The French elections, still six months away, are shaping up to be the nastiest since the 1930s. Then, the contending forces were a vaguely internationalist left against a bourgeois-nationalist or fascist-fellow-travelling right.

The April 2022 elections are boiling down into a confrontation between the centrist-Europeanist Emmanuel Macron and the identitarian far right. So far so predictable – except that the silver-tongued, racist pundit Eric Zemmour – profiled in these pages recently – is replacing Marine Le Pen as the Great White Hope of the Kremlin and lots of other people who should know better.

An obvious question arises. What on earth has happened to the French left, which was in power until four years ago? Have they divided and sub-divided themselves into irrelevance? Oui/non, as they say in Normandy. As things stand, left and green politicians will play only a minor part in the first round of the elections on April 10. They will play no part in the two-candidate run-off two weeks later. Not so left wing voters. It is they who will ultimately decide the identity of the next president of the Republic.

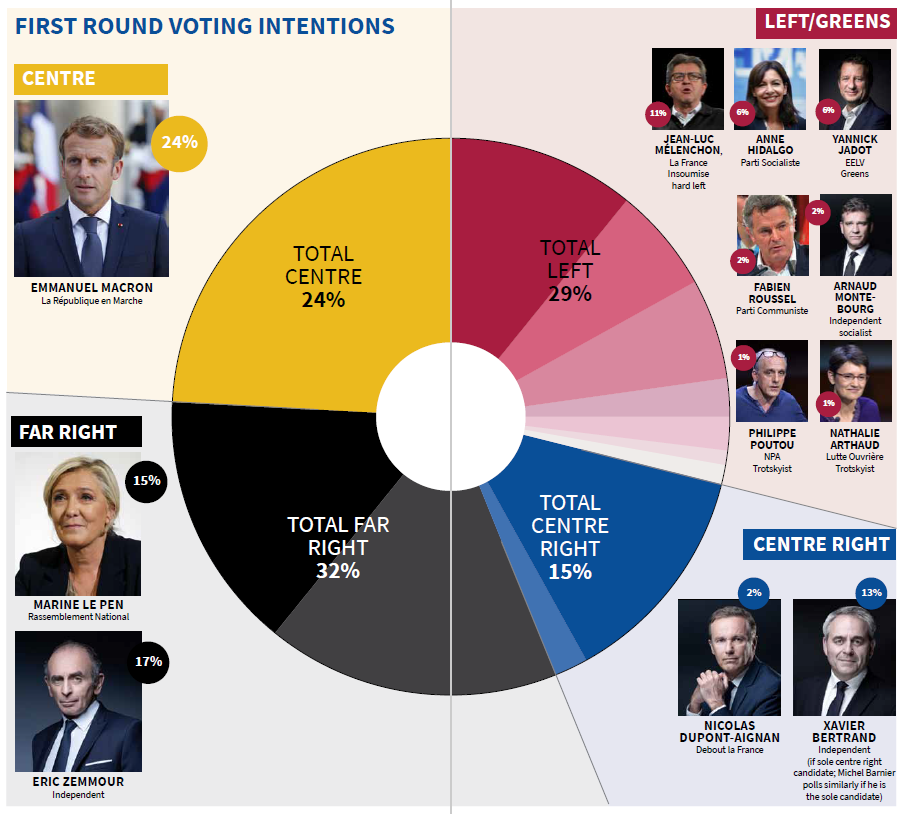

This is one of two paradoxes at the heart of a fascinating and troubling election campaign. Left/green voters – reduced to roughly 30% of the electorate – have split into seven different camps, including three kinds of socialist and two flavours of Trotskyists. All left wing contenders are falling far short of the scores needed to make the two-candidate run-off on April 24.

As a result, left wing voters may well face a straight choice in Round Two between a man they love to detest (president Macron) and a movement they loathe (xenophobic, Muslim-baiting nationalism).

Voters on the harder left say that, in that event, they will abstain or spoil their ballots.

Experience suggests that many of them will finally vote for Macron, pince-à-linges (clothes-pegs) on noses. Either way, a splintered, angry left holds the key to an election that will have profound consequences – and not just for France. The meteoric rise of Zemmour in the opinion polls – from 5% to 17% of first-round voting intentions in six weeks – could yet be followed by a meteoric descent.

More likely, he is here to stay. Zemmour, 63, anti-Muslim, anti-feminist, anti-gay, anti-European, twice convicted of provoking racial hatred, has skilfully occupied a double vacuum on the French far right and centre-right. He has the advantage of populists through the ages: he exploits the contradictions and evasions of mainstream politicians while evading recrimination – so far – for his own. (See also, Trump, Johnson).

Zemmour has exposed Marine Le Pen’s weaknesses, as she struggles to make her father’s xenophobic party both radical and respectable. He has benefited from the ideological divisions, personal quarrels and absence of a single, convincing voice on the ‘mainstream’ right – the dysfunctional political ‘family’ of de Gaulle, Chirac and Sarkozy.

Zemmour has yet to say how he can turn his backward-looking – and backwards – ideas into a programme for government. How can you be both an admirer of de Gaulle and a weaselly defender of the pro-Nazi Vichy regime? How can you demand that France’s five million Muslims assimilate and adopt Christian names without provoking the civil war that Zemmour says that he wants to avoid? Despite these contradictions, some people on the centre right who shunned Le Pen are ready – for now – to swallow Zemmour’s intellectualised nouveau fascism. With five months until the campaign officially begins, France has split into four voting blocs: The left/greens have 30% divided eight ways. The far right has 30%, divided two ways. The centre right has 15% but will not decide on a single candidate until December. Macron has around 25%. For now, he looks relatively strong. His approval ratings – ranging from 35 to 43%, depending on the polling organisation – are the highest for a late-term president for 20 years.

Economic growth this year is surpassing expectations at 6.25%; unemployment will fall by the year’s end to 7.6%, the lowest in 13 years.

But recent French political history is against him. France has not given a president second term since 2002. It has not directly rolled over the government in power since 1978.

Mitterrand and Chirac were only re-elected after losing mid-term parliamentary elections and having to play second fiddle to PMs from opposing parties.

The rise of Zemmour is double-edged for Macron. It imposes themes on which Macron is weak or uncomfortable – immigration, security, national identity. It steers debate away from the themes that he favours – France’s Covid recovery, its high rate of vaccination and strong economy. On the other hand – here is the second big paradox – Zemmour’s rise could ensure that Macron wins a second term.

The president’s greatest fear was always to be matched in the second round against a convincing candidate from the centre right. If that happened, the disgruntled left would vote anti-Macron with a clear conscience

Zemmour’s success has exposed Le Pen’s weakness. It has also blocked, for now, the hopes of a weakened and quarrelsome centre-right. The president of the northern France region Xavier Bertrand has been running an independent campaign since March. He started at 16% and rose to 18%.

Zemmour has pushed him back to 13%-16%. Bertrand, competent but uninspiring, still insists that he is the man who can defeat Macron and Zemmour. He has finally agreed to submit to a closed primary on December 4.

The electorate is the 80,000 members of the main centre right party, Les Républicains (which Bertrand once led but left in 2017). The favourite to win this party vote is now former Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier – who is much less popular than Bertrand with the wider public. In any case December is a long way away.

Can they build some momentum at last? The best hope of the ‘mainstream’ right is that Zemmour deflates a bit – but not too much.

Zemmour and Le Pen might then cancel each other out, allowing a single centre right candidate to seize the golden ticket into Round Two.

Can Macron buck recent French political history and win re-election, despite a term of office troubled by incomplete economic reforms and multiple crises (from the Yellow Vests to Covid)? Yes. But he needs the unwilling help of left wing voters who detest him and the accidental ‘support’ of a blundering, divided centre right. If he faces Le Pen in the second round again, he will win – though probably by less than his 66-34 landslide in 2017.

Faced with a choice between Macron and Zemmour, there will be many abstentions and blank votes but not enough for Zemmour to win. The thinking part of the centre right and much of the left will go with Macron. In all these machinations and manoeuvres, the French left will play little part. And yet they – grumbling and spluttering – will have the casting vote.

BACK TO THE THIRTIES?

French politics became increasingly splintered and vicious throughout the 1930s as the Third Republic headed towards its eventual collapse in 1940.

The Great Depression had hit the country slightly later than others – and had a deeper impact than in many countries.

In 1934, far right riots in Paris raised fears of a coup d’etat and set the tone for the rest of the decade, with leftists pitched against bourgeois-nationalists in an increasingly bitter struggle which weakened the state – then, a parliamentary democracy – and hastened its later implosion.

Warning: Illegal string offset 'link_id' in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 357

Notice: Trying to get property 'link_id' of non-object in /mnt/storage/stage/www/wp-includes/bookmark.php on line 37