonial histories”.

He may well have been intrigued by the carefully scuffed wood prints by Cedar Lewisohn – Untitled (Red Woodprints, Lewisham series) – which reference youth culture and knife crime via works seen in museums, not least because there are few, if any wood prints in the Ede collection.

A man who relished conversation and debate, Ede might well have been challenged by Evan Ifekoya’s Ritual Without Belief. Described as “black queer algorithm” it consists of music by singer Sade, conversations – hard to decipher – poetry and “breathing meditations”. It’s quite an ask. It lasts for six hours, the entire time the gallery is open, and has nothing to distract the listener but “waves” of black and white on walls and floor, a ceiling of balloons and a photograph of a bodybuilder wearing a bra. At least there are foam rubber mattresses to rest on. If today’s exhibitors could sit down for tea with Jim Ede the odds are that they might agree on one of the most potent images of recent times – the vandalising of the mural of footballer Marcus Rashford in Manchester and the way the people rallied round to create their own tribute with messages of support, hearts and flowers. Art on the condition of our time indeed.

■ Untitled: art on the conditions of our time, Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, until October 3