Van Gogh’s last 70 days, spent in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise just outside Paris, are full of mystery, wonder and tragedy.

This short interlude before his death on 29 July 1890, was something of a false dawn, when Van Gogh and those around him believed him to be well on the road to recovery from the mental health crisis that had caused him to cut off his ear 18 months earlier, after which he was admitted to the asylum of SaintPaul-de-Mausole, in Provence, where he would remain for over a year.

If the intense drama of Van Gogh’s last two years has overwhelmed the details of his final months, the already rampant mythology surrounding the artist was fuelled further in 2011, when biographers Steven Naifah and Gregory White Smith claimed that Van Gogh had not taken his own life as had always been believed, but was murdered.

In a new book, Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers & the Artist’s Rise to Fame, investigative journalist and Van Gogh expert Martin Bailey looks in depth at the period leading up to the artist’s death. This, Bailey says, “turned out to be the most productive of his entire career: he painted at the furious rate of a picture a day during his 70 days.”

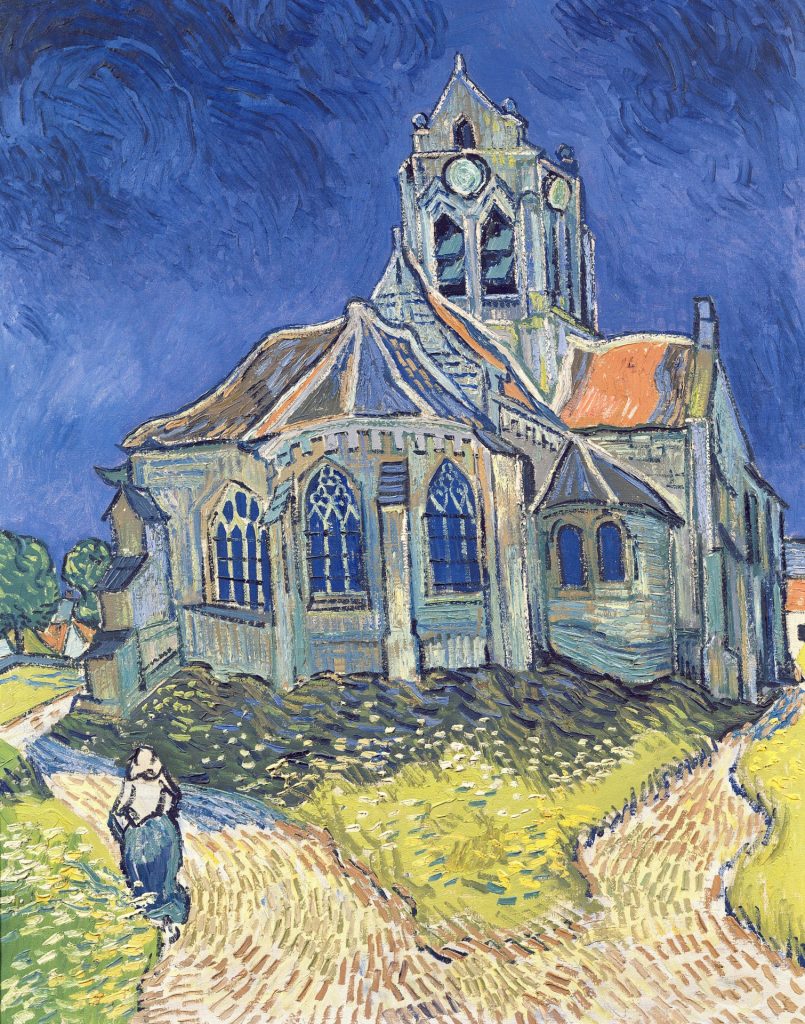

After the ecstatic, visionary canvases of Provence, the paintings made at Auvers are more subdued, and from the abstractions of the natural world, he created an expressionistic sort of realism.

Images.

Establishing the circumstances of Van Gogh’s death is principally a matter of dignity, but there are wider considerations, too. Usually understood to have been the consequence of years of mental distress, the manner of his death must affect the interpretation of his work and his posthumous reputation as a tragic hero-genius.

In this final instalment of his trilogy on the artist, Martin Bailey examines the circumstances of Van Gogh’s death in forensic detail, looks closely at his paintings from the weeks leading up to his shooting, and considers how Van Gogh’s posthumous reputation was forged.

Today, Auvers is a pilgrimage site, where you can visit his modest room at the Auberge Ravoux, furnished with a wooden chair with a woven seat, like the one in his famous still life, now in the National Gallery, London. From there you can visit the church, and the river, and the cemetery where he is buried next to Theo, his brother.

Theo was at his sibling’s bedside as he died, and he, and the doctors who attended him, were entirely convinced that Vincent had died by his own hand, having shot himself in a wheatfield on the edge of Auvers. Having missed his heart and with the bullet lodged in his chest, the artist struggled back to the Auberge Ravoux where he took to his bed, dying two days later on 29 July.

In 2011, two American writers unearthed an interview given in 1957 by René Secretan, who in 1890 had been a teenager, visiting Auvers with his brother Gaston. René claimed to have stolen the gun from Arthur Ravoux, using it to play cowboys and shoot squirrels. Naifeh and Smith argued that the brothers had shot Van Gogh accidentally, and that Van Gogh, who “welcomed death”, had protected the boys by claiming suicide in what they described as “a final act of martyrdom”.

Martin Bailey thought the theory deeply implausible, and he writes: “It must be extremely unusual, if not unprecedented, for a victim of a shooting by a casual acquaintance to claim that it was a failed suicide attempt”.

The evidence he needed to refute the claim emerged in 2019, when the gun came up for auction: “The most memorable moment in my quest to explore Vincent’s final days was holding the gun that had ended his life”.

Bailey subsequently discovered that the gun had been found in 1960 by a farmer, Claude Aubert, while ploughing a field near the chateau of Auvers. Over time, the gun had found its way into a drawer, where it remained until its sale.

The condition of the gun, and the circumstances of its discovery persuaded Bailey not only that this really was the gun that Van Gogh had used, but also that it had indeed been suicide. It was badly corroded, consistent with having been thrown aside rather than buried, and the safety trigger was unlocked “so it had probably been fired shortly before being abandoned.”

Bailey concludes: “If Secretan had short the artist, why would he have simply abandoned the weapon in an open field that was regularly ploughed? Had he wanted to hide the evidence, surely he would have buried it deeper or hidden it in dense vegetation.”

Treating art as autobiography is a dangerous business, but in Van Gogh’s case, Bailey tells me, “We’re so interested both in his art and his life, and probably fairly equally, and the two are so closely entwined, that it makes it more important to understand his personal life if one wants to get some depth to understanding his art.”

To this end, Van Gogh’s letters, of which 820 survive, nearly all written to his brother Theo, are a vital resource, in which he weaves details of his daily life, with philosophical musings, and discussions of his work. Bailey said: “We are really dependent on the letters which are absolutely marvellous: certainly, they colour the way we see his life, and because he writes about his paintings, they colour the way we see a particular work”.

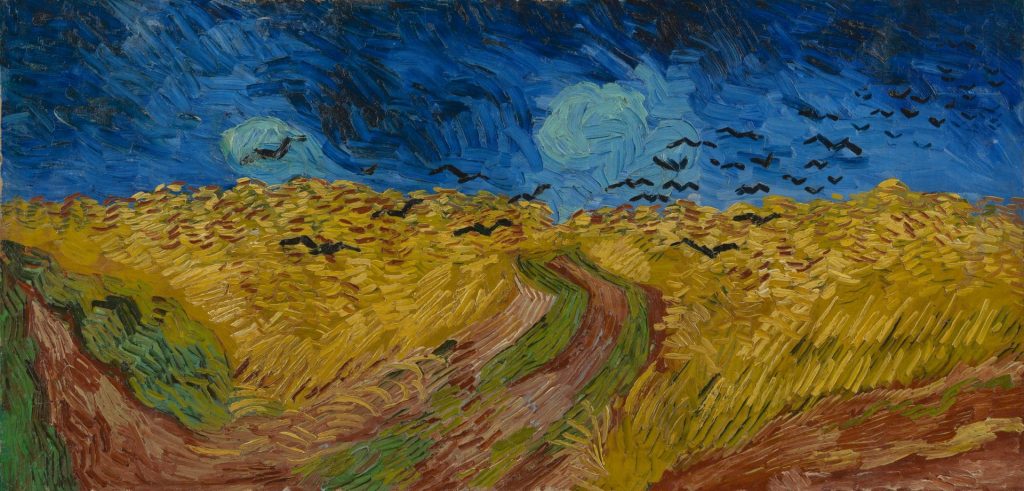

The letters make a connection between his work and his mental state, and one passage in particular has given a series of paintings of wheatfields particular resonance, especially Wheatfield with Crows, which was long thought to be his final work. In a letter to Theo and his wife Jo, dated 10 July 1890, he wrote: “they’re immense stretches of wheatfields under turbulent skies, and I made a point of trying to express sadness, extreme loneliness”.

However, as Bailey points out, the letter takes a more positive turn in the same paragraph, indicating the invigorating effect the freedom of the countryside had on him after his confinement in the asylum, and the importance he placed on painting as a way of managing his condition: “I hope to bring them to you in Paris as soon as possible since I’d almost believe that these canvases will tell you what I can’t say in words, what I consider healthy and fortifying about the countryside.”

Van Gogh arrived in Auvers-surOise on 20 May, just four days after leaving the asylum. It had been agreed that here he could live freely, but under the watchful eye of Dr Gachet, of whom Bailey writes: “I became increasingly convinced of the importance of the role played by Dr Paul Gachet, a physician, artist and collector.”

Van Gogh was not immediately impressed with the doctor, writing, though never sending, a letter to his brother: “We must IN NO WAY count on Dr Gachet. In the first place he’s iller than I”. Very quickly though they became friends, and Van Gogh welcomed the doctor’s advice to “Work a great deal, boldly, and not think at all about what I’ve had.” The extent to which Dr Gachet saw himself as responsible for Van Gogh is an important question for Bailey, who said: “I don’t think he could have done anything more in the way of treatment. The only thing one can question is the extent to which Dr Gachet saw himself as responsible for Vincent’s medical and psychological state, and it’s a bit unclear whether he’d taken on that responsibility. I think he thought he was there to keep a friendly eye on him rather than to be a doctor.”

As to the question of murder, or suicide, Dr Gachet’s role at Van Gogh’s deathbed is surely decisive, and Bailey is certain that he would have removed the bullet from Van Gogh’s body shortly after his death, at which point it would have been clear to him if it had been fired from a distance. Bailey’s research into Dr Gachet revealed various left-field and macabre interests including his membership of the Society for Mutual Autopsy.

For this reason, he argues: “The doctor’s membership of the society and his experience of undertaking autopsies means that by this time he would not have felt squeamish about opening up the chest to remove the bullet, not even on the corpse of a friend.”

Though Van Gogh sold only one painting in his lifetime, by the early 20th century his reputation had grown considerably. Theo died of syphilis six months after his brother, and it was his widow, Jo, who did most to ensure Vincent’s fame, helping to organise exhibitions, and selling and lending works. It was only in 1914 that she published his correspondence with Theo, having realised with considerable perspicacity that to do so earlier would risk obscuring his work with the sensational details of his life.

Despite Jo’s best efforts, Van Gogh’s life has often attracted unduly voyeuristic interest, with countless films, books and “immersive experiences” exploiting and sensationalising his suffering. To this, Bailey’s sound research and sensitive insights are a necessary antidote, and by dispensing with the theory of Van Gogh’s murder, he has perhaps at last offered the artist’s restless ghost some peace.

Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers & The Artist’s Rise to Fame by Martin Bailey, published by Francis Lincoln, £25 hardback