A new cafe has opened on the corner of The Strand and Surrey Street, just off the Aldwych, in London. Nothing particularly interesting about that. Except this one, although it serves real coffees, croissants and croque monsieurs, is fictitious.

It’s Le Sans Blague cafe, a set from Wes Anderson’s new film The French Dispatch, now brought to life as part of an exhibition of the original sets, props, costumes and artwork that throws light on the director’s unique attention to detail and the meticulous aesthetic of his cinematic universe.

Everything in The French Dispatch exhibition has been brought over from the movie shoot, including Bill Murray’s brown suit, Tilda Swinton’s gown, Adrien Brody’s art dealer calling cards and Owen Wilson’s pushbike – even the huge paintings created by tortured genius Rosenthaler, played by Benicio del Toro, are aligned along one vast wall.

French Dispatch. Photo: Searchlight Pictures

While the music of Alexandre Desplat’s score tinkles in the background, visitors can wander into the film’s various rooms and feel the way the star cast must have felt as they inhabited the fictive world imagined by Anderson for his homage to American foreign correspondents who sent back their ex-pat tales from this exotic land of baguettes, sewers, genius chefs, student protests, cafes, gendarmes, artists and artisans.

“Every single detail counts,” explains curator Kevin Timon-Hill as he takes me through the show. “Every pattern, every curtain and carpet, every typeface and business card all have a clear through-line of thought from Wes that’s passed down to the creative team and everything has a purpose, like it would in an animation – you lift that thinking and put in into a film and you get The French Dispatch.”

The exhibition, set in the huge space of 180 Studios, allows the visitor to practically walk through the storyline of the film, from the establishing shots and sets of the fictional town Ennui-Sur-Blasé, where the bus maps and city streets are outlined, where posters adorn the walls and kiosks burst with magazines and the latest editions of the newspapers.

Then, we’re into the newspaper office of The French Dispatch itself. “Bill Murray actually sat at this desk, leant on it, wrote on it,” says Timon-Hill. And there’s Murray’s suit for the character of Arthur Howitzer, patrician editor of the titular magazine, hanging beside the desk, behind which a backdrop from the set gives the impression of Ennui stretching out into the crepuscular distance. A still from the film is on the wall to show just how exactly the scene at the exhibition is replicated on the big screen.

Timon-Hill was art director on the movie and spent seven weeks working in Paris on the drawings before moving down with the production team for five months in Angouleme, taking over factories and warehouses to create the fictive world. “We were in a disused felt factory, in an old naval shipyard but also Angouleme was a key town in the production of print and paper, so there are lots of large factory spaces we could work in and Wes world really descended on the place.”

There’s a saying in movies, often used by actors or directors to modestly deflect praise from their own work and share credit among the rest of the cast and crew: it takes a town, they say. “Well, in this case, it certainly did,” remarks Timon-Hill.

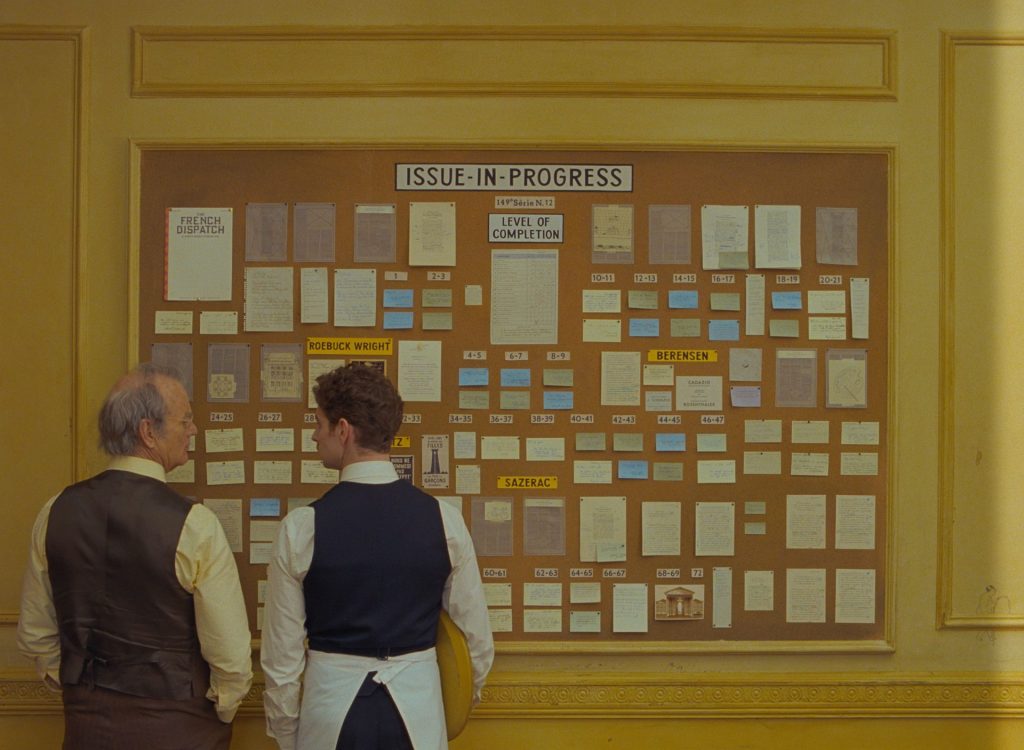

One is struck by the level of detail. Little notebooks have doodles and annotations; sheets of typed copy have corrections and scribblings. These are Howitzer’s edits, but drawn and written in advance by the art department.

“We decide what the character’s penmanship would be like and assign an artist to do it – the sets and props reveal so much about the character, they’re part of the creation,” he explains. “The actors really appreciate the details – if they’re opening a drawer, they like it to be stuffed with pencils and papers belonging to their character.”

We pass by Frances McDormand’s outfit and Jeffrey Wright’s suit and see them wearing the clothes in another shot from the film. Here’s Owen Wilson’s character’s bike and some vintage typewriters sourced from various flea markets.

“Everything was kept, wrapped in cling film, put a palette and taken to storage, like little curiosities,’ remarks Kevin. “There was always a sense that the props would have an afterlife and not just be used for the one shot they appear in – sometimes these things are on screen for a split second but each detail has to be exact for Wes to allow it on camera. On screen, you blink and you miss it but here you can pore over the details and that adds a new dimension to the film experience.”

For Anderson aficionados, the ability to engage with the director’s aesthetic and playful visual style is precious. I look for grammatical errors in the French posters and on the newspapers – reader, I find none – and I wonder if these are real news stories taken from old sources.

There’s a story, for instance, on one front page about a herring fisherman called Jean Oberley. “Many of the names are taken from our crew because they are cleared for usage – so Jean Oberley could well be a carpenter or a driver that we used – these are the little ‘easter eggs’ you have to look out for in Wes’ work.”

Watching the movie itself, I did ask myself several times if it’s all worth this level of design and beautiful detail. For me, the four or five different stories told in the series of chapters that make up the movie don’t always add up, although every shot is without doubt masterfully composed and bursting with ideas.

However, artist Sandro Kopp, whose paintings are aligned along a huge wall in the next stage of the exhibition is certain of the overall vision. “It’s about the necessary steps for creativity and the absolute conviction that art matters,” he says.

Kopp’s work ‘plays’ the character of Benicio del Toro’s Rosenthaler’s paintings, if you get what I can possibly mean. Kopp does the masterpieces we see in the movie and they are huge, three storey-high abstracts with thick daubs of swirling impasto.

“I must have done 47 versions of them to get them right for Wes,” he tells me over zoom from New York, having just come from a talk at MOMA about it. “First it was about getting the abstract concept of flesh, then about the size, then about how they would look in the light, then we’d set them on fire, attack it with a knife.”

So, even the painters get meticulous direction on a Wes Anderson set. “But that’s because it’s important in a film that’s about creative crisis to get the creativity right, and Wes needs the viewer to feel that,” says Kopp.

“It’s a very profound method, I think. It’s why I was there for three months, painting in a sealed-off part of the Felt Factory, with huge heaters blasting away to get the paintings dry – not always successfully. In the scene where the masterpieces are revealed, one of them is still totally wet because Wes made me go back and change the top half of it just before he rolled camera.”

According to Kopp, you need four or five viewings to even remotely appreciate the meaning. “It’s like concentrated cordial, just too much to take in at first, you have to dilute it with viewings or your eyes will be distracted by details, by the dogs in the corner or the clothes, or the mice drawn on the walls. I can’t think of another film-maker who is so adhered to the idea of art and artistry and how every little thing should be considered. It’s a very special approach.”

Another impressive section of the exhibition is the recreation of the police commissariat, with its perfect reconstruction taken from old French films noirs, the old telephones and radio equipment, the road maps on the wall. The miniatures on display show matte models of the town of Ennui, as well as models such as a aeroplane in cross section and there’s room showing the music video to the song Aline, made by Jarvis Cocker’s fictive French popster Tip Top, and playing his album of chansons specially covered and recorded to support the film’s release, featuring songs originally by Gainsbourg and Francoise Hardy.

And then there’s the Sans Blague itself – exit through the coffee shop, now open to the public and featuring the original spiral staircase and part of the original zinc bar, plus some chairs and tables and ashtrays from the set. The coffees and pastries, I’m assured, are fresh.

“We wanted the public to get the feeling they were in a Wes Anderson film,” says Timon-Hill over a noisette in the Sans Blague. “But actually, it’s become more immersive than that – I think the final experience is more like how the actors feel being on set.

“Building it here in London, we would have scenes from the film and we’d freeze-frame them to make adjustments to make sure we were being accurate.”

Visiting the exhibition has given me more appreciation of the care and the craft, and the coffee. It’s a world of curiosities, for sure. I can’t help feeling that the film is caught between homage and pastiche and can’t always shake the inertia of its own beauty, hampered by an inability to be anything but a delicate tableaux, to build up narratives that hold the attention and augment any artistic message. The twee nature of some of the French cliches have, to me at least, come over as a kind of cultural misappropriation, a cutesification of real lives viewed through a lens of patronising imperialism

But seeing it, being part of it, does imbue some real feeling, and you get an appreciation for the intelligence and emotional work that’s gone into the reproduction, the absolute respect for the culture the French Dispatch is writing about and which its indulged authors are chronicling for a culture-starved audience back home in Kansas.

See it for yourselves – probably best after first seeing the movie. If you don’t like it, you can always just sit in Le Sans Blague and try the onion soup.

The French Dispatch exhibition is on at 180 Studios Oct 14- November 14. The film is on UK cinemas from October 22